Travelling the Tibetan and Mongolian Borders in 1923 - Part 4 Sichuan and Gansu

Finding the way through dialogue and cultural exchange

Part 4

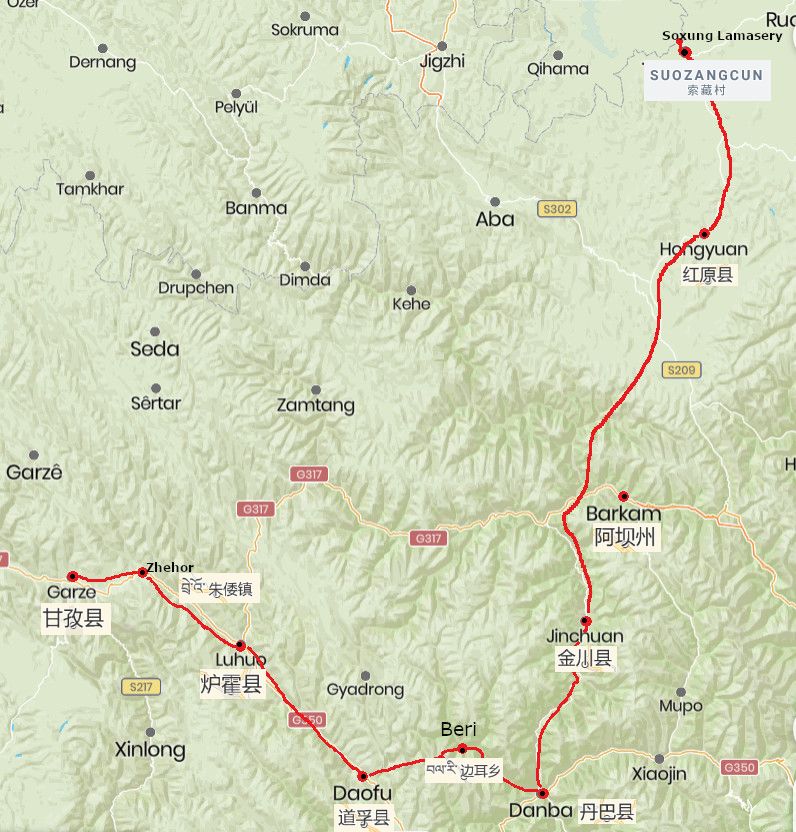

The fourth section of the journey was from Kanze (Kandze) to Sotsong Gomba, - thirty-five stages. A total distance of about 460 miles.

Click on the map above to show the route from Kanze to Sotsang Gomba on a 1923 map

Click on the map above to show the route from Kanze to Sotsang Gomba on a 1923 map

Route Map with current place names from Kanze and Soxung Gomba

Route Map with current place names from Kanze and Soxung Gomba

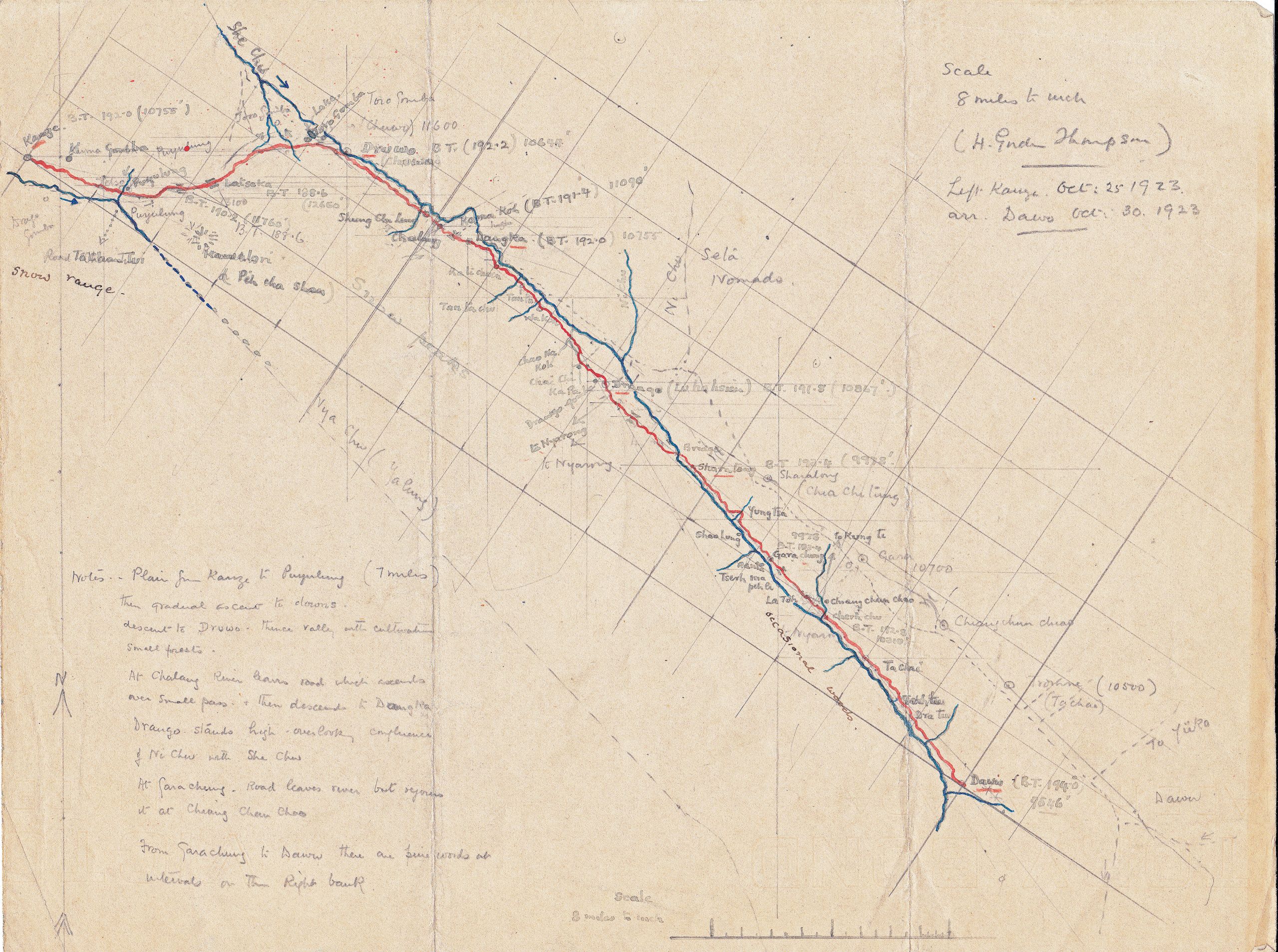

Hand-drawn map of the first section of the route from Kanze to Dawu

Hand-drawn map of the first section of the route from Kanze to Dawu

Day one hundred October 25th 1923 Kanze to Driwo - 27¾ miles

“Left Kanze at 9.35 after a lot of trouble with the man who had been engaged as our guide to old Taochow. Eventually we got fixed up with one of his partners - also an old Taochow man, but the delay made our arrival at Driwo after dark. I took a photo of the place where Pereira lies, with Kanze in the background, and bade farewell to this good friend”.

The little cemetery under the shadow of the Lamasery at Kanze - grave marked with a cross

The little cemetery under the shadow of the Lamasery at Kanze - grave marked with a cross

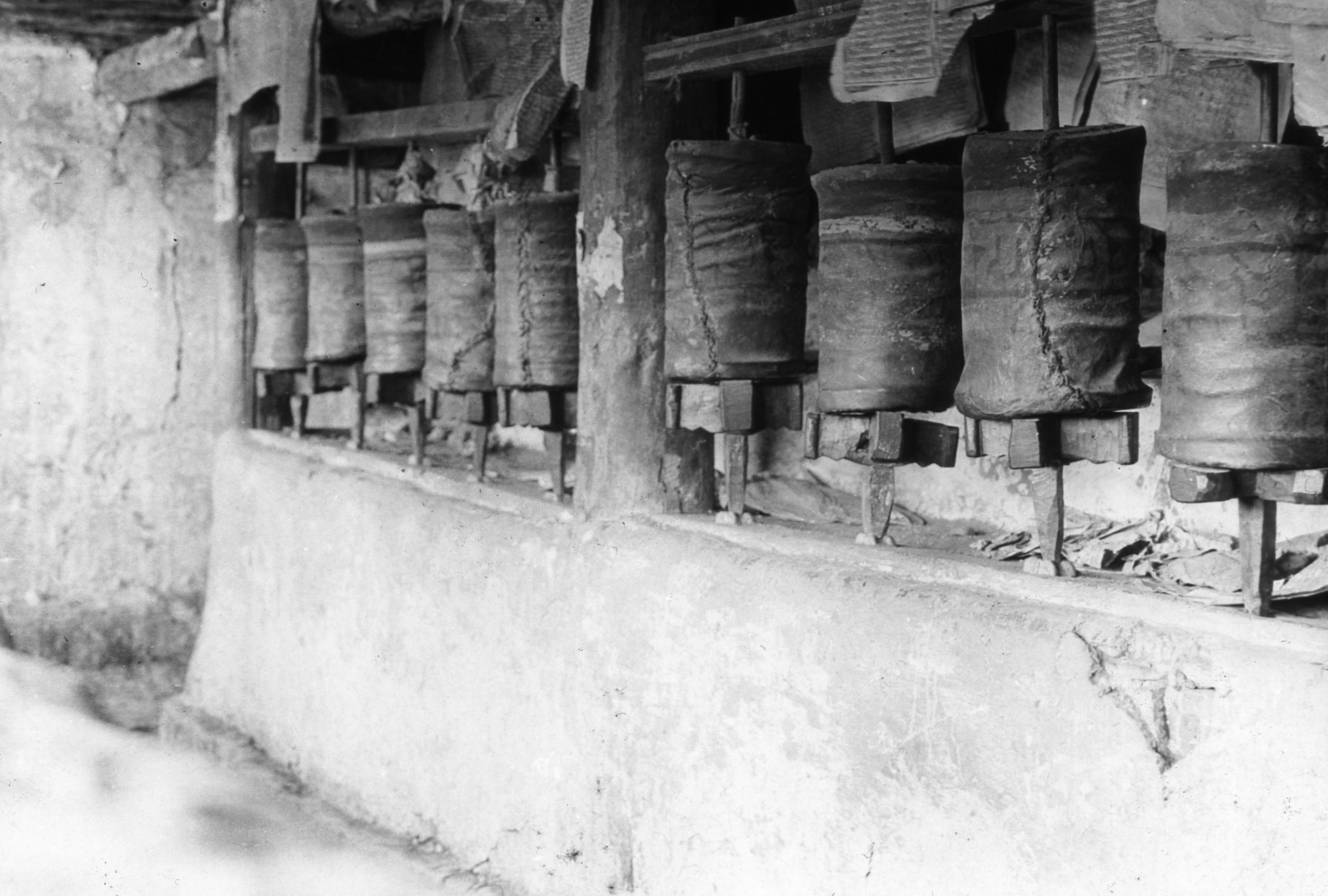

“Initially we travelled for seven miles across a plain, and then climbed once more into the hills. On the way we passed another Chorten with a row of prayer wheels which made for a good photo”.

Prayer wheels in a chorten just outside Kanze

Prayer wheels in a chorten just outside Kanze

“Had some snow and it is very cold. In trying to put on my coat whilst on the mule that I was riding, the mule became frightened, and backed up - the bridle came off and I went over his head. However, I am none the worse. We stopped for half an hour for something to eat, then moved on again. We are now travelling with mules and changing the animals every day”.

“Once more on the road. It seems strange to be alone, but my time is fully occupied, for in addition to seeing patients when we stop for a rest, I am also kept busy making a prismatic compass traverse of the route, getting the altitudes, and trying to keep a photographic record”.

They passed a lamasery called Tora Gomba just as dark was falling, but pushed on. HGT was ahead of the mules with their soldier who said it was not far to Driwo, and soon the moon came out and they could begin to see their way.

They arrived in Driwo (10,644 ft.) at about 6 p.m. and their loads half an hour later. At first, they had some difficulty in finding a house to stay at as the soldiers’ barracks were said to be full up though HGT thought there was really plenty of room.

In his journal HGT wrote:

“Pudala gave the headman a good few lashes with his whip, until I got it away from him and warned him that for a repetition of such conduct I would dismiss him on the spot, and he could find his own way home”.

"At last we got fixed up in a nice Tibetan house, quite clean, and after some eggs got to bed. Dead tired after all the anxieties of Kanze and then a trying day”.

Day 101 October 26th, 1923 Driwo to Dangka - 12 miles

“We left Driwo, where there was an old chieftain castle and a good Chinese cantilever bridge, at 7.25 and I decided only to do a half stage as it had been such a trying time over the last 10 days”.

Old chieftain castle and a good Chinese cantilever bridge at Driwo

Old chieftain castle and a good Chinese cantilever bridge at Driwo

The road followed the valley of the She Chiu River until near to Dangka, the river made a bend to the East near Chalong where they stopped for lunch.

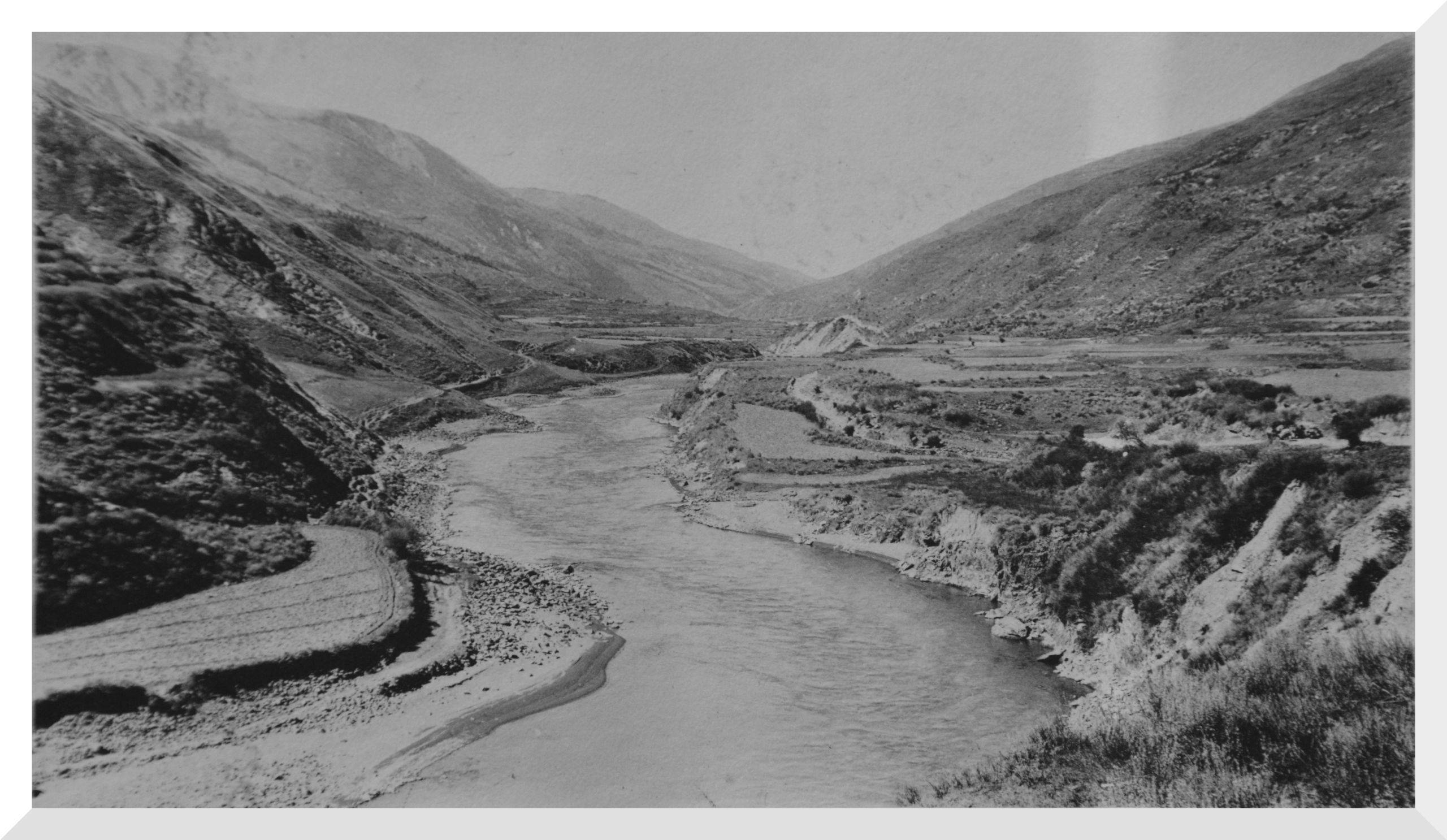

View up the She Chiu river valley from Driwo

View up the She Chiu river valley from Driwo

“A little further on we came to a rise called Kama Koh (11,070 ft.) and then descended steadily for a mile to Dangka (10,755 ft.), arriving at 1.27 where we were met by a group of farmers, by the look of them. I continued with the mapping that Pereira had been doing, finishing at about 4 p.m. This short stage has quite rested us, and after another short stage we shall all feel A 1.”

Day 102 October 27th, 1923 Dangka to Lu Ho Hsien - 15 miles

“After a good sleep, I am feeling quite fit again. We left at 7.37 a.m. and followed the She Chiu river all day - a very pretty river with bright blue water. The valley was a good open one with hills on each side, backed by mountains covered with snow, of which we got a glimpse when there were side valleys. At 10.30 we passed through a small village called Wa Koh- where there was a post of 30 soldiers”.

View up the Sha Chiu valley from near Wa Koh

View up the Sha Chiu valley from near Wa Koh

"It seems to be a very busy road, and we passed numerous yak with loads, and also odd soldiers. There are more Chinese in comparison to Tibetan than generally. At 11.10 we slowly left the river which was separated from the road by low hills, and did not see it again till we were nearing Lu Ho Hsien (10,867 ft.) at 1.15”.

“Yesterday there were great flocks of wild pigeons, and as the Chinese boy had learnt how to use the shot gun, he shot 4, bringing down 3 with one cartridge. Today we saw some yellow wild duck, and also a small wild bird - something like a snipe, but larger - they are called Hu-hz - the boy shot 3”.

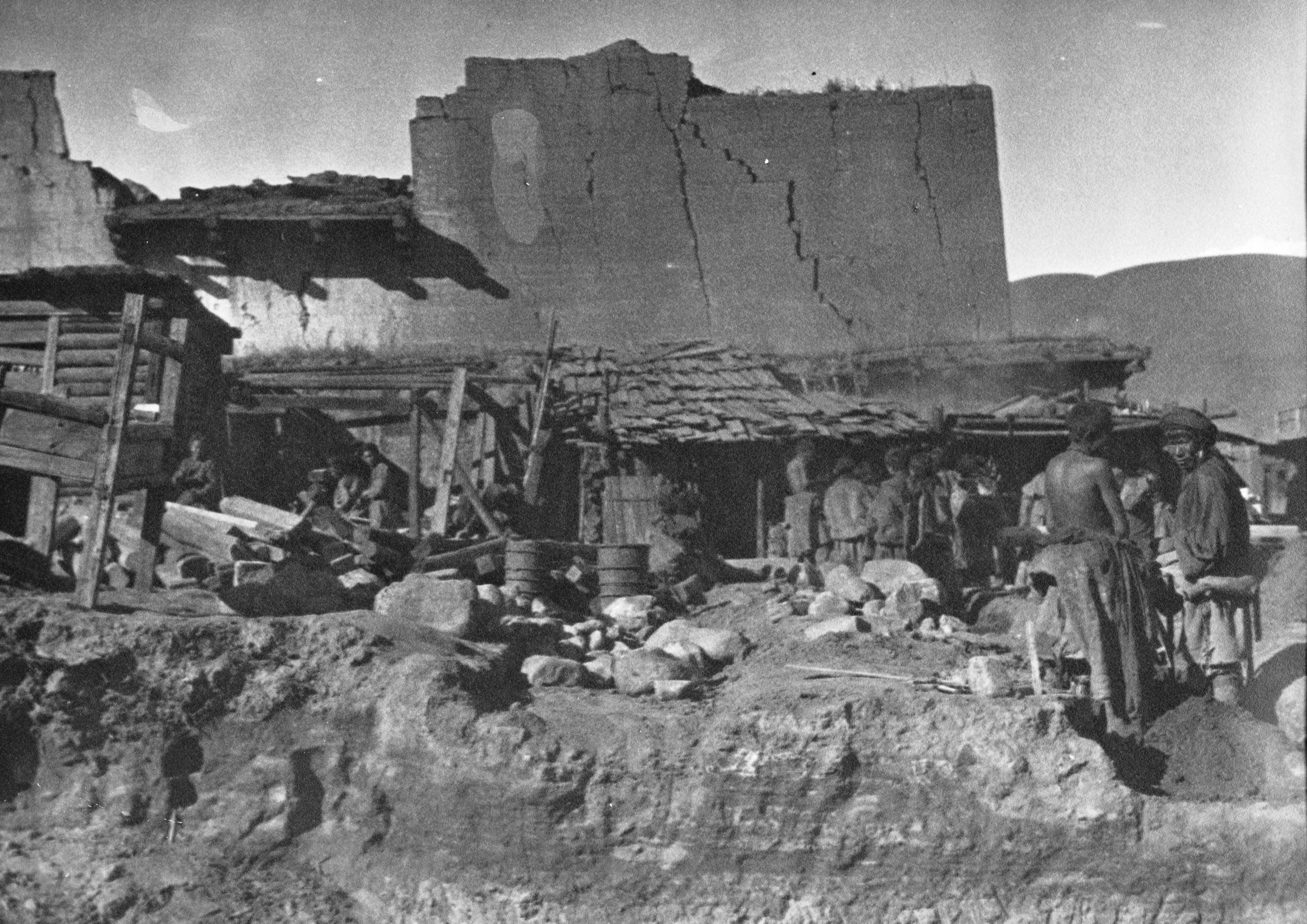

Results of 1923 earthquake at Lu Ho Hsien

Results of 1923 earthquake at Lu Ho Hsien

They arrived at Lu Ho Hsien (Drango in Tibetan), where in February 1923 - on the 28th of the 2nd moon they had a bad earthquake.

Lu-ho-hsien after earthquake Feb 1923

Lu-ho-hsien after earthquake Feb 1923

“The nearby town of Sharatong was also practically wiped out, and between the two places, they say 2,000 to 3,000 people were killed. We noticed a man ploughing with only one ox, his other ox had been killed by the earthquake. At Sharatong the French priest lost his life, and their mission was destroyed”.

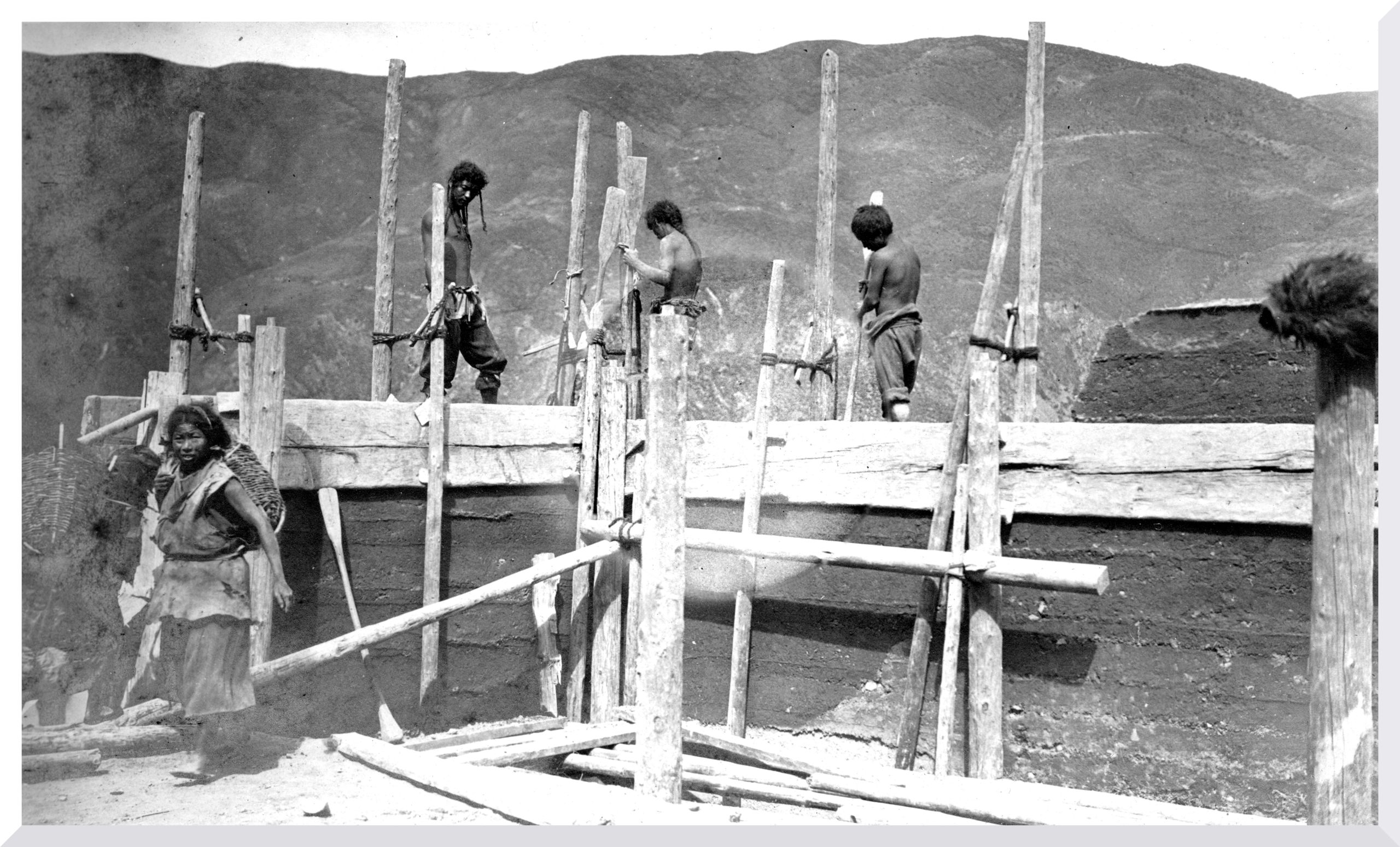

Tibetans re-building houses

Tibetans re-building houses

“It must have been a bad quake, for most of the houses here are in ruins. However, building is going on apace and all round can be heard the sawing of wood and hammering of timber. Meanwhile many of the people are living in tents”.

Day 103 October 28th, 1923 Lu Ho Hsien to Sharatong - 10½ miles

“We had great difficulty with the mules today - when we were all ready to start the animals were not forthcoming. The reason given was that the earthquake had destroyed such a lot, including yak and ponies, that it was difficult to find enough for the work, let alone for transport. At last four ponies and two miserable looking yaks turned up”.

“At 9.55 I informed the Yamen that I was about to start, so they sent a soldier round and leaving the boys with the baggage I started with the soldier and our new guide (Ah Hong) who had been engaged at Kanze".

Soldier escorts from Lu-Lo-Hsien. One Tibetan and one Chinese

Soldier escorts from Lu-Lo-Hsien. One Tibetan and one Chinese

“I aim to reach Sharatong - only about 10 miles away - to see the French RC Father and arrange with him for a stone to be obtained for GP’s grave at Kanze. I am loath to leave the baggage because the road to Ta- chien lu is often troubled with robbers, called Chagba, - but I feel I have to risk it.

“There was a slight climb and then a long descent - the road slowly approaching the river again, which it had left before Lu Ho Hsien. At last we got down to river level and came to the bridge built by the Catholic mission - a fine cantilever wooden bridge - now a wreck, caused by the earthquake on March 24th 1923”.

Bridge at Sharatong after the earthquake

Bridge at Sharatong after the earthquake

“We climbed over the wreckage of the bridge and after another mile we reached Sharatong (9,978 ft.), a small village, but the most advanced part of the R.C. mission to Tibet. They had a good compound and about 80 mû (about 5 hectares) of land beside, but the village had been absolutely levelled to the ground, the Church and Mission House a mass of ruins”.

Roman Catholic mission at Sharatong after the earthquake of 1923

Roman Catholic mission at Sharatong after the earthquake of 1923

“The French priest, Père Abue, had been killed with 12 others when his house fell, and his grave was in the corner of the compound. The whole place is in a pitiful condition”.

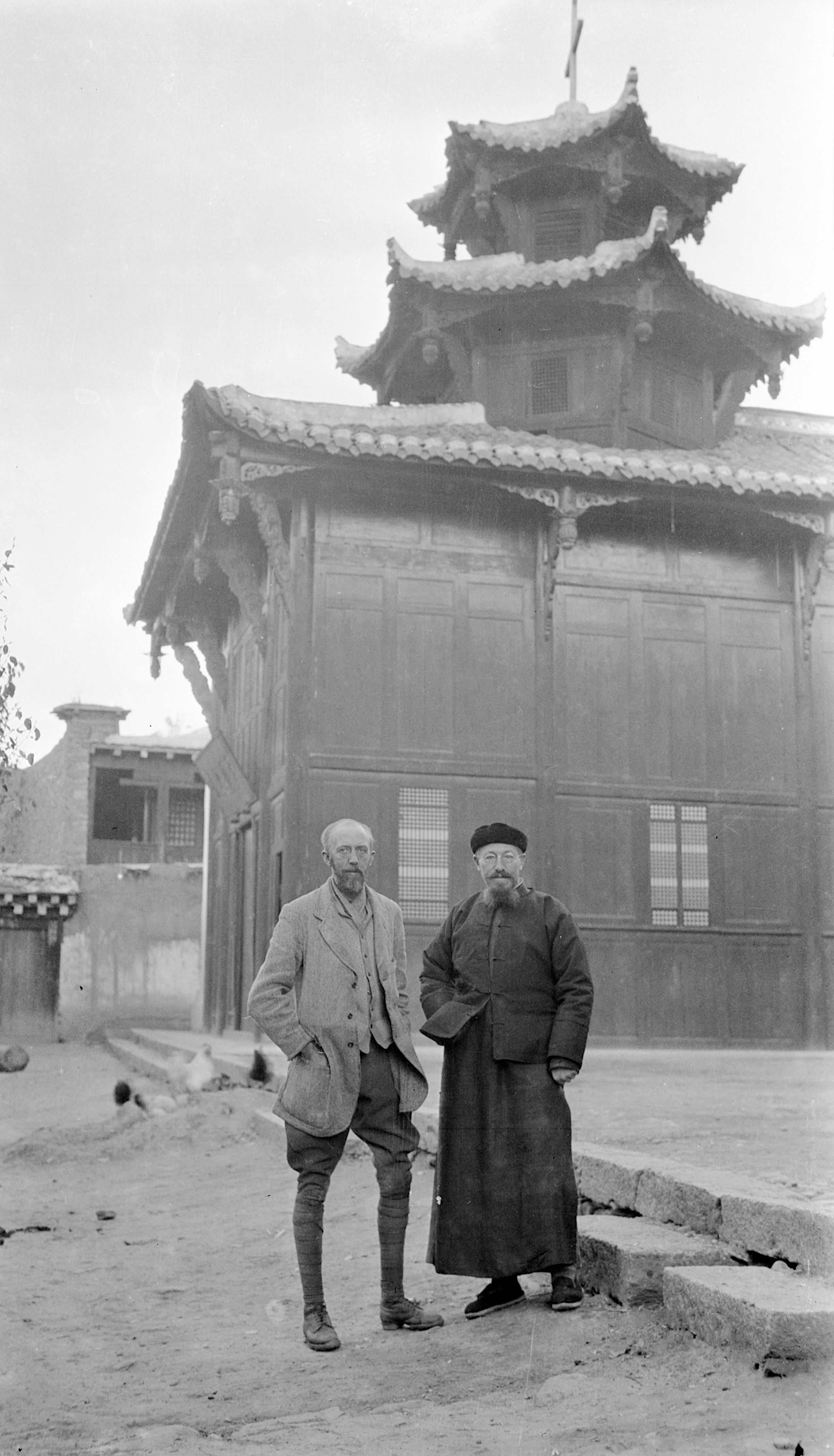

Père Rénard at the Catholic mission at Sharatong after the earthquake

Père Rénard at the Catholic mission at Sharatong after the earthquake

“Père Rénard is in charge and gave us a hearty welcome to the wooden building which they have erected since the earthquake. When the catastrophe happened, he was in Tachienliu. He was directed to proceed at once to Sharatong, which he did and after living in a tent for 3 months he got this wooden building up. He insists that it is not feasible to go on to Gonachung today even if the loads turned up soon, so I have decided to stay”.

“After a good look around, and then some lunch, (I arrived at 1.12), the details of the stone for Pereira's grave were agreed, subject to approval of his friends and family in England. I then went with Père Rénard to see some sick people in the village. One or two were the result of injuries sustained during the earthquake, but mostly the people are suffering from a sickness which had been prevalent there over the last 2 months. It seems to be the same as at Batang - a serious form or relapsing fever - some families have lost 2 or 3 members”.

“At 5.30 the loads and the boys arrived, just as it was getting dark. I was very glad to see them. I had some Chinese food with Père Rénard at 6.30 - then filled in the map of today’s route and went off to bed”.

Day 104 October 29th, 1923 Sharatong to Cheih Chu (Chiang Chen Chao) - 17⅔ miles

"We said goodbye to Père Rénard at 7.35 a.m. and hoped to reach To Chai by the evening. We stopped at Jara Chung for our hour's rest (11.45 to 12.45) and then pushed on again”.

“Some of the yak are such feeble beasts, if they we try to push through, one or two will inevitably collapse, which will be a problem for the beasts and their owners. So, as it was nearly 4 o'clock I decided to stay at this place Cheih Chur (Chiang Chen Chao in Chinese) (10,700 ft.) and leave the following day at daylight, in order to reach Da Wu in good time”.

HGT on the road looking NW up the Shi Chiu River between Kanze and Da Wu

HGT on the road looking NW up the Shi Chiu River between Kanze and Da Wu

“Père Doublat is stationed at Da Wu and as he was formerly at Yakalo, where Père Goré is, I am sure I will have a warm welcome. I am going to send a messenger on in advance tomorrow to ask him to send in a request for oola (yaks) for the next day, for we change oola (yaks) again at Da Wu (Tao Wu). Then we shall lose no time. At Da Wu we leave the Tachienla Road and strike North to Suching”.

Having finished the day's mapping and written his letter home, he had dinner and then went off to bed, as the plan was to leave the next day just after daylight.

Day 105 October 30th, 1923 Cheih Chu (Chiang Chen Chao) to Da Wu - 17½ miles

They left at 6.46 a.m. as HGT wanted to get to Da Wu early. The road followed the She Chiu all the way; with the river slowly increasing in size and force.

View NW up She-Chiu to Da Wu

View NW up She-Chiu to Da Wu

As they journeyed the result of the earthquake of March 24 the previous year was evident everywhere. There was hardly a house standing which was not newly built, and at each place where he made enquiry it was the same story - the house collapsed, 1, 2, or 3 were killed - or in some cases an entire family had been wiped out.

“We learnt that Gara chung was formerly a prosperous little village with 15 to 20 houses - this was the worst spot, and out of about 150 people only 50 escaped. Most of those who had rebuilt their houses had got the stone wall ground floor finished, but had not erected the second story. At Gara there was only a small rest house, and perhaps 2 others re-erected”.

“The right bank of the She Chiu was wooded in places with pine trees, these pine trees are the haunt of the Chagba (highway robbers) who attack the caravans, or even occasionally a village”.

“Our yak are faring very badly; they are very feeble and small - often we only travelled about two miles an hour”.

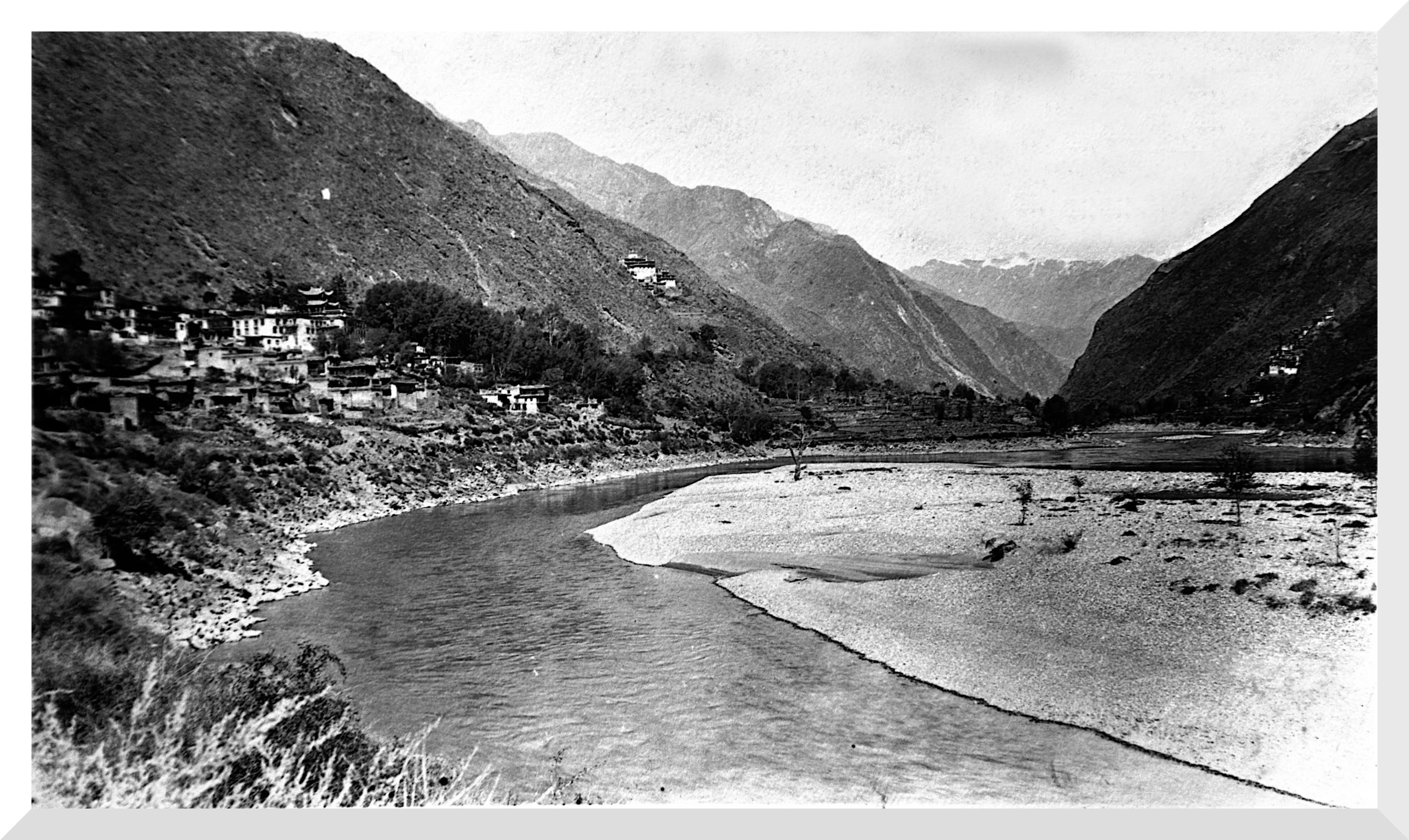

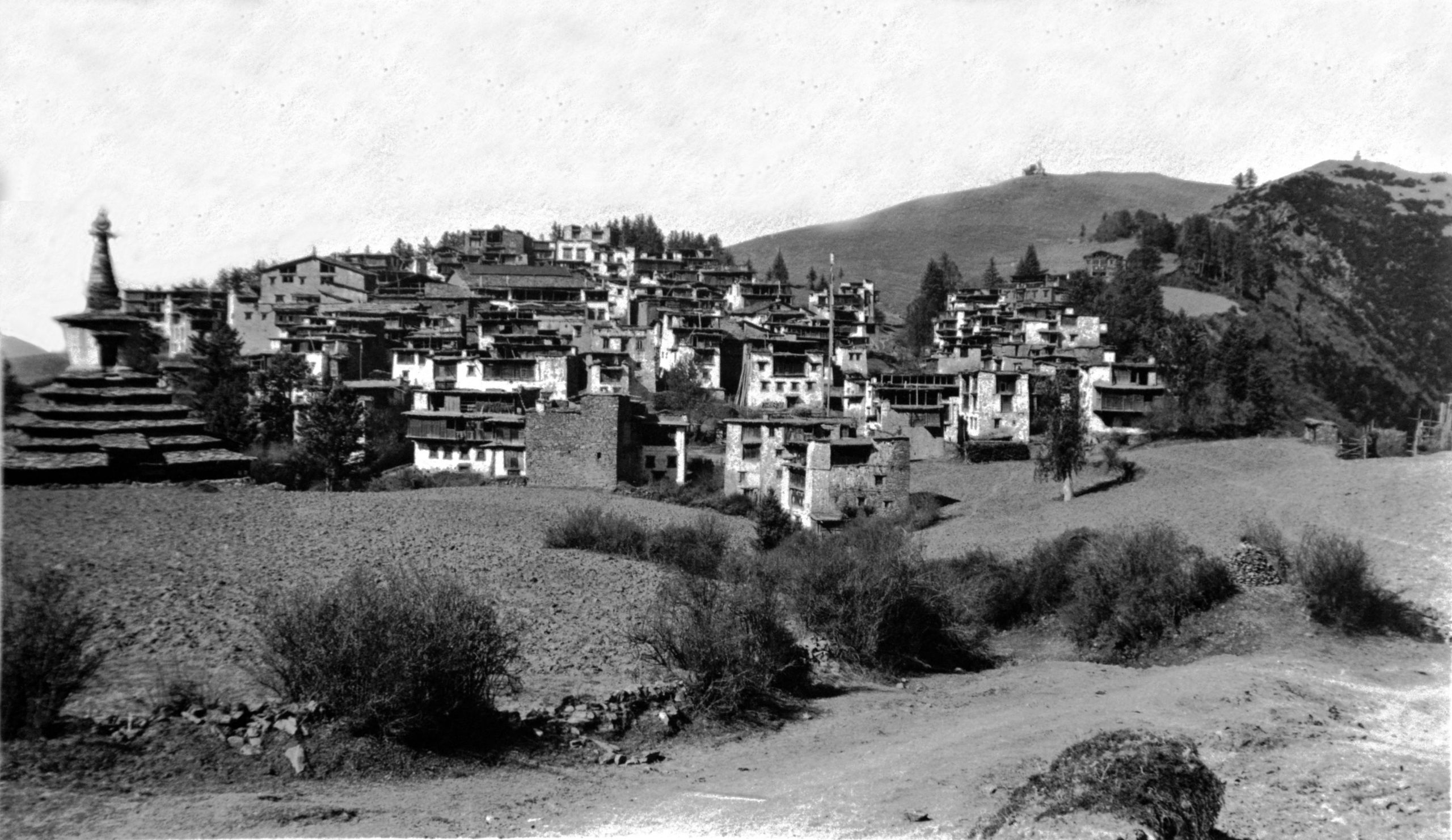

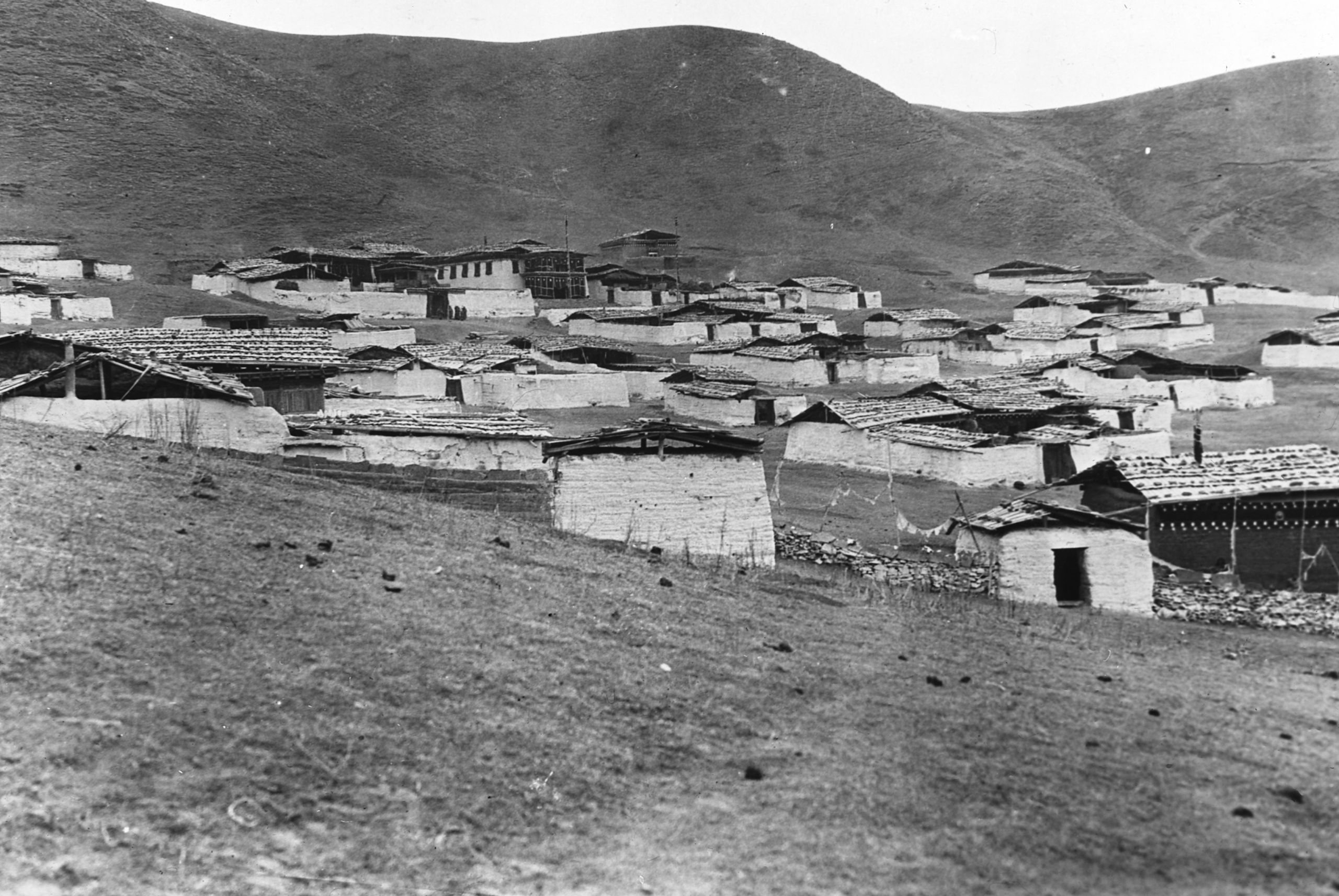

Approach to Da Wu (Tao Wu) on the Kanze to Tachienlu road

Approach to Da Wu (Tao Wu) on the Kanze to Tachienlu road

When they were about an hour from Da Wu, HGT took the boy and 1 soldier and went on in advance - after turning a bend Da Wu came into sight.

“There was a big lamasery (Ngistsa Gomba) with the white walls and the red lattice windows of the lamasery in the foreground with the snow-capped hills behind. It made a pretty picture with the sun shining brilliantly upon them. Da Wu (Tao Wu) (9,646 ft.) is not large, about the same size as Kanze, but many more Chinese. Pigs abound in the streets and Chinese shops; numerous butchers’ shops - pork butchers and other shops selling matches and small ware brought up from Tachienlu”.

HGT and Père Doublet at Da Wu

HGT and Père Doublet at Da Wu

The R.C. Mission at Da Wu was at the Eastern end of the village and consisted of a good compound with chapel and school and priests' quarters and a good garden. After their arrival Père Doublet sent for an old merchant who was engaged in the transport of goods, and enquired about their route. He advised them to take a route from Da Wu via Lung pu, Tan la, Kwan Cha Tsz, Sherh Lung lamasery, a kuchi to Lamba and on to Kung (10 days). This he said would avoid the Chagba on the main road, and also those on the Yako road. They decided to accept this advice and then consider the next step on their arrival at Rungya.

“Da Wu was very little affected by the earthquake, but Père Doublet tells me that it was very violent, and the whole ground seemed to rise and fall several feet. Some houses belonging to the Mission had collapsed, but the Mission building proper was unaffected. He himself (by the way he was wounded in 5 places in the war, and still had a German bullet in his leg!) started off at once for Sharatong - travelled right through without stopping for food and arrived to find the place in ruins, Père Abue dead and half the inhabitants of the place dead also, while practically all the rest had been injured by the collapse of their houses”.

“After lots of talk we fixed to leave tomorrow, Nov. 1st on the next stage of the journey. I will take with me, letters for the chief men at the two most important places in the next 4 days, requesting their assistance in the procuring of animals for transport. The mules will be 75 rupees for 2½ days’ journey, which I think is not so bad. I hope we will not lose so much time at our next stop. I anticipate that the next part of the journey will be the most difficult, and am hopeful that when we reach old Taochow the difficulties will be over”.

They were informed that the Goloks (Ngoloks) were at war with the Sata nomads, so it made it more certain that they would not have got through to the Golok camp.

“Later. Plans are changed again at the request of the local Prefect as the Prefects of Suching and Da Wu have not met. So, we agreed it would be better to go first to Rumichango - otherwise known as Tanba (Danba), and then up the river to Suching. It would mean an extra two or three days, but the road is said to be safer and better”.

HGT wrote in his letter home:

“It is a nuisance these delays, but it cannot be helped. All is now in order. Papers and soldiers are fixed up and we start tomorrow November 1st. Yrs H.G.T"

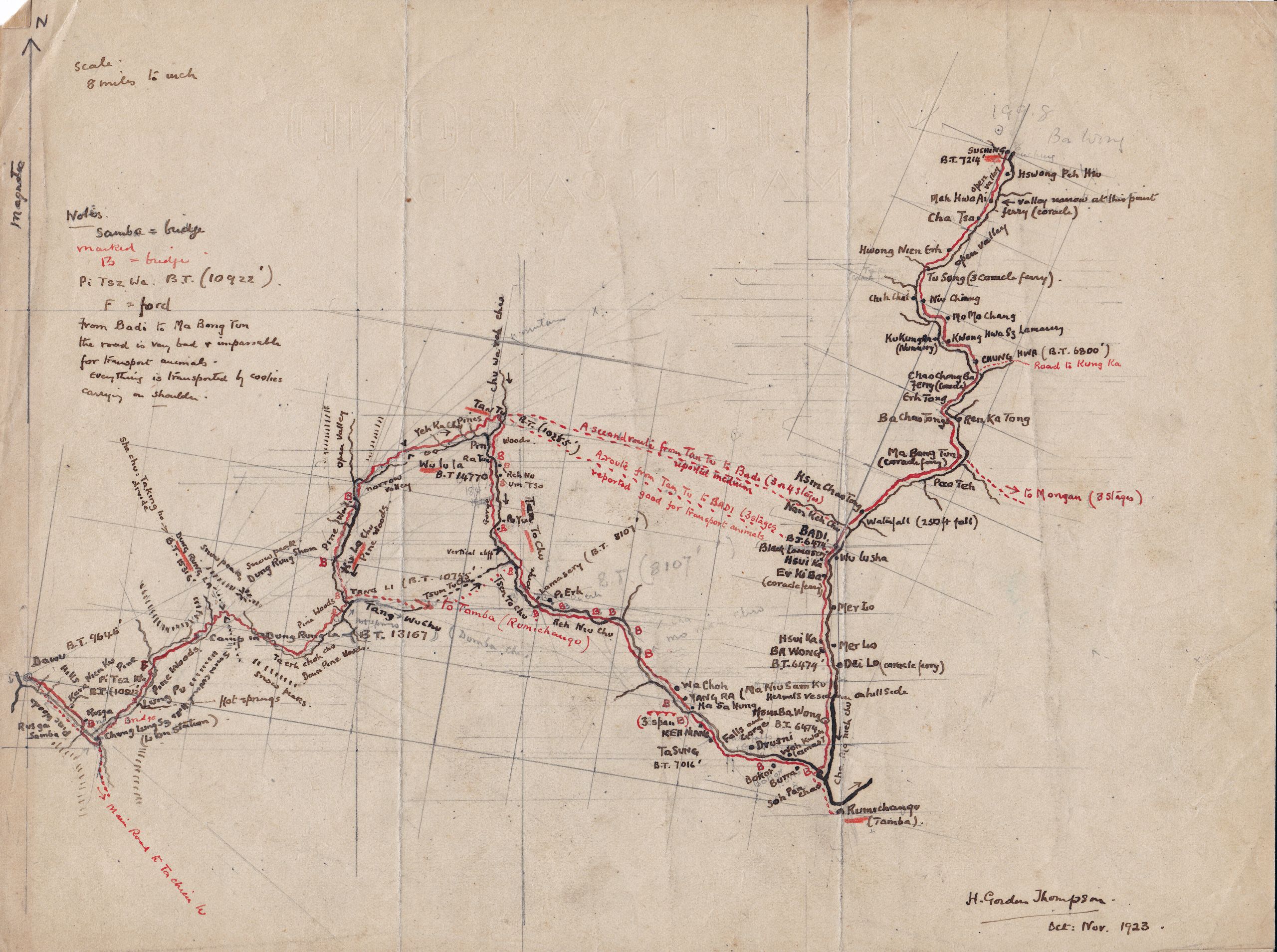

Hand drawn map from Da Wu to Suching

Hand drawn map from Da Wu to Suching

Day 106 November 1st , 1923 Da Wu to Dung Rung La camp - 20⅓ miles

“At last we are on the road again, after what has seemed like endless discussion. It is All Saints Day and Père Doublet is busy with special services, but not too busy to come out to see us start.”

They left Da Wu at 8.49 and after following the Tachien lu road for 8 miles by the side of a stream which joins the She Chiu, they branched off N.E. up a narrow valley - away at the top on the sky line they could see a snow peak called the Kung Rung Mountain. Just before entering the valley HGT noticed that they had not got the tent poles on the loads, so a soldier on his pony set off back the 8 miles to get them and then meet them at the camping place, - they aimed to camp at the foot of the Dung Rung Pass.

“Up the valley at a place called Lung Ru are some hot springs. The valley itself was narrow, and about half way up, the sides of the hills began to be covered with fir trees, with rhododendrons in great profusion. We followed up the stream in the valley and suddenly, although it was a big stream, I noticed the bed was dry. The stream which they were following disappeared and reappeared in the most extraordinary manner, part of its course being below ground. The muleteers who had planned which camping place to use, said it was all right, further up there would be plenty of water (so necessary for a camp for both man and beast). It turned out to be correct – we soon saw the stream again. It seemed that when there is not much water it sinks into the ground and reappears lower down”.

Setting up the Campsite atthe foot of Kung-rung-la mountain

Setting up the Campsite atthe foot of Kung-rung-la mountain

“We arrived at the camping ground (13,167 ft ) just as it was getting dark - It was bitterly cold and snow threatening. No sign of the soldier with the tent poles. At last, after I had got to work on the map in the open, with the camp table and a candle and nearly frozen stiff!! we heard a Tibetan “Halloo!!” down the valley and soon the soldier turned up”.

“Meanwhile the boys and muleteers had made a big bonfire and warmed things up a bit. The tent was rigged and soon all was snug”.

HGT wrote in his journal:

“I was glad he turned up - I am not a Tibetan yet. They all sleep out of doors rolled up in their sheep skin coats. We have had a small boy of 13 with us and I have christened him the "Little Mafoo". He is a jolly little chap in full Tibetan dress, but as the present mules only go two days we shall not have him after tomorrow.”

Day 107 November 2nd., 1923 Kung Rung La camp to Tang Li - 19½ miles

HGT noted in his journal that it was his mother’s birthday (Emma Thompson née Emma Stubley):

“The Little Mother's birthday. She little knows where her youngest son is!”

They broke camp in the morning with snow on the ground, glad that the tent had been all fixed for it would have been extremely cold to have spent the night out of doors, though the snow did come which made it a bit warmer. They were just at the foot of the pass and started off on foot. As they got higher they found deep snow, in places several feet deep, but the track was beaten out by a yak caravan ahead, so although it was also very misty, they did not miss their way, and in addition their 2 soldiers were just about 10 yards behind them. The boy and HGT went on ahead to get the boiling point and so the height of the pass.

“We overtook the yak caravan just at the top, and had great difficulty to get our water to boil as the wind was so strong. At last we found a sheltered spot behind a rock and got it going. The height is 15,316 ft.”

“I noticed that the boy seemed a little distressed, but he did not own up. I am sure it was the altitude, for when I had finished the observations I climbed up about 50 ft. to get a bearing with the compass, and when I reached my objective I could hardly stand. I was just gasping for breath. It was a most extraordinary sensation, and of course disappeared as soon as we descended”.

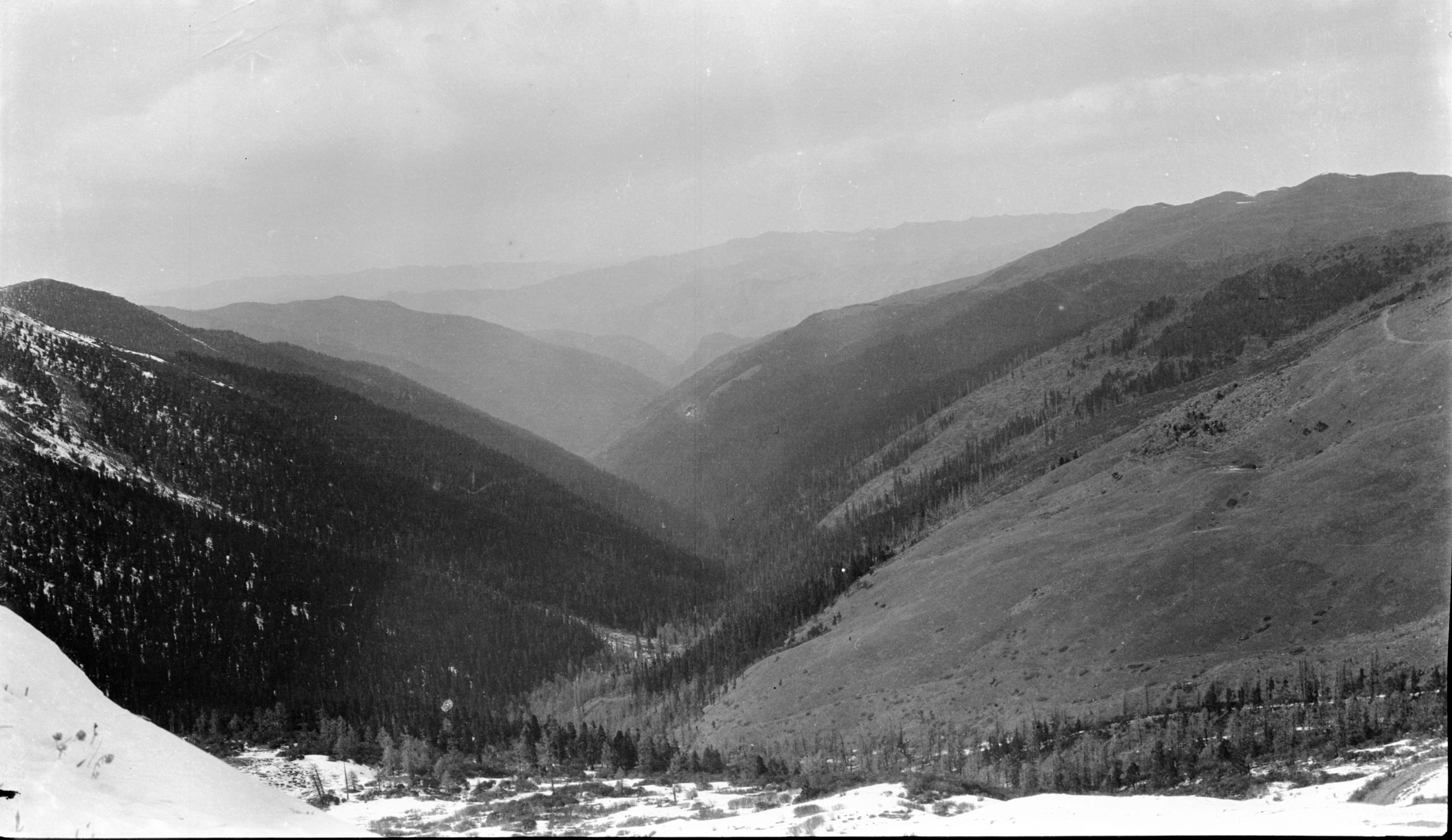

“The snow was deeper on the N.E. side of the pass, and in places my walking stick sank into the snow by the path side; up to the handle. We scrambled and slipped down about 1000 ft. and then the path improved and we were able to ride. The view from the top was grand; ragged rocky crags, all mottled where the snow had lodged in the crevices”.

View from top of Kung rung la pass between Erh-mo and Lamasery

View from top of Kung rung la pass between Erh-mo and Lamasery

“Away down below the fir trees are mantled in snow. Everything is beautiful”.

“Steadily we descended from the summit, which was the divide of the Rivers Sha Chiu (or Nya Chu) and the Ta Ling, and now we are following the river from its source up by the pass which will take us to Tanba (or Rumichango). On the way to Tang Li, we passed through great pine woods – where the boy tried to shoot a Ma Chi (a kind of wild turkey with white feathers) but was unsuccessful”.

The village, Tang Li, where they lodged for the night was only 10,755 ft. They had dropped 5,000 ft. and it was much warmer, moreover they were in a Tibetan farm house, which was miles better than a tent.

The boy 'Mafoo' at Tang Li or Ta Ling village

The boy 'Mafoo' at Tang Li or Ta Ling village

Day 108 November 3rd., 1923 Tang Li to Tan Tu - 24⅘ miles

“We have had a tremendous time of it”.

“We left Tang Li at 8.37 a.m. with the assurance that we could get through to Badi in 3 days, and so save 3 days by not going through Tamba. When we got up in the morning it was snowing lightly, but there was about 2" on the ground already. I have decided to follow the new track which has not been mapped before. Instead of following the Tang Li River down towards Tamba, we ascended the main tributary, reckoning that we would have to cross a pass. The first part lay through woods. It was a most wonderful scene. The snow on the great pine trees, and hanging from the branches the delicate flimsy creeper called the Bat's Whiskers, which gave everything a fairy like appearance”.

Snow in the woods just after leaving Tang Li village

Snow in the woods just after leaving Tang Li village

For 7 miles they passed through continuous woods which were on the lowest slopes of the hills on each side of the valley; no houses, only 2 nomad tents in the distance. Then their course altered more Northwards and they emerged into a wide valley about 2 miles across. A few horses and yak grazing near a nomad encampment. Two miles further on, and they entered a side valley and began a steep climb to the pass. One or two of the yak went down in the snow - now about 15 inches deep - but they got going again. Up and up, with the snow getting deeper, till at last they came to a clear space with rocky cliffs on three sides, and they had to climb over one of these crests. It was a knife edge pass. Every few steps they had to stop and rest both themselves and the animals. Slowly, step by step, it was accomplished. With a bitter wind and driving snow it was one of the most difficult they had had to tackle. A few feet from the top HGT with the boy and two Tibetans, turned off the track to get the boiling point.

HGT recorded in his journal:

“On opening the case my fingers were so cold, first the rubber disc and then the brass thermometer case slipped out and dropped into the snow - now about 2 feet deep. Fortunately the boy, after a hard search found them, but it took us half an hour to make the observations - 14,770 feet. Meanwhile, the caravan had gone on; the yak, now the pass was over, travelling splendidly”.

“The clouds and mist lifted a little, and I got a bearing with the compass. We slid down the first few hundred feet and I went full length into a deep drift, but was hauled out by the Tibetans. It was in no sense dangerous, but distinctly trying and difficult. Down from the pass and along the sides of the valley from the source of a stream, which slowly grew into a torrent. I was glad that I had put an emergency ration of 2 jam sandwiches into my pocket as we only stopped for about 10 minutes while the muleteers mixed some Tsamba with water from the stream and ate it”.

“It was still snowing slightly - but every 100 yards seemed an improvement. We passed two small cabins just below the pass, and after 4 miles of bare hillside, we again entered woods - down, down, down; the snow getting less deep; until about 1 mile from our destination it ceased. It was a descent of 4,500 ft. from the pass till we reached the valley”.

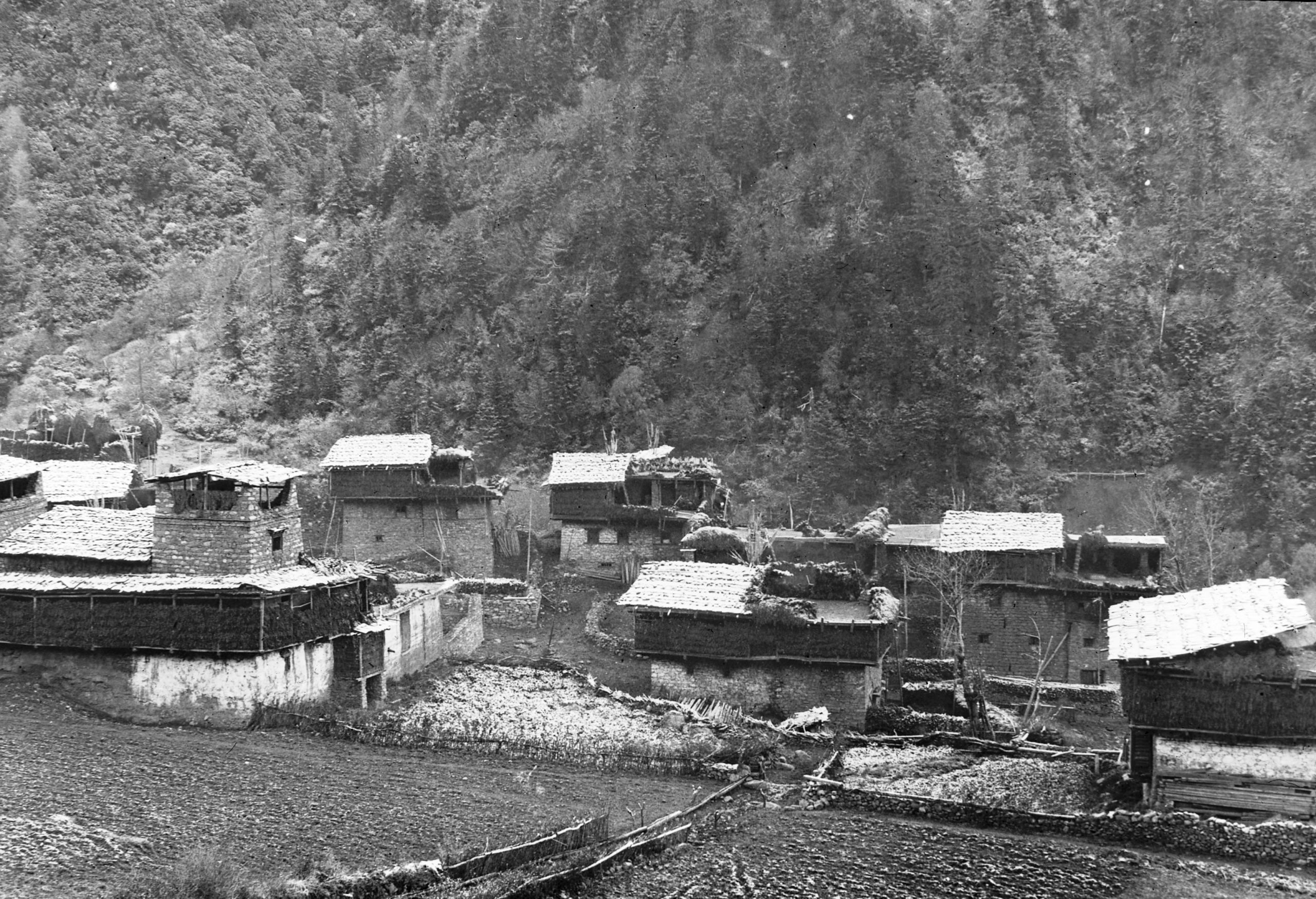

Village of Tan Tu

Village of Tan Tu

“Tan Tu (10,255 ft.) is a village of 60 families, and is presided over by a woman, Tu Sz, or headman. Her house is the largest in the village and she reigns supreme. Outside her room are hanging 2 batons with which she orders justice. They stayed in her house and on arrival there was a Lú (Lo pan) fire which we got going. I sat by it eating toast which I made myself, and drank tea - while the boys had their rice and then prepared dinner. I managed to get the old lady to allow me to take her photograph with her son and daughter and with the two lamas who are her private domestic chaplains”.

Headwoman at Tan Tu with her family and personal lamas

Headwoman at Tan Tu with her family and personal lamas

Headwoman at Tan Tu with her son and daughter

Headwoman at Tan Tu with her son and daughter

Day 109 November 4th., 1923 Tan Tu to Pi Erh - 17¼ miles

“We had such difficulty in getting the oola (yak), that I thought we would never get off, but at last we started at 11.43, leaving 4 loads to follow in the charge of one of the escorts. We pushed on with only 27 minutes rest for some food, and then on again steadily down the river from Tan tu, dropping in altitude about 2,000 ft.”

“At 5.30 it was beginning to get dark and we knew that there would be no moon. The muleteers kept saying it was not far, ‘just round a bend of the river’. At last at 6 o'clock it was quite dark - but still they said there was a little way to go to our destination at Pi Erh”.

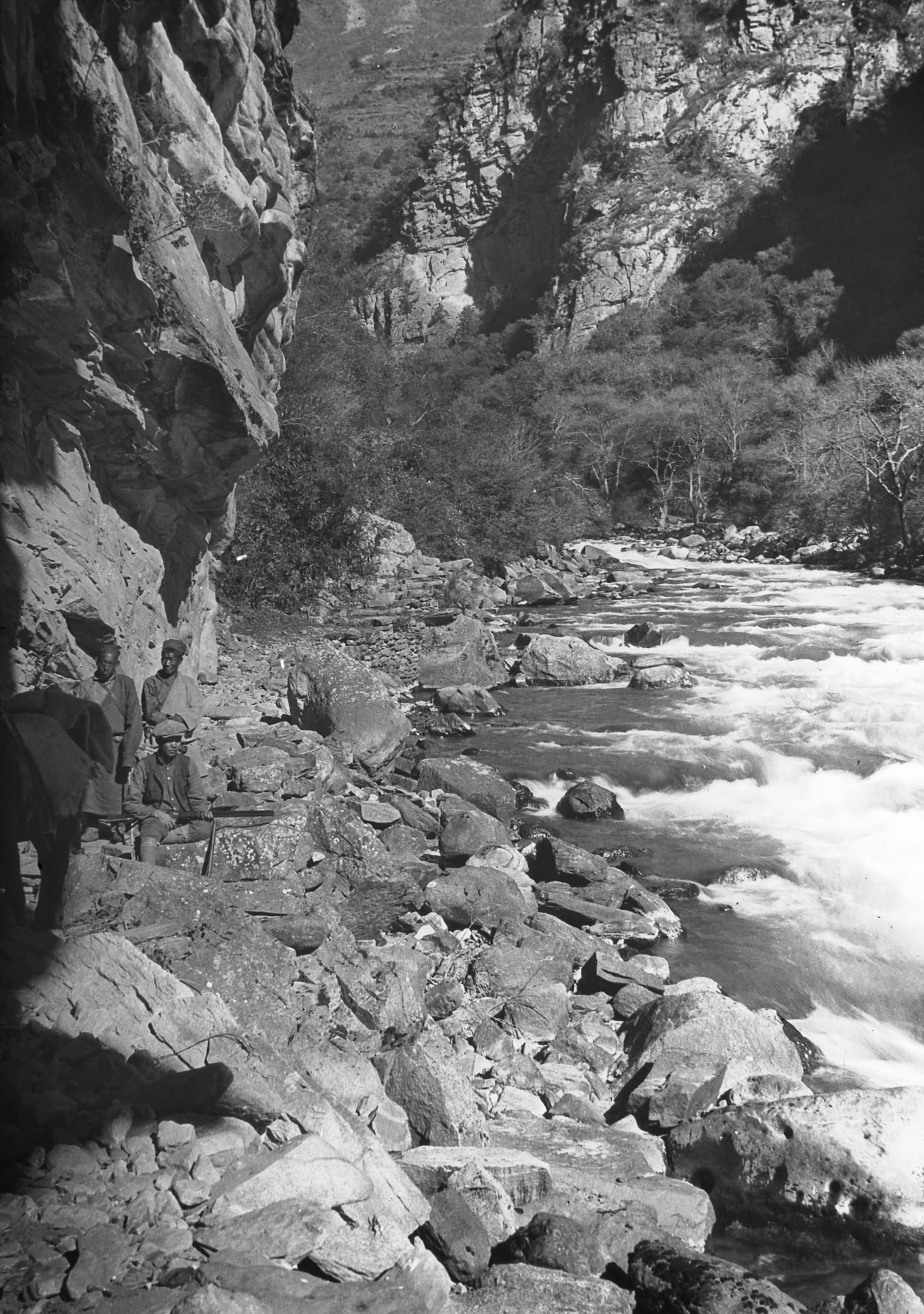

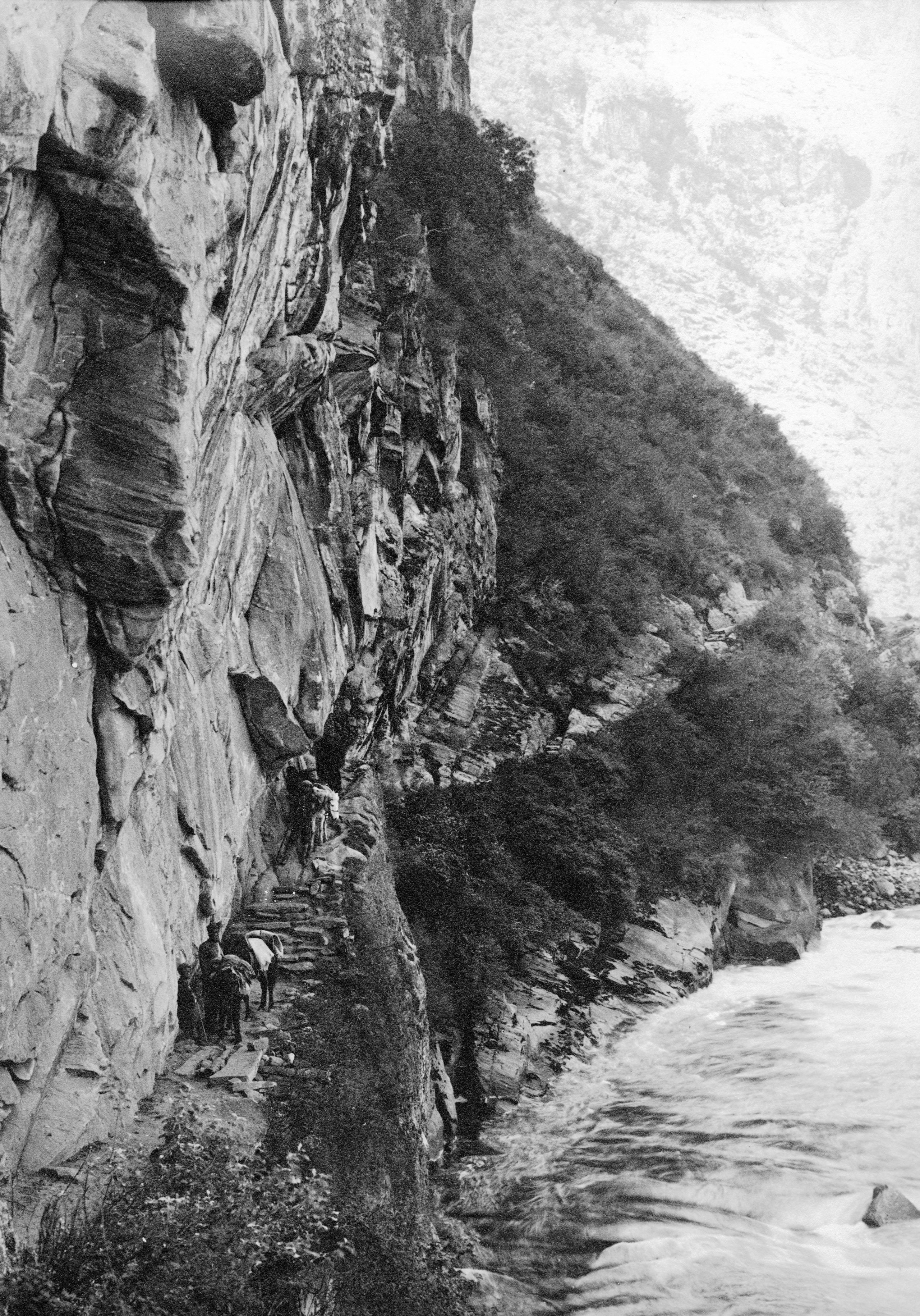

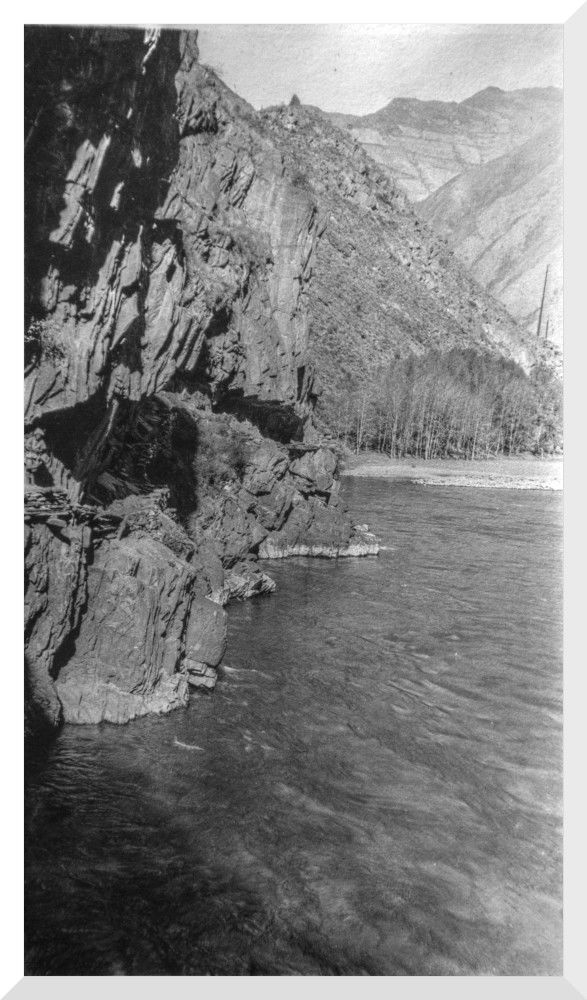

The river below Pi Erh

The river below Pi Erh

Gorge of river just below Pi-Erh

Gorge of river just below Pi-Erh

Rough road by the river below Pi erh

Rough road by the river below Pi erh

Another view of the rough road by the river below Pi erh

Another view of the rough road by the river below Pi erh

In his journal HGT described the last hour of the day as a "nightmare":

“I had a man leading the pony by a rope, and I just held on, the bushes with thorns often nearly swept one off their pony - and twice I lost my hat, and we had to light matches to search for it. The river, dropping so rapidly, was a roaring torrent and one could just see the white foam, sheer down below. We passed through a gorge with great towering cliffs and had to, as it were, feel our way. Then we came to a place where the muleteers said it was too dangerous to ride, so we all got off our ponies and felt our way along the narrow path".

"Fortunately, my pony was white so I could just see where he went and I followed, and the boy and the Tibetan boy tailed on behind. Then on to the ponies again, for the road was great boulders and the pony seemed to see better than I could.

"After a little way the Tibetan boy gave a yell, we got off our ponies to see what had happened and found the pony had got frightened and thrown him off. However, he seemed none the worse and on we went for it was impossible to stay there for the night. Then over a narrow path of sliding shingle - which gave way under one's feet and went rattling down into the river. At last - at last!. - the dim form of a building - a light, and we were at the lamasery in Pi Erh (8,107 ft.) where we took refuge for the night, and I slept soundly in a lama's cell".

Day 110 November 5th., 1923 Pi Erh to Ta Sung - 20½ miles

They got off in better time at 7.58 a.m. HGT had been awakened by the noise of numbers of women's voices in the lamasery courtyard. They were the carriers for the baggage - as animals would not be able to traverse that day's route - so this time the “oola” were nearly all women, who laughed and struggled over the boxes as they decided which they would carry. Altogether there were about 30 - including boys for the riding ponies - which of course they had to dismount when the road was narrow or dangerous.

women bearers who were replacing the oola (Yak)

women bearers who were replacing the oola (Yak)

“I went back a little to look at the road we had passed in the dark and wondered how we managed it - all credit to the ponies”.

“On arrival at Ta Sung (7,016 ft.), I could not find the small portmanteau which contained all the General's papers - maps - atlas and mapping instruments, also my papers and the map I have been continuing since the General died”.

It also transpired that the boy who would have known its whereabouts, had disappeared on the last stage of the previous day’s journey.

“I was very upset and sent for the head man who was responsible for the oola (yaks) and told him he must find it. He said “ Oh, it arrived here early and I thought it was to go on at once, so I sent it on and it is somewhere on the road ahead. -- It was an anxious night!”.

Day 111 November 6th., 1923 Ta Sung to Upper Ba Wong - 14 miles

“We left Ta Sung early and to my great relief the portmanteau was recovered intact, 9 miles further, when we caught up with the boy at Burra”.

The riverside road! by the Reh Niu Chu between Ta Sung and the main river

The riverside road! by the Reh Niu Chu between Ta Sung and the main river

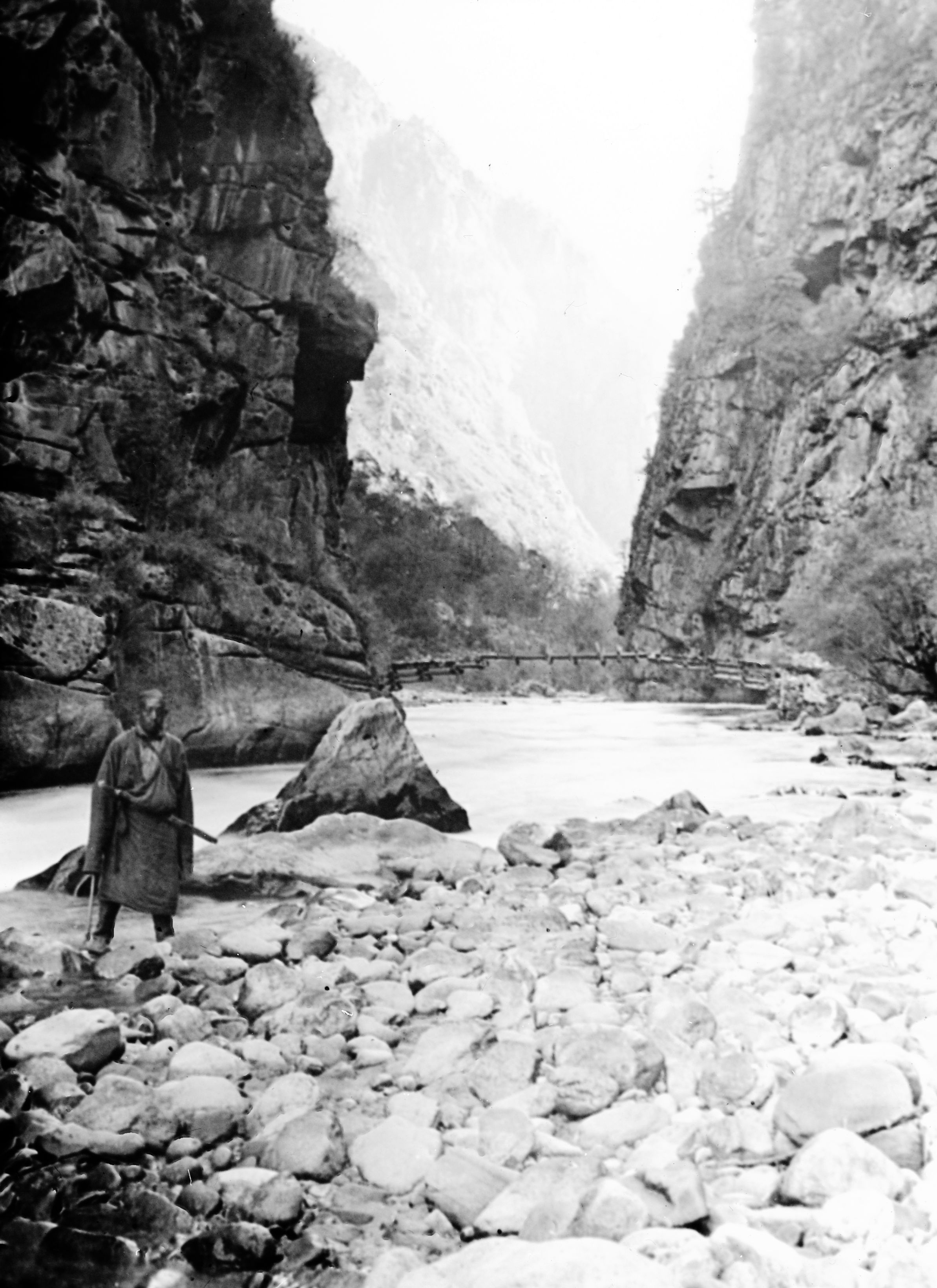

“From Burra we continued down the small river to where it joins the main river and then we left the Rumichango (Tanba) road, crossed the bridge - changed escort, and continued up the main river to Ba Wong”.

Lower down the river below Pi-erh with rough road and the bridge in the background

Lower down the river below Pi-erh with rough road and the bridge in the background

“At each small village down the valley I noticed that great towers - like the chimney of a factory back home in England - have been erected, and I am told it is the Tibetan way of protecting themselves from bandits. Round each tower are clustered several houses, though some towers stand alone. In one village I counted 12 of these towers. They give the place an extraordinary appearance. The houses were built of stone and each had a little tower with 4 pointed corners, which gave them the appearance of a country church in England”.

The river and terraces with the village of Ba-Wong (mid-distance)

The river and terraces with the village of Ba-Wong (mid-distance)

"We arrived at Ba Wong (6,474 ft.) at 4.50 and were then on the main road to Suching".

Day 112 November 7th., 1923 Ba Wong to Ba Di - 15 ½ miles

“The oola (yaks) system of transport is very trying – we changed carriers 3 times today and at the first change lost 1 hour and at the second, 2 hours. As a result, the loads did not arrive till after dark. However, the boy and I had gone on ahead and they arrived at Ba Di (6,474 ft.) at dusk".

The river valley on the approach to Badi

The river valley on the approach to Badi

“The big valley with its river is very beautiful, the white houses with their towers giving it a Swiss appearance - and make it quite picturesque. Many of the clusters of white houses are several hundred feet above the river. I finished marking up the day's journey on the map, and it seems to be working out fairly accurately”.

Day 113 November 8th., 1923 Ba Di to Ba Chao Tong -18¼ miles

“I had hoped to get through from Badi to Chung Hwan in one day (90 li). It was too much and we failed by 30 li. On these roads, we cannot make more than 60 li. The days are also now getting so short that we cannot travel after 5.30 p.m.”

“I felt more like a slave driver today than I have ever before in my life, as I urged the carriers on to try and get through - but we could not manage it and here we are in a farm house 30 li from our destination. It means that we shall do another 60 li tomorrow, pass through Chung Hwa and reach Suching the day after tomorrow, instead of tomorrow evening.”

“I shall be glad when we pass Suching and feel that then we shall be really getting on. We shall probably have a full day's rest there on Sunday November 11th.”

“The road was once again along the river bank, but it was execrable - up and down over narrow rocky ledges. No baggage animals could get through, except with very small loads, and they had to continually dismount whilst the ponies scrambled up the steps made of broken stones and bits of rock”.

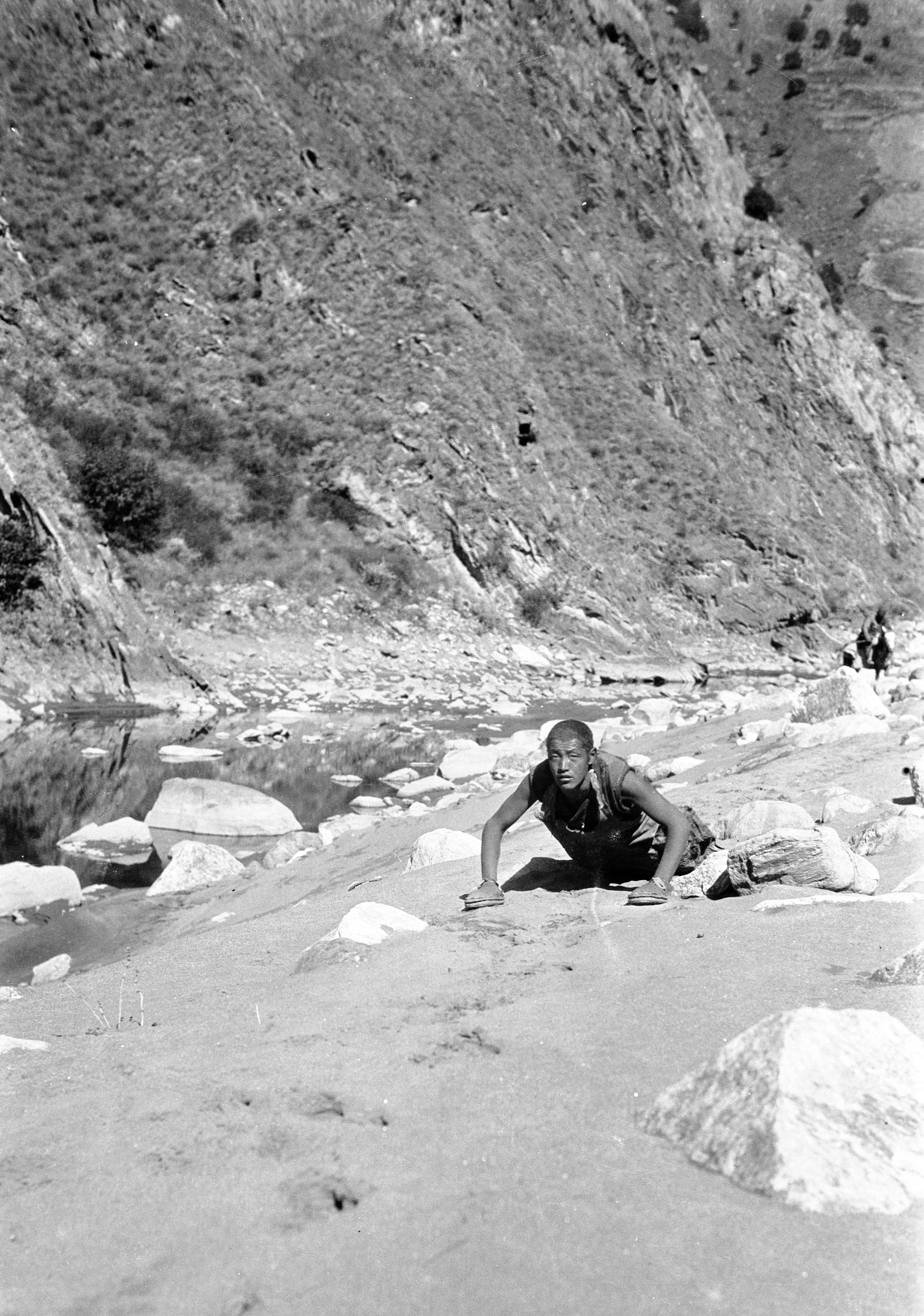

A Lama on a full prostration pilgrimage on his hands and knees

A Lama on a full prostration pilgrimage on his hands and knees

“On the road we passed a lama doing a pilgrimage - measuring his length on the ground and kowtowing each time. He had a kind of sandal on his hands to protect them. They said it would take him several days to complete his journey”.

Note: HGT is referring to the Tibetan Buddhist practice of full body prostration pilgrimage along a route around a holy site, or mountain or along the entire route to Lhasa.

The cliffs at Ba Chao Tong

The cliffs at Ba Chao Tong

The curious chimney-like towers were again evident when they reached Ba Chao Tong (6,800ft.)

HGT learnt that once they passed Suching, the system of Chinese officials would cease and the road would be looked after by the Tuh Sz (headmen) of each village.

Day 114 November 9th., 1923 Ba Chao Tong to Nieu Chiang - 13½ miles

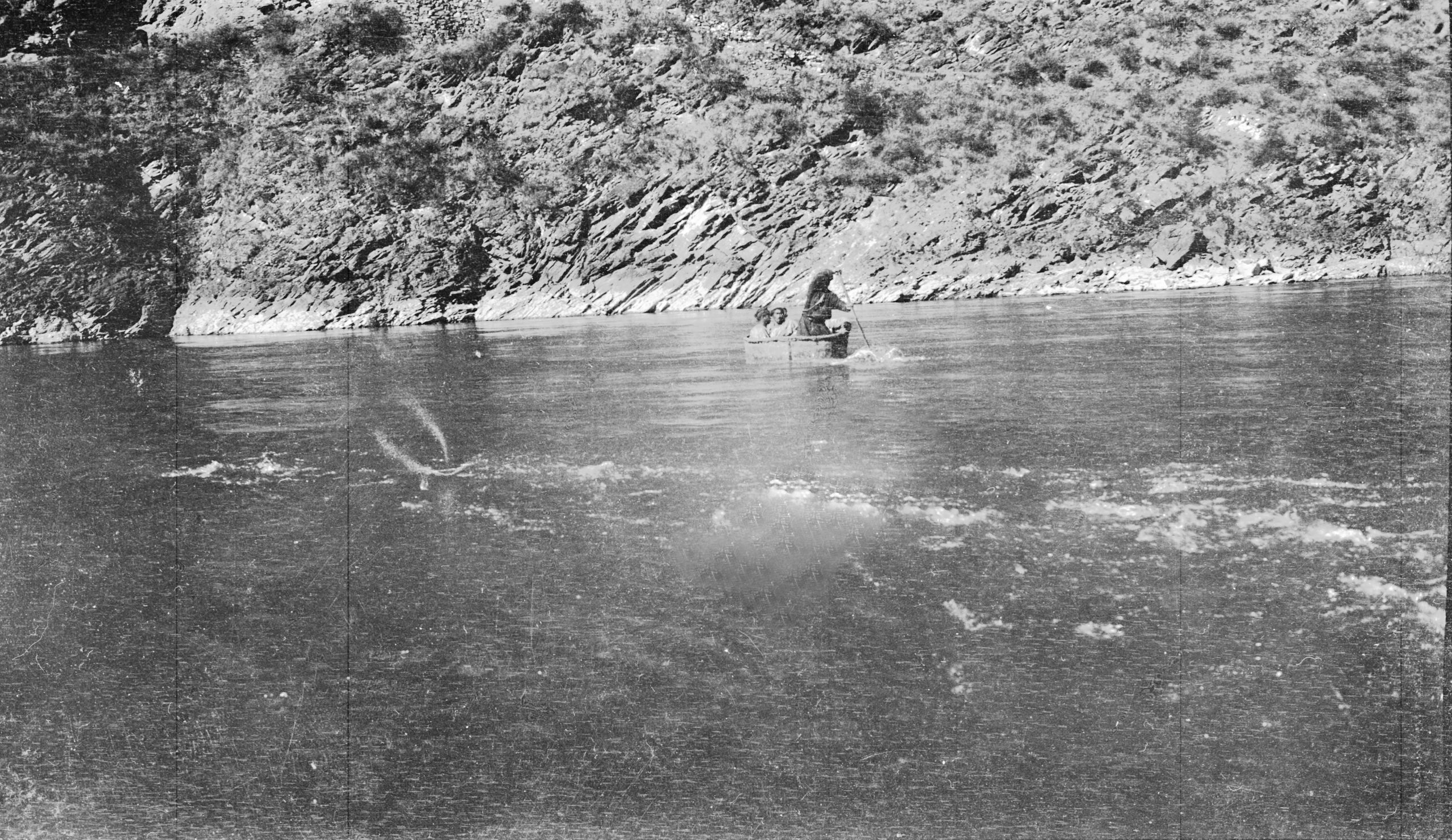

They started out in good time at 7.7 a.m. and keeping along the right-hand side of the river bank, they arrived at 9.04 at the Cheung Hwa ferry. It was simply a single coracle which only took 3 passengers and a couple of pieces of baggage at one crossing.

Coracle ferry at Cheung-hwa

Coracle ferry at Cheung-hwa

“So, as you may imagine, it took some time. We had 18 bearers with their loads, besides ourselves and the soldier escort etc. I crossed over with the second boat load and then the boy came over with the (Muslim) guide - Ah Hong - whom we had picked up in Kanze to help pilot us across the unknown country from Suching to Old Taochow”.

Leaving the rest of the party to follow, HGT, the boy and their guide (Ah Hong) went on ahead and arrived at Cheung Hwa at 10.10 a.m. Here they sought to change their bearers. There was an inevitable delay and they did not get started on the road till close on 3 o'clock. After that, they travelled a further 7 miles to Nieu Chiang (6,800 ft.) and as that had taken 23 li off the forthcoming journey to Suching, they hoped to manage it in one day and then have a full day's rest on Sunday.

Day 115 November 10th., 1923 Nieu Chiang to Suching - 15½ miles

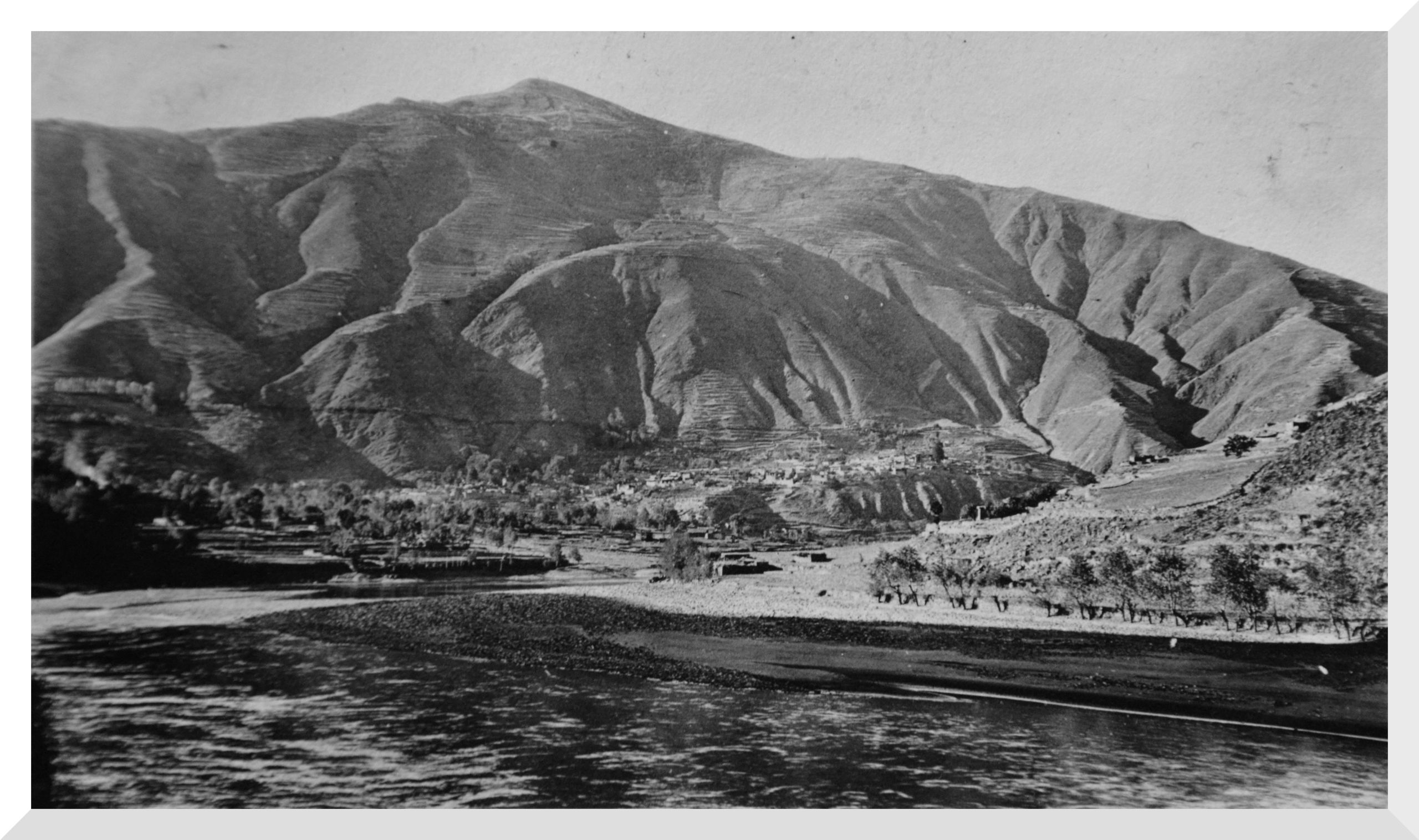

After 15½ miles they made it to Suching (7,214 ft.) safe and sound. They had a very uneventful day, following the Ta Ho (big river).

“We (again) had to cross by a coracle ferry but there were 3 coracles and we got over it in half an hour, which was not bad for nearly 30 persons and the baggage. The old man at the coracle ferry told me that he had been on the job for 40 years, and hoped to comfort me by saying that the previous day a coracle either gave way, or was upset, and 3 out of 4 people in it had drowned!”

“Suching is a very pretty town. We approached it from the South and the trees - scattered about are showing their autumn tints - brilliant yellows and red – which makes it very picturesque. There is a big bend in the river and we are told that there is a road which comes direct from Taochow and which takes about 5 days”.

The approach to Suching from the South

The approach to Suching from the South

“I hope tomorrow (Sunday) will be quiet. We will leave again on Monday morning pushing on North to Danba and Chaoser. The road ahead sounds quiet and peaceable. We have fixed up ponies for Monday though could only arrange them for 3 days and then there will be a change again”.

“Overall I am pleased to be getting back onto ponies, mules, or yak for transport as the bearers are often difficult. Some are opium smokers - wanting to stop every few minutes to rest, and at the first, to go and have a smoke".

There was a P.O. in the town so HGT was able to post one or two letters.

“Ever since Ba Chao Tong, the river valley has been getting more and more Chinese in population and at Cheung Hwa (yesterday) we saw the first proper Chinese shops since Kanze and Li Kiang, and it felt like old times being able to talk to the people in their own language after having to try and converse in Tibetan by interpretation”. On the other hand, the inns and houses and shops are now often dirty – This seems very strange after the clean floors of the Tibetan house guest rooms”.

Day 116 Sunday November 11th, 1923 Suching

“We have had a quiet day resting and preparing for the next stage of our Journey. All is fixed up for the pack ponies for the next three stages and I aim to leave at daybreak. The road between Suching and Sotsong Gomba – which as far as I am aware, is hitherto unmapped – is reported to be safe and free from bandits, so although we will still have to camp occasionally, I am looking forward to a peaceable route”.

“It is just 3 weeks to the day since we laid GP to rest, and already it seems such a long time has passed. I have not been to see the official in Suching as I do not wish him to begin to make difficulties, but I sent him word that we are leaving tomorrow and I believe he will be sending someone to escort us out of his district”.

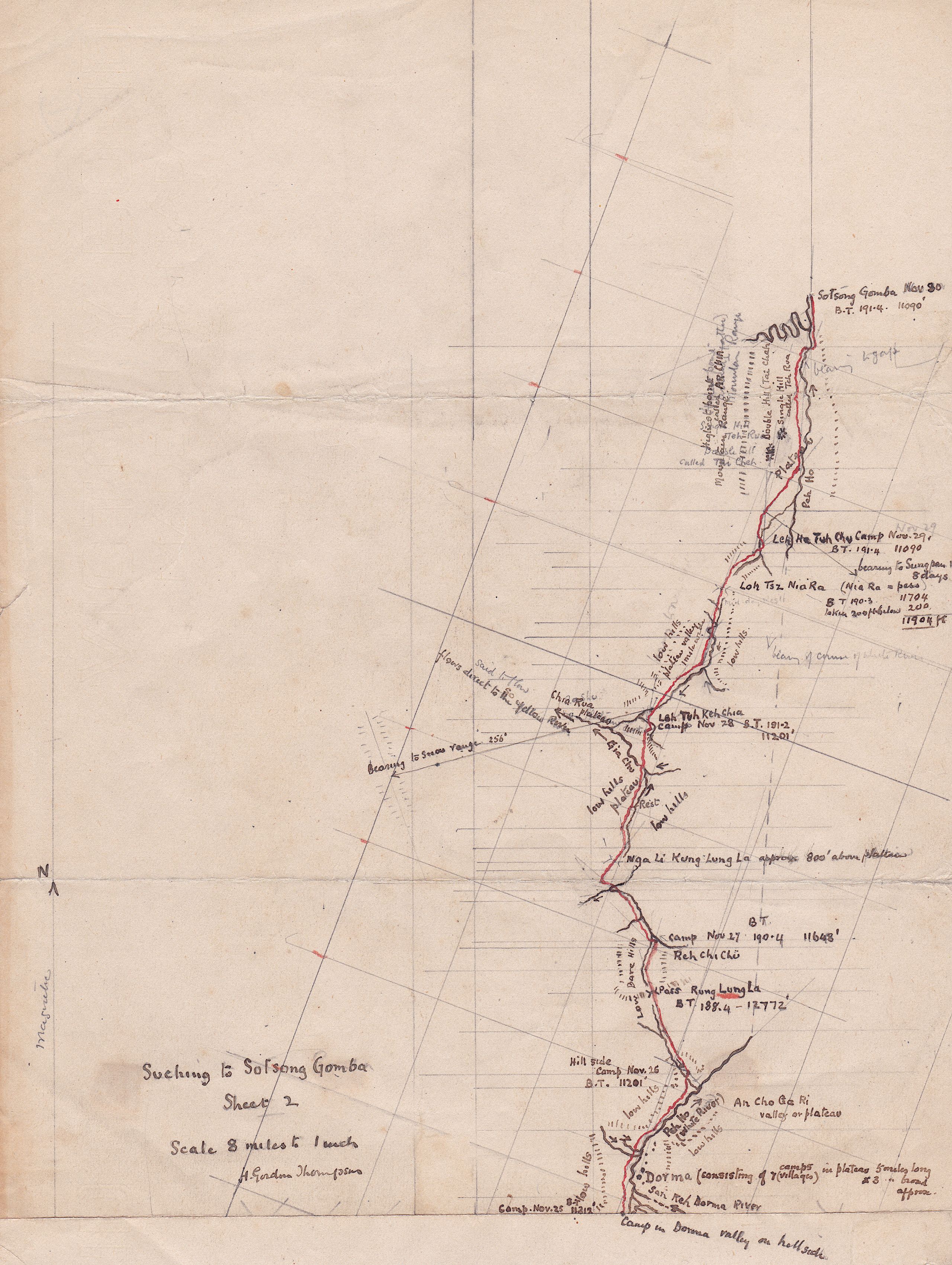

First part of the route from Suching to Sotsang Gomba - to the camp in the Tor Ma valley

First part of the route from Suching to Sotsang Gomba - to the camp in the Tor Ma valley

Day 117 November 12th., 1923 Suching to Teh Sheh Ti - 9 miles

They had hoped to start at daylight but eventually left Suching, at 12.30 noon. They said goodbye to Chinese officials for the time being and from there on would have to deal with the Tu Sz or headmen of the villages – who were generally Tibetan.

“We had a lot of trouble with the muleteers today and it was only at the end of the day that I found out the cause. In Suching we had arranged to give $3 dollars on arrival for these 3 stages which was considered a very fair price, but the official had made them go for $2. - and somebody pocketed $15, - out of $45, - which I had paid over before we left.

“I arranged to send a card back and ask the official to see that these people got what had been promised and what I had paid to the officials’ representative”.

“A couple of miles from our destination a well-dressed Chinese farmer came running after us and begged me to see his son who had got something wrong with his legs.”

In his journal HGT recorded how he felt.

"Oh, that I had the power of the Master to say, “Go thy way thy son is healed", but I have not, so I said "Bring him along to Teh Sheh Ti and we will see what we can do”.

“Less than an hour later the man turned up with a boy of eleven - a wee little fellow. He could not straighten his legs at the knees. I think that after rubbing with some liniment he should get alright. The father brought a basket of pears and walnuts and went away with 2 tracts, full instructions and medicine, and he promised to carry out the treatment”.

They reached Teh Sheh Ti (7016 ft.) having only managed about 30 li in the day instead of 90 (approx. 9 miles as one Li was about ⅓ mile). They determined to leave at daylight the following day to try to make up time over the following two days otherwise they would have lost a day by having been late in starting out.

“Everybody continues to report that the road is safe though it has only been useable for the last 18 months”.

Day 118 November 13th, 1923 Teh Sheh Ti to Erh Mo - 13 miles

“We left Teh Sheh Ti at 7.5 a.m. with the hope of reaching Nieu Chang and so getting to Cherh Tsz tomorrow, but the ponies are so slow that we could not manage it. Oola (Yak) are obtainable along this route, but the road is so narrow and difficult along the side of the river that pack-animals can not be used, and our riding-animals had difficulty along some of the track. We planned to get to the Danba valley for our mid-day halt. The Danba is a Tibetan inhabited valley with scattered farm houses, and one great big residence with 2 towers which is the house of the Tuh Sz headman".

The first part of the day was spent steadily climbing up a narrow valley - the road zigzagging in places just following the mountain stream which ran down the centre of the valley itself. After 4 hours of this they crossed a ridge and got a clear view of the country looking down the valley back towards Suching.

Skirting round the side of this mountain slope they then crossed another ridge at 1 o'clock and just below them was the Danba valley, with the Tu sz's residence and other farm houses.

Looking down from the snow line to the wooded Danba valley

Looking down from the snow line to the wooded Danba valley

“We called a halt for lunch for we had had breakfast soon after 6 am and we were ravenous. Food was prepared and served up at 2.15 – and at 3.10 we were on the road again. We cut across the top of the Danba valley descending somewhat into it and then following up the Danba stream. At 5.08 we reached the little village of Erh Mo on the hillside (10,588 ft).

“It is getting dark and I have had a racking headache all day so I said ‘Whatever place this is, we will stay the night’. The Tibetan boy at once went to the cluster of houses - only to find everything shut up and doors and windows closed. Not a sign of life except the dogs. However, he persisted as we knew there must be someone about as there was some smoke coming from one of the houses, and at last we gained admission. The people were simply frightened - but we soon reassured them”.

HGT wrote in his journal:

“Right glad I was to finish off the day's mapping and turn in to bed after having some supper”.

Day 119 November 14th, 1923 Erh Mo to Tsa Koh Gomba - 15 miles

“After a good night's rest, the headache was gone. We had breakfast and were on the road again at 8.08 a.m. We decided to start early as we knew we could not make Cherh Tsz today, so we took things easily. I took a course towards the north-east, and there followed a long continuous 4-hour climb till we once again reached the snow line at 14,000 feet. We crossed the Tan Chao Wu (pass) at 11.50 a.m. (14,130 ft.) – with snow about 1 foot deep. From there we descended into a small valley, crossed over another lower ridge and entered the valley which was then downhill to Cherh Tsz".

"At 1.49 we reached a little house inhabited by 2 Tibetan women who kept one or two pigs, and yak on the hillside. We had lunch, then at 3.11 travelled on down to the Lamasery Tsa Koh Gomba (10,199 ft.)".

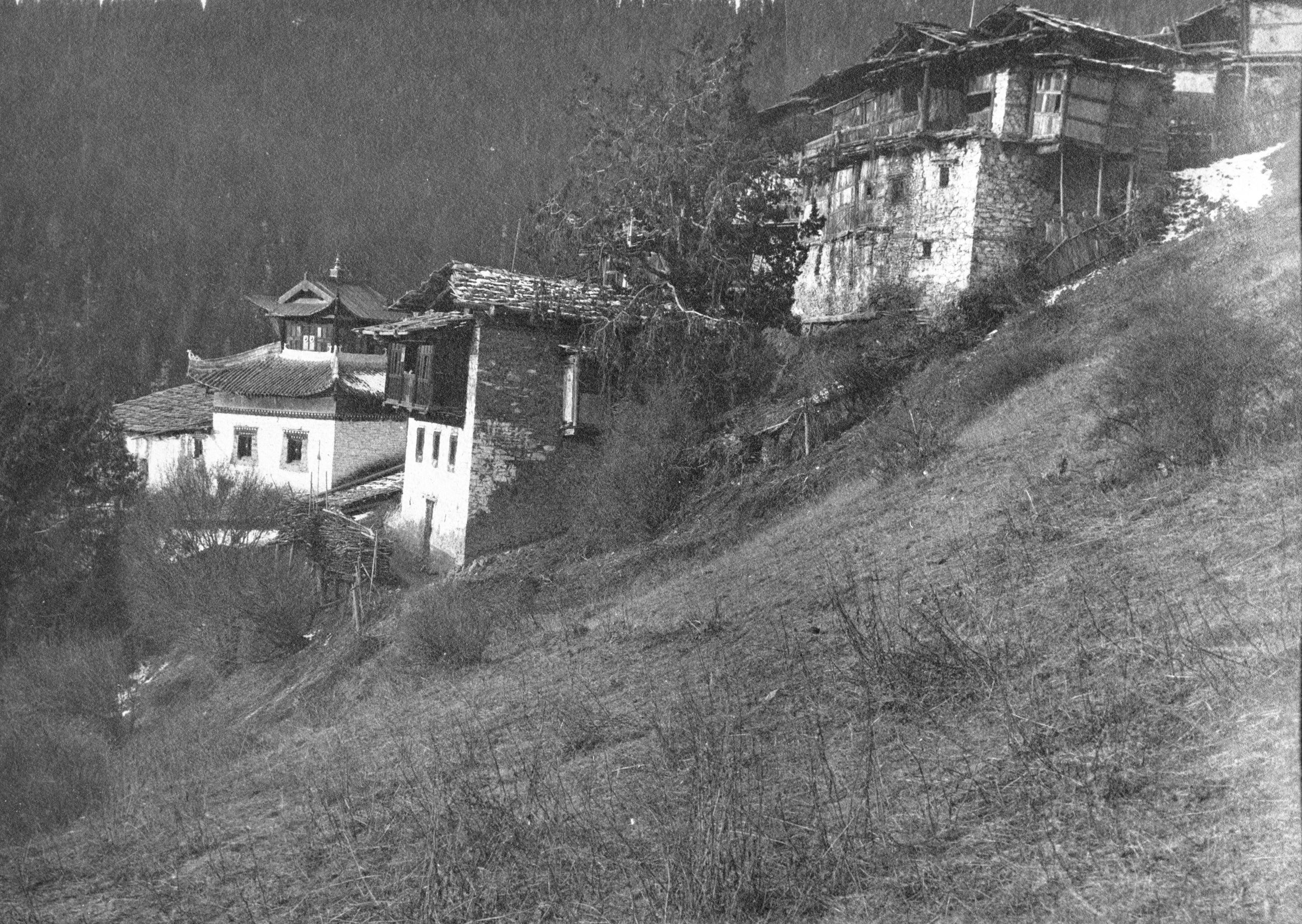

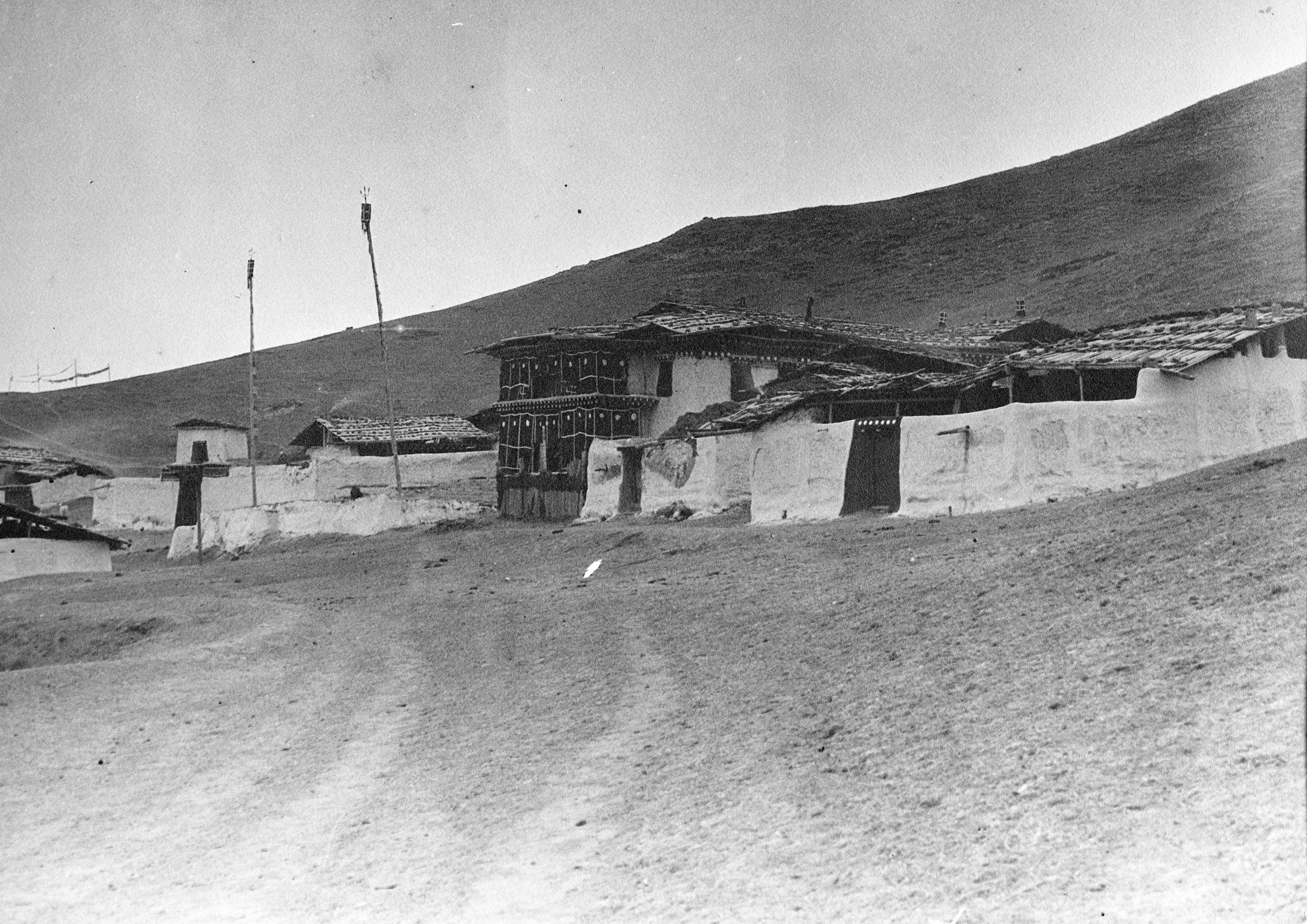

The Lamasery Tsa Koh Gomba

The Lamasery Tsa Koh Gomba

Before leaving Erh Mo a messenger came from the Danba Tuh Sz and the Cherh Tsz Tuh Sz who was staying with him, with a card and a little present; saying that the office of the Cherh Tsz Tuh Sz would give all assistance on their arrival.

“The old man who brought this message on horseback, spoke Chinese and told me that last year an Englishman named Sz or Sheh (Shaw?) was reported to be coming through from Chengdu - but he never came. On arrival at the lamasery however, one of the lamas told me that a foreigner had stayed at the lamasery overnight the previous year”.

“When we first arrived at the lamasery, we initially had great difficulty to get admission, but at last I showed them Tuh Sz's card, and at once they became more active. The main part of the building was closed, but we put up in one of the lama houses. There are about 108 lamas connected with this place - but nearly all were away”.

Day 120 November 15th., 1923 Tsa Koh Gomba to Cherh Tsz - 9 miles

“Just a short stage of 9 miles today and the altitude has dropped quite a lot - It was a steady downhill all the way, and we are now on the banks of the Matang River - which is really the upper part of the river that was called the Ta-King Ho at Suching. We reached Cherh Tsz (8,674 ft.) at 11 a.m. and took a rest day, as we prepared for our next push of 8 days to Sotsong Gomba”.

The house of the Tu Sz at Cherh Tsz was a great big residence, more like a small fort with 2 towers; typical of several which they had seen en route.

The Tuh Sz's (headman) house at Cherh Tsz - with the traditional tower

The Tuh Sz's (headman) house at Cherh Tsz - with the traditional tower

Day 121 November 16th, 1923 Still at Cherh Tsz

“Last night, the representative of the Tuh Sz had visited me hoping to persuade me to go via Somo and Matang. When asked the reason, he said that there was a feud between two of the lamaseries we are due to pass, one 2 days north, and the other 4 days north, and he thought we would not get through”.

“I asked if there was any fighting, but was told, “No, not exactly fighting". "Was the road not safe?" "Oh, yes, the road was quite safe". I said “Well, I do not wish to go via Somo and Matang, but if you tell me that this road via the lamaseries is impossible, of course I will go via Soma and Matang, but when I get through I will make enquiries at the other side, and if there is no cause for altering my route I shall be annoyed", and I looked at Tuh Sz's representative as if my annoyance was a most awful thing to be reckoned with. Then it all came out that the Tuh Sz house is not friendly with the lamas and did not wish me to go that route because all he need do was to write a letter asking them to see us through if there was any difficulty in obtaining animals, and he would rather not do that. I pointed out that this was a simple matter, and after discussion they agreed to write the despatch, and also send a representative along with us. Then they said "We cannot have the animals ready by tomorrow", so I gave way and said we would wait another day”.

Day 122 November 17th., 1923 Still at Cherh Tsz

“A day to visit and prepare. By our planned route we aim to save a day on the road and we are due to go through country peopled by nomad tribes, either Goloks (Ngoloks) or Ngaba (aka Ngawa), it remains to be seen which. The other route would take us nearer to Singpau and be much more Chinese in character”.

Note: Ngaba (or Ngawa), is now the name given to a city of around 15,000 (mainly Tibetans) and the administrative centre of Ngawa county in the northwest of Sichuan. It is said by some to have been the capital of the ancient semi-independent Mei Kingdom, claimed by both Tibet and China but in fact ruled autonomously by a local dynasty.

“As I am writing this journal, the great 15 ft. long trumpets of the small lamasery are blaring out their droll notes, and the lamas are busy intoning their prayers. This is done night and morning, at sunset and daybreak, and is accompanied by the shrill notes of shorter trumpets played in a tremulous way in a kind of minor key – which is very weird.

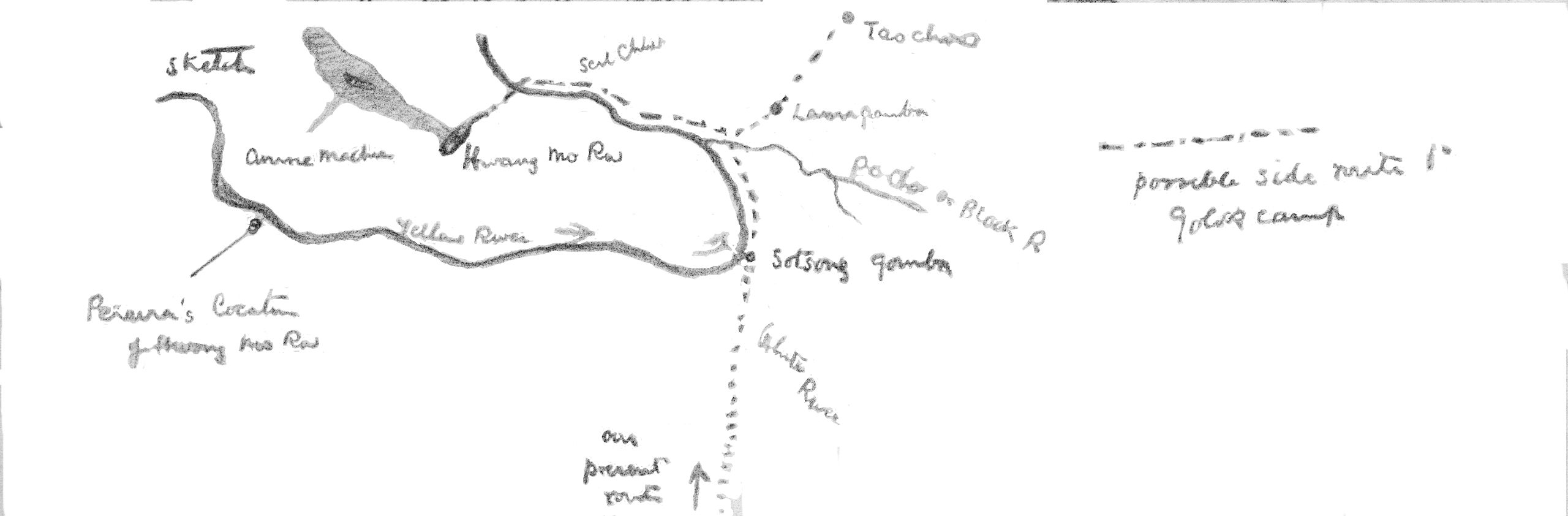

“I spent the day trying to determine the position of the Golok camp capitol, where the Queen of the Goloks lives. These camps are moved about to provide fresh pasture for the animals, so it can only be fixed approximately, and as no Emperor has ever visited Hwang nw-nw, (the name of the camp), it is not marked on any map. Pereira had thought it was on the right bank of the Yellow River on the southern part of the great bend. Both the Tibetan boy and Ah Hong, our Muslim guide - whom I engaged at Kanze - had visited the camp, the one having come down to it over Tangai in the North and the other having approached it from Taochow in the East. I got the two of them, separately and together, to help work out the location of the Golok camp. They seems to be no doubt that it is situated in the bend of the Yellow River to the East of the great (Tibetan holy) mountain Amne Muchin - something like this as shown in this sketch”.

HGT's Sketch map of planned route to the Golok camp

HGT's Sketch map of planned route to the Golok camp

“I am determined to find out if it is possible to get to the Great Camp once we reach Sotsong Gomba. It will probably mean a fortnight’s detour, allowing for 2 days at the Camp and I hope we may find a nearer route back to Tao chow tang. It all depends on 2 things;

- Is the country peaceable?

- Can we get transport (either mules or yak at Sotsong Gomba)?”

HGT told the boy to prepare potatoes and flour and sugar for one month. With these 3 commodities well in hand, he thought they could manage other things. He wrote in his journal:

“Jam, we have a good supply; baking powder sufficient; butter, just about enough to last out to Lanchow, and one or two tins of stores which I have been saving for emergency”.

“Generally the boy shoots pigeon or partridge or wild duck enough to keep one going in meat - If we can do the Golok side trip I want to do it, as it is an opportunity I shall never have again, and it looks as if the way is all prepared, for Pereira has asked General Ma Chi at Tangou to send word that we were probably coming and to bespeak for us all necessary assistance. As the Goloks are now under General Ma's wing, this is important”.

Note: General Ma Chi was a Muslim commander who had fought in the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901). When the Emperor abdicated Ma Qi declared support for the Republic of China and became the military Governor of Qinghai. He ruthlessly supressed uprisings by Tibetan forces with his Muslim troops on a number of occasions.

“From the Golok camp it is only 10 days to Tao Chow tung, and 17 or 18 days to Lanchow, and then at one or both places ........ letters!! .......and news!! from Yunnanfu ......... then a day or two’s rest, and D.V. (Deo Volente) on to Peking and home. It sounds quite near already, and as I write these lines in this half Tibetan-half Chinese, village my thoughts fly across the intervening country, and I am with you all”.

Day 123 November 18th, 1923 Cherh Tsz to Ta Lung Chao - 12½ miles

“We left Cherh Tsz in the morning at 9.47 - The muleteers have a new way of fixing their packs. They are made up into 2 half loads, joined by a leather thong, and then lifted bodily and slung on each side of the pack saddle. Previously the Tibetans they had employed had fastened each half, separately to the saddle. This method is much easier to load and unload at the mid-day halt”.

View North in Washi country from Kun Chien La. The Hochu-Yalung divide & source of the Yellow river

View North in Washi country from Kun Chien La. The Hochu-Yalung divide & source of the Yellow river

“We followed the Matang river downstream, westwards, for just about 5 miles to a lamasery called the Maerk Kung Gomba, and then after a rest, turned up by a side stream entering a valley by a narrow passage between the hills - which, had it not been for the stream, we would have almost passed unnoticed. Then began a steady climb up the Ta Lung Chao valley which widened out and was cultivated in places. We crossed the divide between the Yalung and the Runga rivers by the pass called the Choh Tseh La (13,676 feet). From the top of this pass, far away to the north-west on a bearing of 120o, a high mountain peak could be seen standing out, in marked contrast to the rest of the mountain range of which it was the highest point. I concluded it was Mount Yabainkara, in the Bayantukmu range”.

“At about 4.30 we reached Ta Lung Chao (9,867 ft.), where we planned to stay the night. Just as we reached a bend in the road, about 15 men armed with Tibetan guns, and some with big thick long sticks came running down in their direction. The boy and the Muslim guide, Ah Hong, had gone ahead to arrange for our accommodation and had taken the rifle and shot gun - which they were deputed to carry - so we were defenceless. I asked the Tibetan boy what it meant, and it turned out that they were quite friendly and had been up in the hills hunting buck deer, of which they say there are a great number in the neighbourhood. I was glad it was nothing more serious”.

They passed through some villages and pushed on another mile to the last house up the valley, knowing that the following day they had to cross the pass and it would be strenuous day.

“The house we stayed at was a very tumbledown affair, inhabited by a blind man, his daughter and grandson. There was one room, the kitchen, with a wood fire, emitting volumes of smoke in the middle of the room. Outside the room, which, as in all Tibetan houses, was above the stable, there was an open shed for storing grass and straw. I decided to sleep there and got one of the tents slung up to close it in on the open side. It was quite comfortable though somewhat cold. I turned in to bed about 7.45 p.m.”

Day 124 November 19th, 1923 Ta Lung Chao to Ta Tsang Gomba - 20 miles

“A strenuous day. We were up at daylight, for although the muleteers had told me that we had only 10 li further to go than yesterday, I had doubts, which turned out to be correct”.

They travelled on up the valley, stopping on the South side of the pass for their midday rest. Then the boy and HGT, whilst the others were loading up, pushed on to the pass to get the boiling point and measure the altitude.

“At 12.50 we arrived at the pile of stones and prayer flags indicating the top. We had great difficulty in getting the water to boil. The wind was so strong it blew the lamp out time after time, and then there was too much oil in the lamp and it tended to blaze up. Altogether it took half an hour, but at last we succeeded and found the height – 13,676 feet. Leaving the pass, we descended through snow about 6 inches deep for a few hundred feet and then got clear of it and continued a gradual descent along the mountain side”.

The muleteers had evidently decided that they would not reach Ta Tsang Gomba, their destination and would camp out. It made no difference to them as they would sleep outside rolled up in their sheep skin coats. They crawled along at about 2 miles an hour and when urged to speed up, took no notice.

“At last I took my stick and hustled my pony into the middle of the pack ponies and whacked out. The ponies did not like the whacking and whenever I came near, they pushed along quicker. The pace improved nearly 50% and I told the muleteers. "We are going to make Ta Tsang Gomba tonight even if we have to travel by moonlight for the last hour or two"

The track followed the hillside and involved a descent of nearly 3,000 feet. In spite of everything, they still did not arrive till an hour after dusk, but there was a good moon, so they got on all right and after travelling just over 20 miles they reached Ta Tsang Gomba (about 11,000 ft.)

Day 125 November 20th., 1923 Ta Tsang Gomba

“I sent Ah Hong on ahead yesterday to fix up ponies for the next stage, so as to lose no time, but he was unable to do so as the head man was away - and not expected back for another day or two - so we are held up.

“It seems there is a real feud on between this place and Saan Kerh Doma, and all contact is suspended. As a result: nobody will hire their ponies to go through. As the headman was away, maybe for several days, we got in touch with one of the lamas and he tried to arrange for six more animals to make up our number to 15. If he can fix this we plan to leave tomorrow for a place called Chang Kwan Rum Reh, neutral ground, which is a roundabout way of getting to Saan Kerh Doma - and then we will need to change animals again. I hope this will get over the difficulty. Saan Kerh Doma is only 3 days from Sotsang Gomba, so it will be be a great step.

The headman's deputy turned out to be a rather crusty old chap, and when the boy went to see if the headman had returned, he practically ordered him out of the place saying "We can do nothing for a few days".

“The ponies which brought us here, I paid for on arrival, believing that we would be able to fix up things quickly. Being dismissed, they went off back with loads of salt and our retreat is cut off. As the whole place is clearly in the hands of the lamas, and they appear distinctly indifferent, and somewhat hostile, you can imagine the position.”

After HGT had paid them, the acting headman became very difficult. They could get no one who would provide them with more pack-animals, while the only shelter they could get was a shed where refuse was dumped.

“This is a lamasery with about two hundred lamas. The boy says that they have never seen a foreigner before and are very suspicious and worried by my presence. When I went out for a 15 minutes’ walk the lamas would appear in their doorways and call after me. The door of the lamasery temple is carefully kept locked whenever I go past.

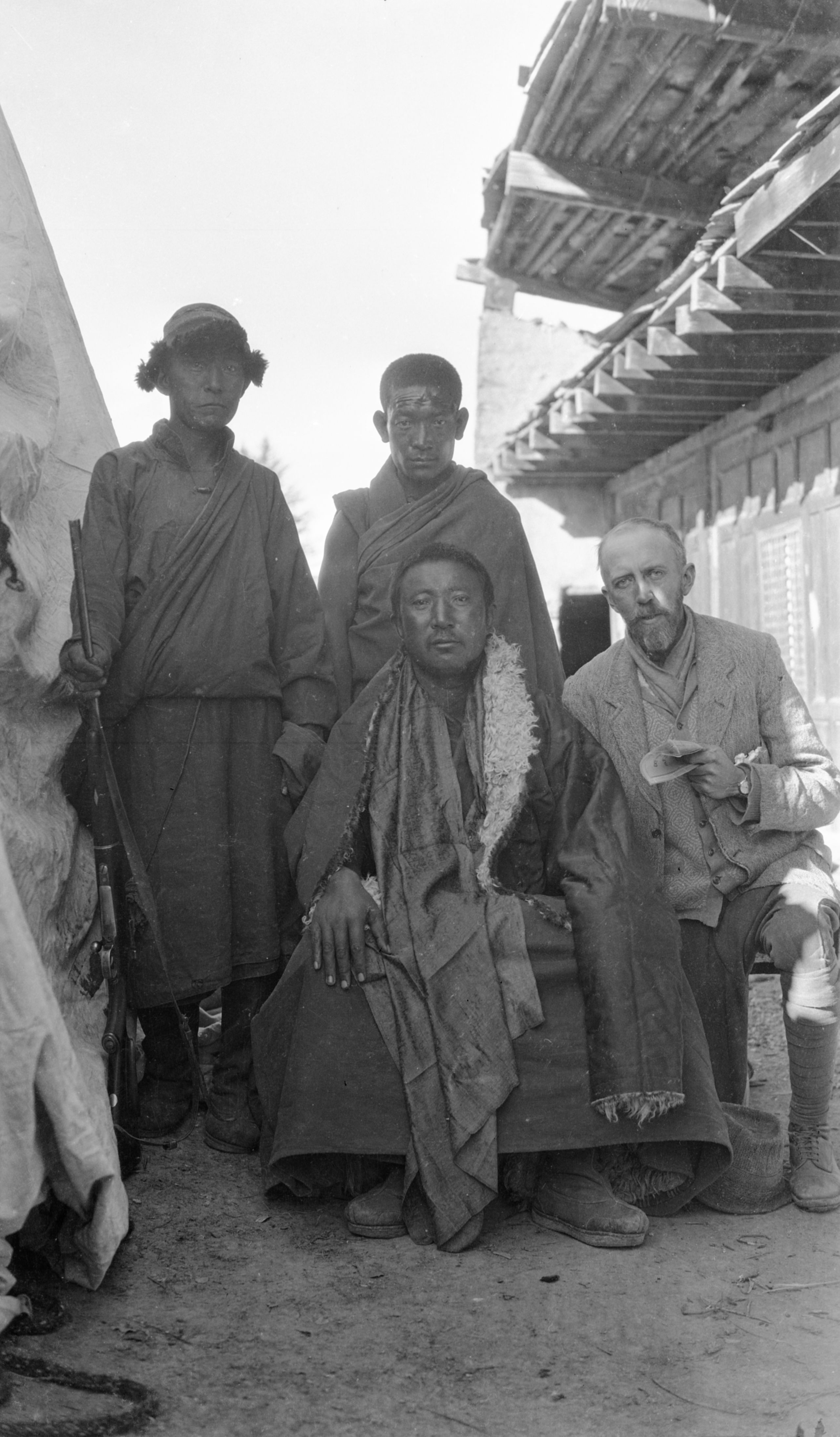

“Gradually by tact and courtesy, I became very friendly with the lama in whose house we are staying. He is the only one who is friendly and I have endeavoured to nurture the friendship with little gifts - a pair of small scissors, a couple of needles, etc.”

“This morning I have taken his photograph to his great satisfaction, and I have promised him a copy, so am hustling the development and printing. I wanted to take the picture in the courtyard, but he was afraid of the neighbours catching sight of him being photographed by the foreigners - so begged me to do it on the roof, where there was no chance of being seen. Having promised him a copy, I set about the development and printing”.

The Living Buddha (our host) and others with HGT at Ta Tsang Gomba

The Living Buddha (our host) and others with HGT at Ta Tsang Gomba

“Later our host’s messenger returned to say that the owner of the animals would be willing to go, but not until 3 days time, as they, the lamas, are all to be engaged in reciting special prayers until the 13th of their month – so we will have to stay here for three days”.

“The Tibetan boy has just come in to say that the owners of the yak and ponies are coming in at 12 o'clock to fix up the transport and say they must have the money paid in advance. I am going to offer them an extra amount if they will leave tomorrow”.

“Our friendly host lama thinks that there should be no difficulty at the next place as there should be plenty of animals, and quite easy to fix up. As a backup if necessary, I hope to arrange for the muleteers to bring us back if we cannot engage more animals etc, as I don’t want to be stranded out with the nomad tribes - whose home is a yak hair tent”.

Day 126 November 21st, 1923 Ta Tsang Gomba

“I had rather a restless night as I kept turning over in my mind the question of transport and how we are going to move on. The muleteers did not turn up as promised - so I gave the full amount of the hire money to our host and asked him to fix the matter. He accepted the money, as he had no doubt about their being all right”.

“The question remains, how are we going to get on from Rien Rerh to Sotsang Gomba, where we will be again on a caravan route and where there are no houses of fixed abode”.

“This morning before getting up I read the November 21st “Daily Light” and found great comfort. "It shall come to pass when he crieth unto me that I will hear for I am gracious".

After a tub and breakfast, the Tibetan boy arrived and said that their host, who turned out to be the next to the head lama, and himself a living Buddha, had of his own accord offered to send a servant with them for the next 2 days journey to Rien Rerh, so as to fix up the hiring of animals direct to Sotsang Gomba. The servant knew the tribes people at Rien Rerh and would be able to arrange things with them quite easily.

“What a relief!! Just what we needed, and now there should be no cause for anxiety. The boys both said that their lama host seemed to want to help them in every possible way. I was so glad that I had pushed through a print of the photo I had taken of our host, and also a very good one of the lamasery. I presented them to him with my best thanks for his personal help, and he was delighted. How I wish I could talk to him in his own language and tell him something of the Tao li - but all I could do was to leave him with a Tibetan copy of St. John's Gospel”.

Ta Tsang Gomba (north of Cherh-tsz)

Ta Tsang Gomba (north of Cherh-tsz)

They did eventually learn the cause of the feud and the block on the line which had only existed for a month. The people of Saan Kerh Doma had accused the people of Ta Tsang Gomba of having caused the death of their headmen by sorcery.

By going to Rien Rerh (2 days along the road) and then fixing up transport direct to Sotsang Gomba they sought to avoid Saan Kerh Doma altogether, and so get past the block. They hoped to reach Sotsang Gomba in a total of seven days, possibly 6, or even 5 depending on when their transport arrived. The road was said to be perfectly quiet - so now all was favourable.

In his journal HGT wrote:

“I just lift up my heart in thankfulness and realise again yesterday (November 20th) Daily Light promise – “I will bring them blind by a way they knew not, and I will lead them in paths that they have not known, I will make darkness light before them and crooked things straight. These things will I do unto them and not forsake them”. How true it has been – and it makes me feel ashamed of having had a restless night, and of worrying about things overmuch”.

“In the afternoon, after finishing my writing, I went out for a stroll along the hillsides, for Ta Tsang Gomba is situated practically on the top of a mountain ridge - There is a good path and I was out for about 1½ hours, walking all the time about the same level - with glorious views in all directions. Just as I arrived back it began to snow”.

Day 127 November 22nd, 1923 Ta Tsang Gomba

“In the morning there was three inches of snow on the ground. We are up at 10,000 feet so it is fairly cold at nights, but when the sun is out it is quite warm. It carried on snowing slightly all morning. I hope the sun will break through tomorrow and warm things up, for we are planning to leave soon after daybreak”.

“I had a chat with our host and friend the lama. He said his man would pass the word on to the fresh muleteers who will help us at Sotsang Gomba, where we will again change animals”.

“The houses of this lamasery are different to anything I have seen before; round the flat roofs of some is a wall, in which are included layers of brown reeds laid crosswise, and with ends cut off evenly - giving the appearance of a stucco. (GP had described this in an article in the Geographical Journal of March 1911, as occurring in the Labrang monastery, he had thought it was unique as he had never seen it elsewhere.) The roofs are of slate - irregular pieces, but giving the appearance of a slate roof in England”.

“Last night at about midnight the gongs of the lamasery were beaten, evidently to arouse the lamas for the day of devotion – Our host and friend had not been to the temple, and when I asked why, he told me it was only the lower order of lamas who had to go to read the sacred books. The more highly placed lamas - such as the living Buddhas had no need to go”.

HGT wrote in his journal:

“My wrist watch stopped this morning, so I have spent an hour and a half taking it to pieces and am glad to say it is going again now. For a week now I have just guessed the time - putting my watch at 6 a.m. at daylight - the exact time does not matter, so long as I can take the times on the road and so get the distances, and find how much more daylight we have to travel by.”

“Everything is now fixed up for our departure in the morning, and I am looking forward to getting on our way. We are now on the last tin of butter and have only 1½ tins of milk left, so if we do turn off on the Golok trip we will have to live the simple life. Fortunately, we still have plenty of the essentials - flour, sugar, rice, jam and a pound of tea, which I reckon could last at least 6 weeks by which time we ought to be at Lanchow where we can get stores. If we do not go via the Golok camp then I estimate that in 2 weeks’ time we should be arriving at Taochow - where there are missionaries of the C.I.M. who will help out with a few tins of milk to carry us over to Lanchow in comfort”.

Day 128 November 23rd, 1923 Ta Tsang Gomba to K’a K’a Roh - 4¾ miles

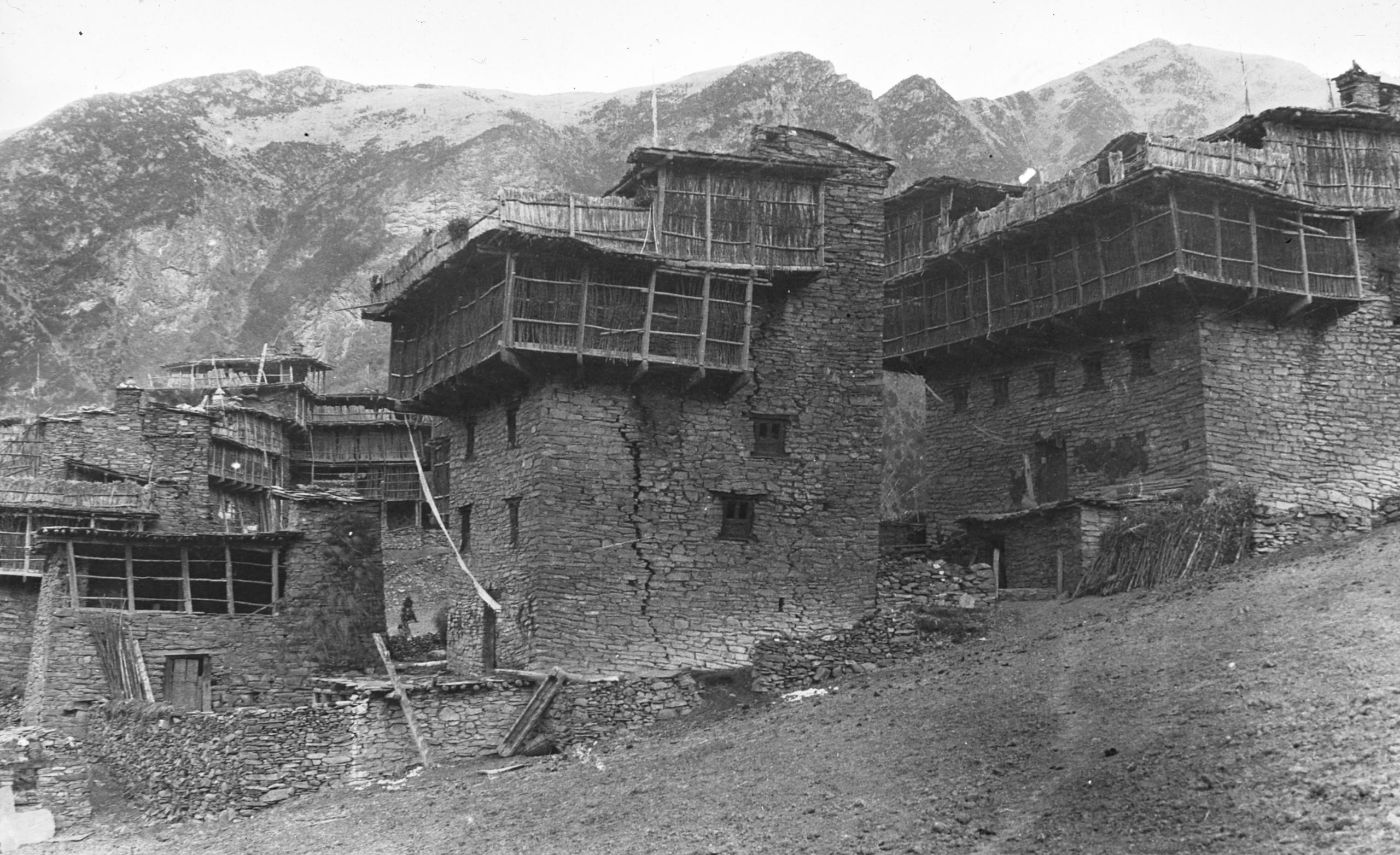

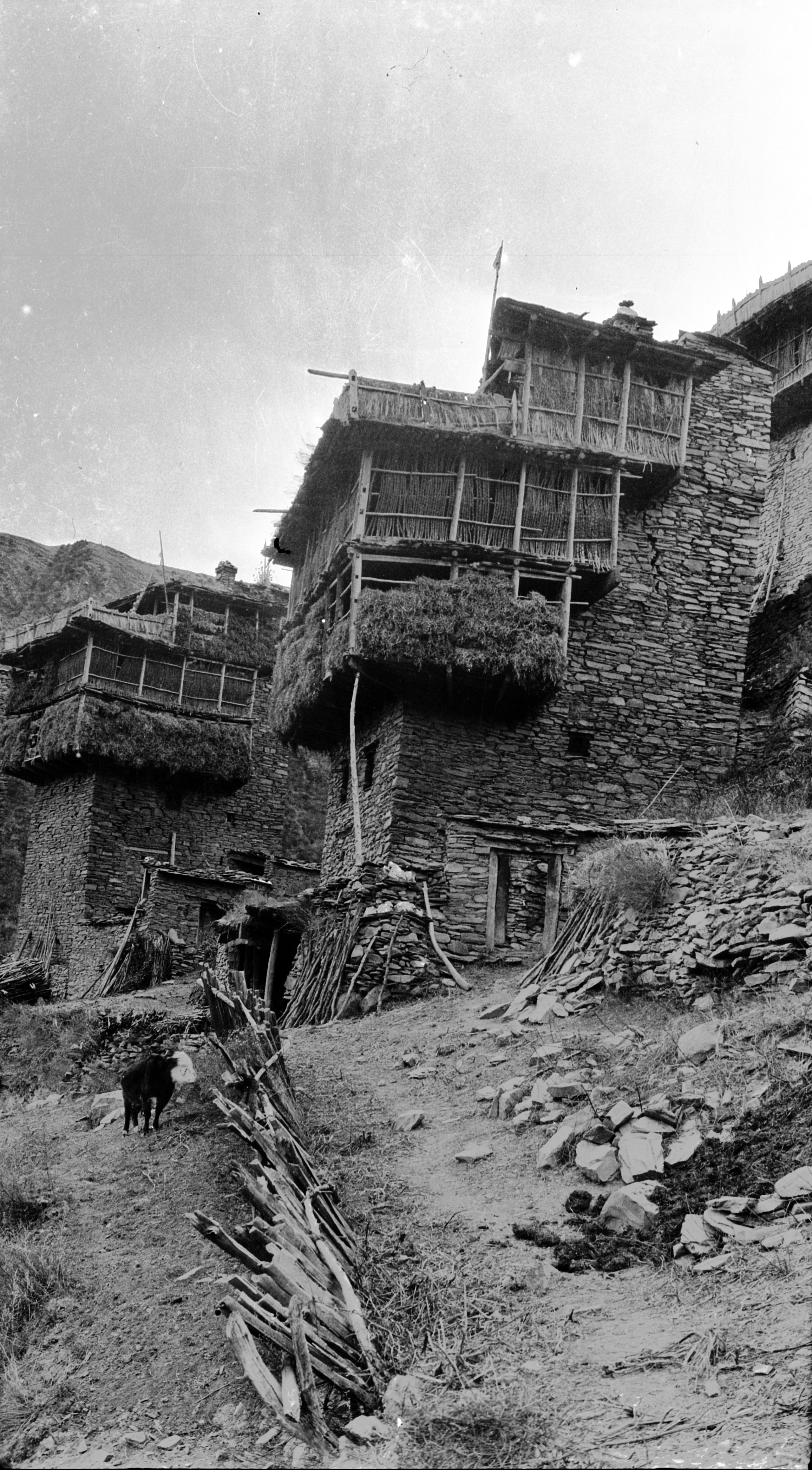

“We got off at last, starting at 11.33 a.m. I thought the yak would never turn up - as we were up at daylight so as to make a good start. At first only 8 yak and 1 pony arrived. After their host and friend, the living Buddha, had sent 3 messengers with no effect, he went himself, and soon the remaining 3 yak and 3 ponies appeared on the scene. We only made 4¾ miles as we stopped at the last house up the valley (10,755 ft.). The houses are very curious, they are mostly 5 stories high, having the appearance of a tower, the 2 upper stories projecting with a kind of veranda closed in with twisted reeds”.

Houses in K'a-ka-roh valley

Houses in K'a-ka-roh valley

“At first when we arrived no one would give us a place to stay, but shut their doors, and then watched us from their top stories or roof. At last we effected an entrance, but the landlady came and wanted to turn us out again. Finally, the Tibetan boy explained that we were friends of the living Buddha at Ta Tsang Gomba, and this worked. The old lady became quite affectionate and could not do enough for us”.

More houses in K'a Ka Roh

More houses in K'a Ka Roh

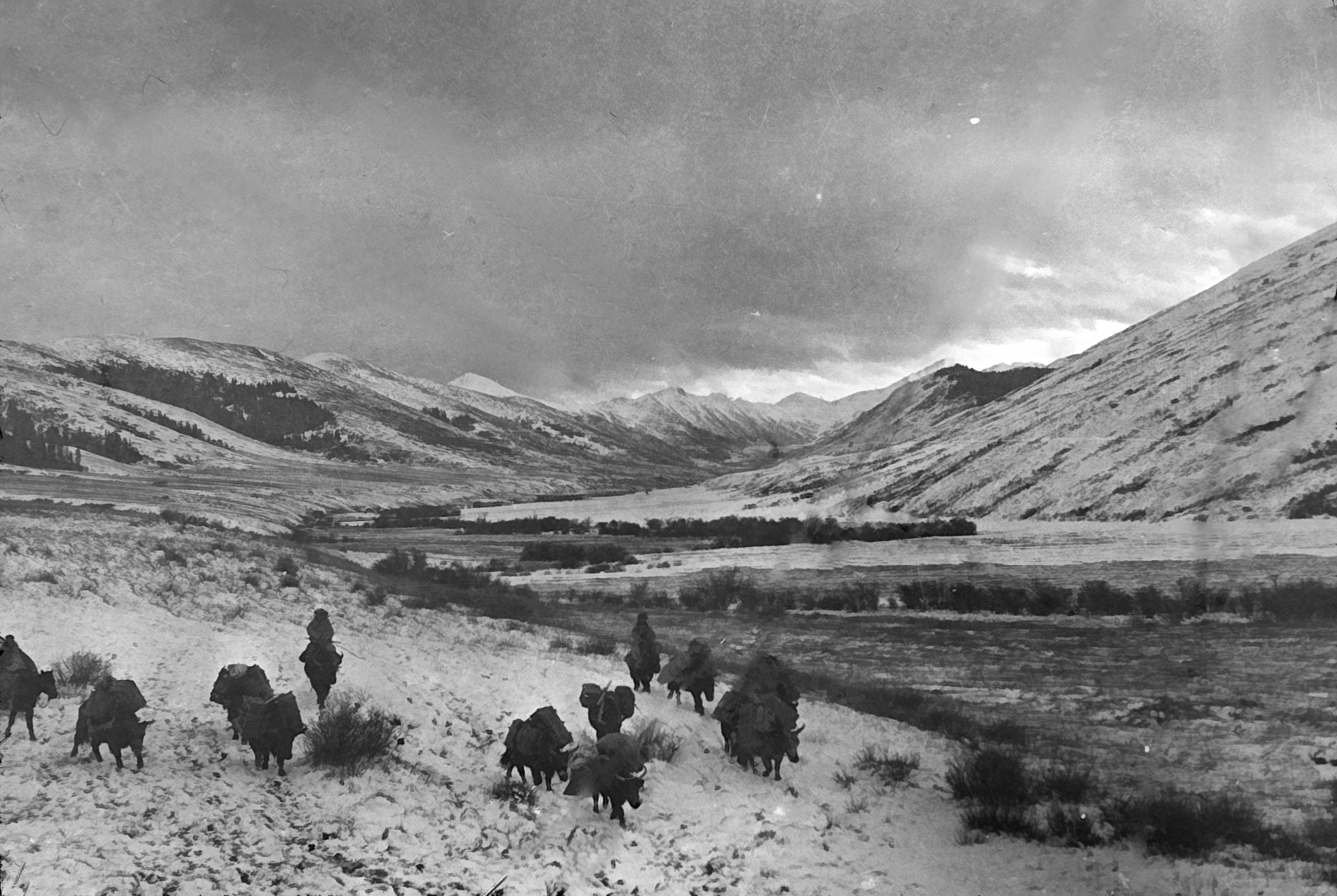

Day 129 November 24th, 1923 K’a K’a Roh to Chong Koh Rien Keh - 20¼ miles

“We made up for the short stage yesterday by a very long one today. We started out at just before 7 o'clock and did not get in till 6 p.m. - after dark, by moonlight. We had to get over the last high pass called the Kun Chien la, (13,298 ft.) which was part of the divide between the Yangtze and the Yellow River. Oh! It was hard work”.

As they reached the top it began to snow - and a strong driving wind made it bitterly cold. Although this pass was lower than several they had negotiated before, it was not easy, for driving snow made it difficult to see the track.

“We tried to get the boiling point but had to descend 300 feet before we could find a place where there was some slight protection for the hypsometer so that we could get the oil-lamp going, and even then, it took over ½ an hour”.

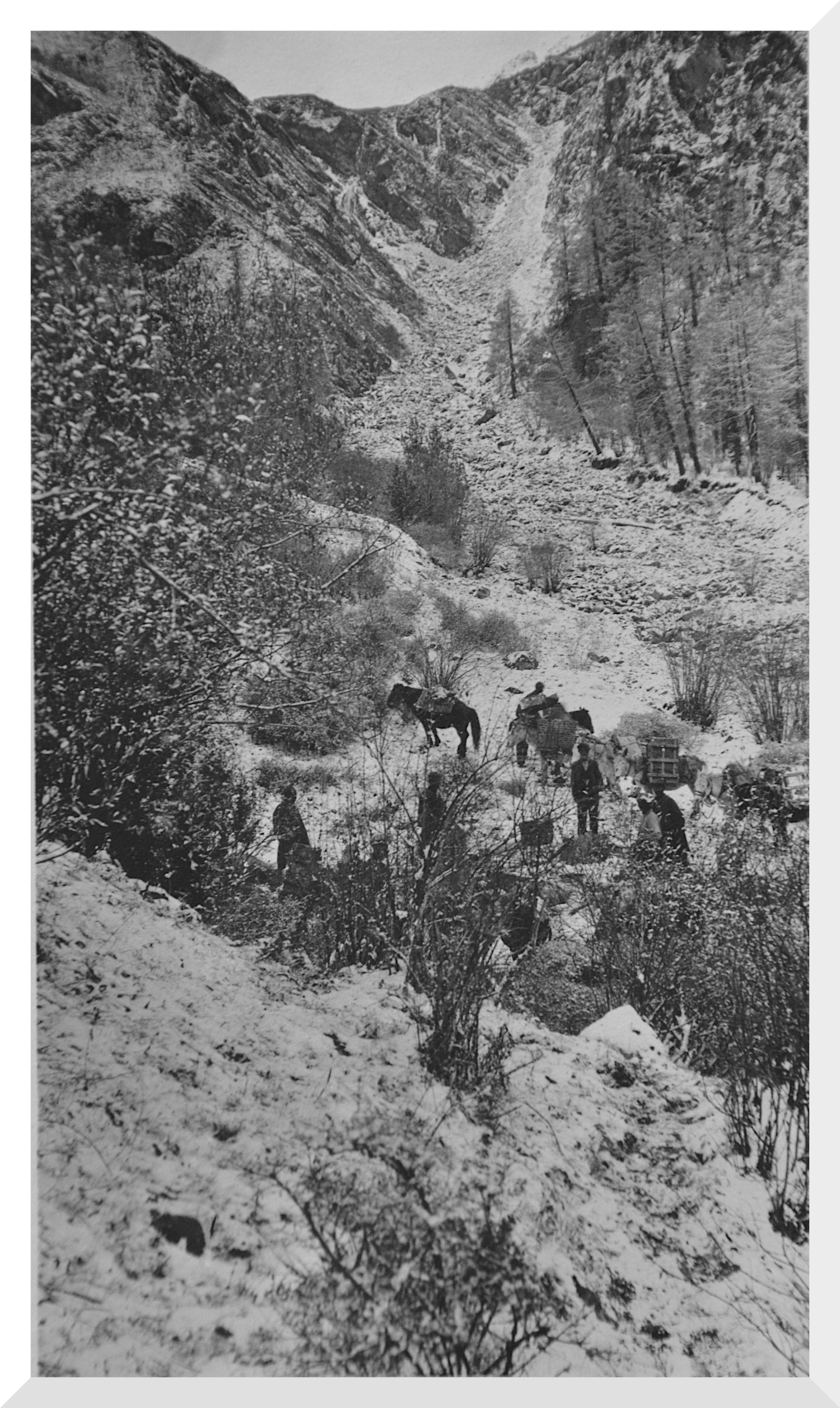

Yak transport near the Run rerh (white river)

Yak transport near the Run rerh (white river)

They crossed the top of the pass and descended a little farther and the downfall of snow ceased and the cloud lifted.

“A glorious view down a great valley burst on our view. No human beings or sign of life - just a great valley, the upper part entirely, and the lower part partially, covered with snow. We were glad to drop down and get out of the biting cold of the pass”.

“I sent the Tibetan boy and the lama's servant on ahead to see about transport for the next stage. When we arrived at the village of Chong Koh Rien Keh (11,312 ft.), we were met with the news that all was arranged for a further distance - not right through to Sotsang Gomba, but 2 days (2/5ths) of the way”.

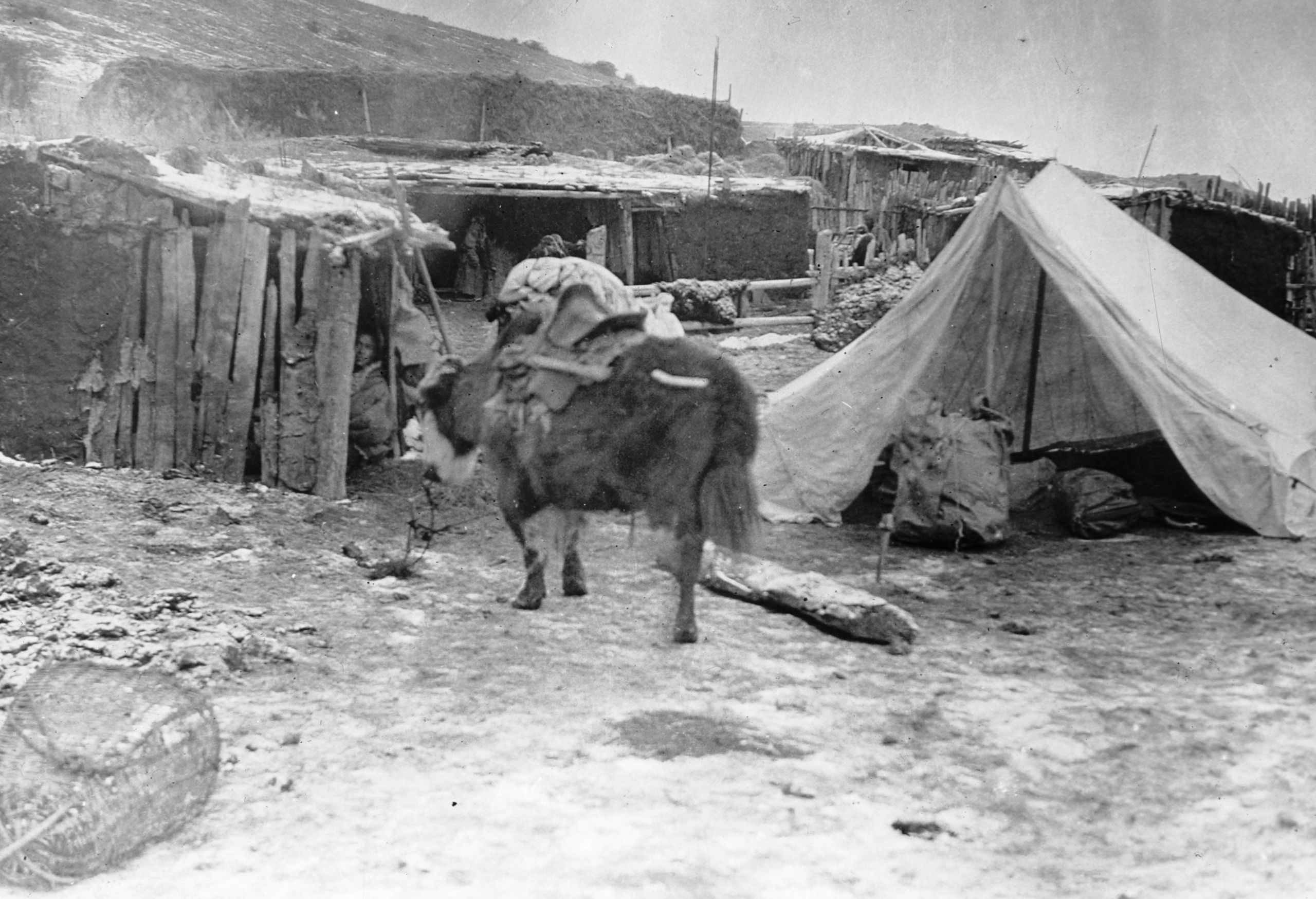

Their tent in the Tibetan village of Chong Koh Rien Keh

Their tent in the Tibetan village of Chong Koh Rien Keh

“This is a typical nomad village - mud huts with an enclosure made of rough logs - in which the yak can be turned in. Fuel is almost entirely dried yak dung. It makes a fine fire but requires the bellows constantly to blow it up. The people were apparently Goloks”.

“We were given the use of one of the huts and pitched a tent just outside. It was very cold, and I was glad to have my supper in the hut, and then get to bed quickly”.

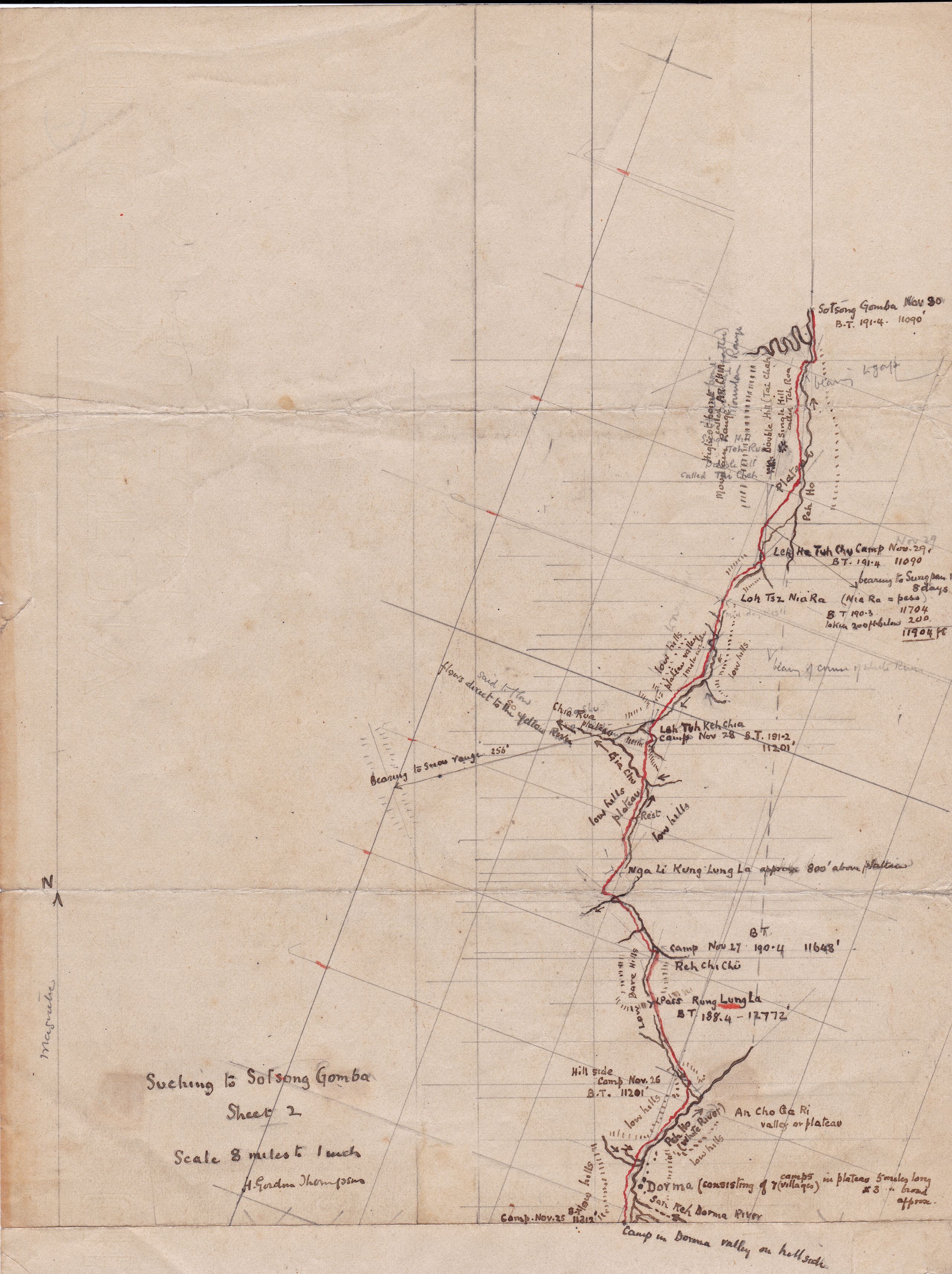

HGT’s hand-drawn map of Dorma to Sotsong Gomba

HGT’s hand-drawn map of Dorma to Sotsong Gomba

Day 130 November 25th, 1923 Chong Koh Rien Keh to the Dor Ma Valley - 15 miles

“The morning started with brilliant sunshine, although it is bitterly cold, and the ground is like iron. However, we have no pass to cross, and we were glad to set out. Chong Koh Rien Keh is situated on a plateau - splendid grazing land for yak, sheep and ponies. We followed the river which runs through the plateau, and soon it entered a narrow valley - running due North. No cultivation, simply grazing ground, where we occasionally saw some sheep or yak. We are now on the watershed of the Yellow River”.

“At 11 a.m. we stopped for lunch, but clouds came up and soon it was driving snow. We had a quick meal of bread and jam, and cocoa from the thermos, and then set off again. From our lunch place we ascended a valley and crossed a ridge, and now can look down into another plateau with the Peh Ho (White River) flowing through it. We had hoped to arrive at Dor Ma (or Tor Ma) but near to sunset found it impossible - so camped on the hillside (still at 11,312 ft.)”.

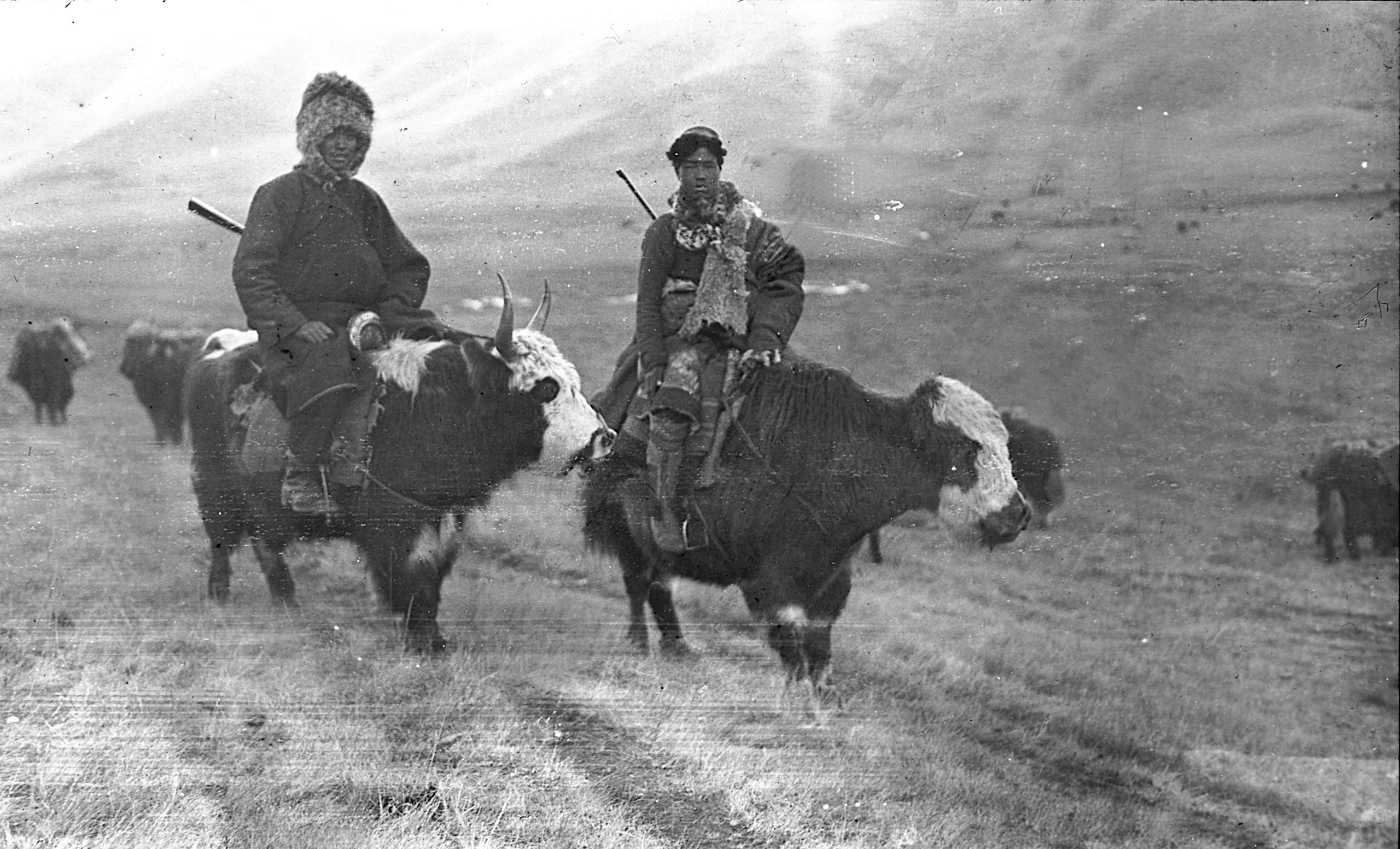

HGT travelling on a Yak in Golok country

HGT travelling on a Yak in Golok country

"We have our present yak and mules for one more day and then we will need to make fresh arrangements, but we have been told there will be plenty to be had at our next stop. The planned route is to follow the White River right down to the Yellow River, where at the junction was Sotsong Gomba. I reckon we will still have 3 or maybe 4 days journey".

The young Chinese "boy" and Tibetan "boy" on their yaks

The young Chinese "boy" and Tibetan "boy" on their yaks

“It is not quite so cold tonight though we are at the same altitude. Tomorrow we shall certainly be lower and so hope to warm up a little”.

Day 131 November 26th, 1923 Dor Ma valley to Au Chu Ka Ri valley - 11½ miles

“We have only made a short stage today, as we have arrived at the place to change transport. There is a lama staying here who is brother to a junior lama in the Living Buddha's household so that gave a sort of introduction, and the headman is off to arrange for yak and ponies. Thus, the way is being cleared for the last stage to Sotsang Gomba”.

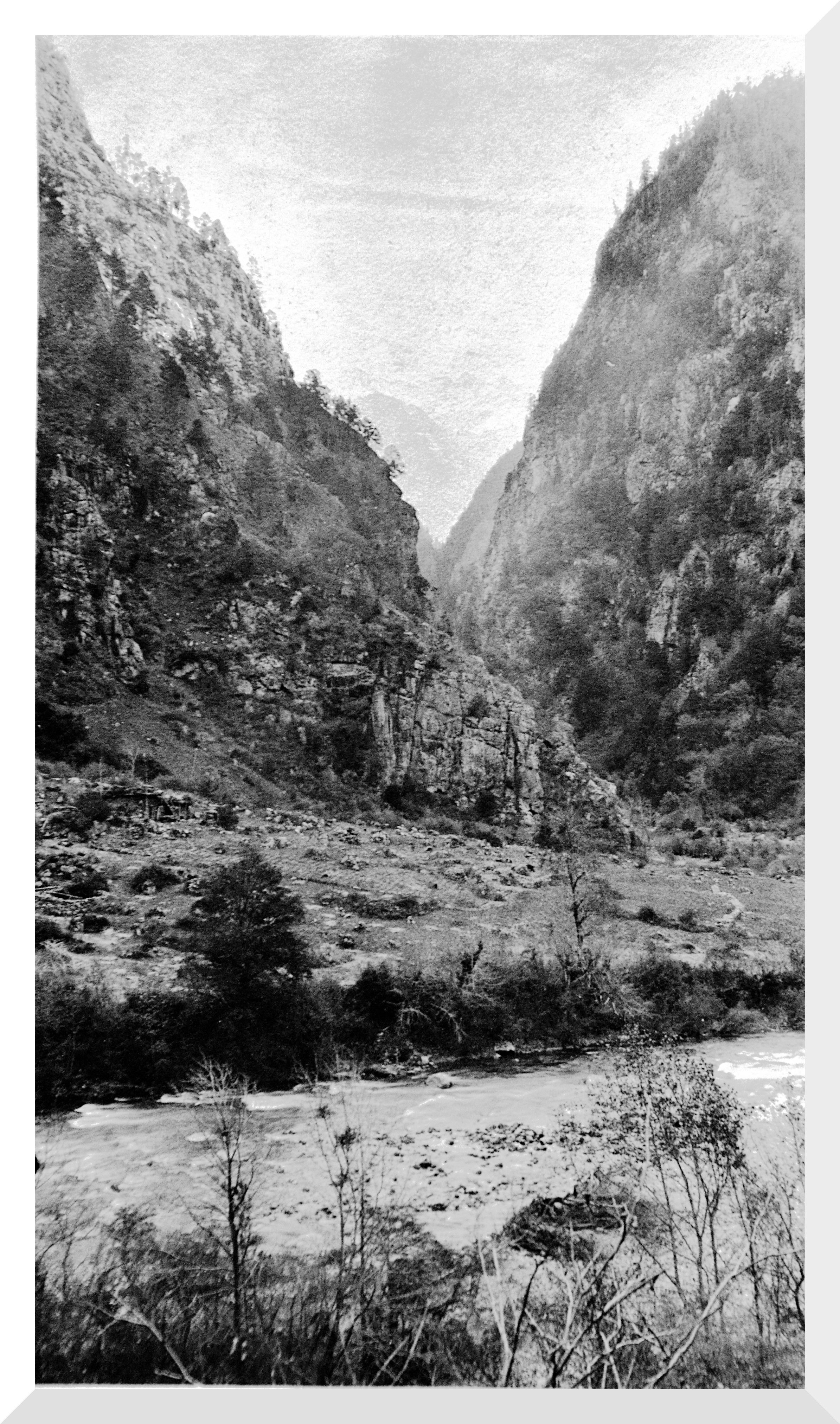

The White River looking North from near Ka-Ri camp

The White River looking North from near Ka-Ri camp

“For two days we have been following the White River, which is full of drifting ice, and flowing almost due north. Now, on the third day, after being augmented by numerous small streams the river is of considerable size, and its course is almost exactly northeast. In places the valley widens out into grassland and I counted seven camps or mud-hut villages, and there is splendid grazing for yaks, sheep, and ponies”.

The people here were apparently a mixture of Goloks and Ngaba, the Golok country being more to the west, the Ngaba more to the east, of the White River. A large proportion of the people were nomads with great yak-hair tents, but at intervals they came to groups of mud-walled homes which might by a stretch of imagination be called villages. These were associated with large stockades where the yaks and ponies could be herded, so that cattle raising seemed to be the one occupation of the people. They spoke a fairly pure Tibetan according to the Tibetan boy, who was readily understood. Fuel was almost entirely dried yak-dung

“In this particular camp at Au Chu Ka Ri (11,201 ft.) there are 10 tents arranged in a kind of circle next to the largest which is the head man’s tent. There is also a white tent with a square canopy supported by 4 poles – this is the Lama’s tent. Our own tents were only 100 yards away, but out of sight of the camp by reason of a hill or mound in the hillside”.

"I wanted to get a photo, and quietly made my way to the crest of the mound - only about 20 yards from their own tents”.

HGT wrote in his journal:

“Two great Tibetan mastiffs spotted me and came bounding along - with almost a roar. I had my thick stick, but realised that I could not defend myself both in front and behind. Fortunately, our Muslim guide heard and saw. He picked up 2 big stones and with two good shots he checked their rush while I retreated. I suggested going on the pony, but they all said "No, the dogs are very fierce and would not hesitate to attack a pony", so my snapshot was impossible.”

“The yak and ponies are now all fixed up to leave tomorrow”.

Day 132 November 27th, 1923 Au Chu Ka Ri to camp by Reh Cho Chu (river) - 10½ miles

“We did not get off till 9.48 as we have new yak and have to wait till they have arrived and are loaded up. Instead of following the White River the yak drivers insisted on going up the side valley in which we are camped, crossing a pass, the Rung Lung la (12,722 ft.) and then descending to the Reh Cho Chu, a little river which is a tributary of the White River”.

Looking South from the Rung Lung La Pass

Looking South from the Rung Lung La Pass

Looking North from the Rung Lung La Pass

Looking North from the Rung Lung La Pass

They were now in the eastern part of the Golok country, and their new yak-drivers evidently knew their countrymen fairly well, for one of them was invariably about half a mile ahead scouting. They would watch as his mounted figure made its way up a pass, and hesitate at the top while he dismounted and carefully peered over the top before he beckoned them on.

“On crossing the Rung lung La, a solitary horseman appeared on the hillside and then disappeared. A little later five armed mounted men entered the valley down which we were making their way and came rapidly towards us. The scout, who was quite close at the time shouted to them to stop and say who they were, but they took no notice and came rapidly on. I got out the two revolvers, and the boys had their guns, (shot gun and rifle). However, we waited and at last they turned up and turned out to be friendly, but they report a band of thieves about a mile further on, just beyond the next bend of the valley. So we decided to turn up a side ravine, where we could conceal ourselves. We decided to camp in a quiet spot by the river (11,700 ft.) till the following day, when the riders expect they will have moved off”.

The tent was not put up till dark and they made ready for visitors with a watch being kept through the night, in turns, by the boys.

“Pereira’s maps and my maps up to date, and my photo negatives and list of photos I am carrying on my person - so if we lose other things I hope to preserve these. Unless the thieves take my sports coat, which I am wearing, which by the way is in holes! We have just had prayers and committed ourselves to His keeping – who cares for His children. I have so much felt that we have been guided on the journey that whatever happens must be right. So, we break camp before daylight and go forward trusting in Him”.

Day 133 November 28th, 1923 Reh Cho Chu to camp in Lok Tuh valley - 19⅓ miles

“We all had a somewhat wakeful night and were up before daylight so as to get off before other folk were about. I slept a few hours with all my clothes on - ready for any emergency. However nothing happened I am glad to report. After the start which was made in bitterly cold weather - one of the muleteers, who by the way had a 12 ft. long pole like a lance, went on, scouting. The robber band had evidently moved on as expected, and although we passed a place where a man was robbed yesterday, we saw nothing”.

“The day's journey can be described as a series of plateaus, varying from 5 miles by 2, to 2 miles by ½ mile wide - with a small river running through the centre of each. Mile after mile of low hills is the characteristic of the countryside. No trees just bare hills, mostly blackened by grass fires, but excellent pasture in the valleys. The only sign of life was one lizard and the birds on the carcase of a dead yak. We saw no living person all day - but at one place, turning a corner of a hill we saw on the hillside, a square of prayer flags and streamers, and underneath the remains of a corpse put there to be eaten by the vultures, after the Tibetan custom, with this difference - the Tibetans cut up the body, while the Goloks put it out intact”.

The landscape after leaving Rung-lung-la with a corpse on the hillside and a vulture flying overhead

The landscape after leaving Rung-lung-la with a corpse on the hillside and a vulture flying overhead

At midday they passed out of the valley. That evening they camped in a lonely spot by a small river called the Gia Chu, in the Loh Tuk valley (11,201 ft.) which the guides said flowed into the Yellow River direct.

“On arrival at our camp, two people came over the crest of a hill. After looking at us, they disappeared again. Then 3 others appeared, mounted on yaks or ponies and seeing them our Tibetan boy said, "They are all right, thieves are always mounted on ponies". One of the muleteers and Ah Hong, our Muslim guide, went to investigate, but they moved off. I certainly feel more comfortable tonight in my mind and do not anticipate trouble. I reckon that we have only about 25 miles as the crow flies to go to Sotsong Gomba - but this will take us a day and a half - so we shall not get in till the day after tomorrow.”

They did not anticipate trouble but set a watch. Two large grass fires were raging close to our camp, so the Tibetan muleteers fired the grass around the camp so as to keep the bigger fire from reaching them.

Day 134 November 29th, 1923 Lok Tuh valley to camp by Leh Ha Tuh Chiu - 11¼ miles

“We posted a sentry that night, but although nothing happened the guides urged us to be on the move in the morning as soon as we could see. So we struck camp in the dark and were a mile or two on our way by daybreak.

“Throughout the whole day we only saw 2 people - with their horses up one side valley. There was plenty of traces of summer grazing camps and many herds of gazelle (one of 18) on the hill sides, and down by the streams. The boy tried two shots, with no result, except that all the gazelle disappeared!”

The descent down towards the White river nearing Sotsong Gomba

The descent down towards the White river nearing Sotsong Gomba

“After crossing the river we have camped at Leh Ha Tuh Chiu (11,090 ft.) only a day's journey from Sotsong Gomba. On two occasions we had an alarm of attack, but we displayed the fact that we are armed and were not molested. It is very cold at night, but when the sun is out the days are nice and warm. I expect to drop several thousand feet tomorrow , so the nights should get a little warmer”.

Day 135 November 30th, 1923 Leh Ha Tuh Chiu to Sotsong Gomba - 14 miles