Travelling the Tibetan and Mongolian Borders in 1923 - Part 2 Yunnan and Sichuan

A journey of exploration - a doctor's story - Part 2

This is Part 2 of an account of the journey from Yunnan-Fu (Kunming) to Peking (Beijing) that my grandfather Dr Hubert Gordon Thompson (HGT) undertook in 1923 in the company of Brig. Gen. George Pereira.

It has been compiled from the letters and journal of HGT written during the journey and from the lecture “From Yunnan-Fu to Peking along the Tibetan and Mongolian Borders” given by HGT to The Royal Geographic Society on 23rd November 1925

I have also drawn from the journal records of GP that were compiled by Sir Francis Younghusband in the book “Peking to Lhasa”; published by Constable and Company ltd. in 1925.

This second part of the journey was from Likiang (Lijiang) in Yunnan Province to Batang (also known as Xiaqiong ) in the Province of Szechwan (now referred to as Sichuan)

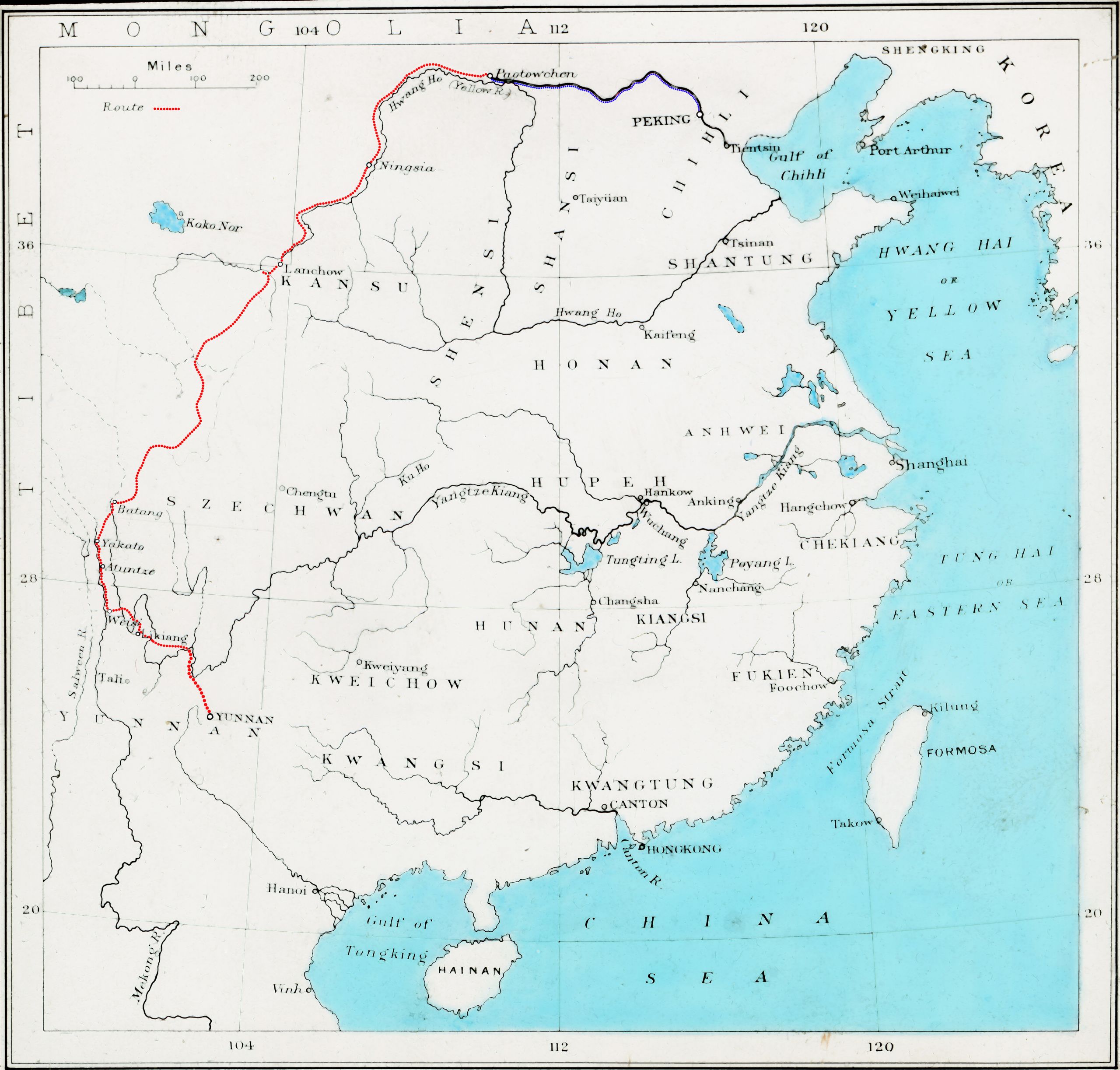

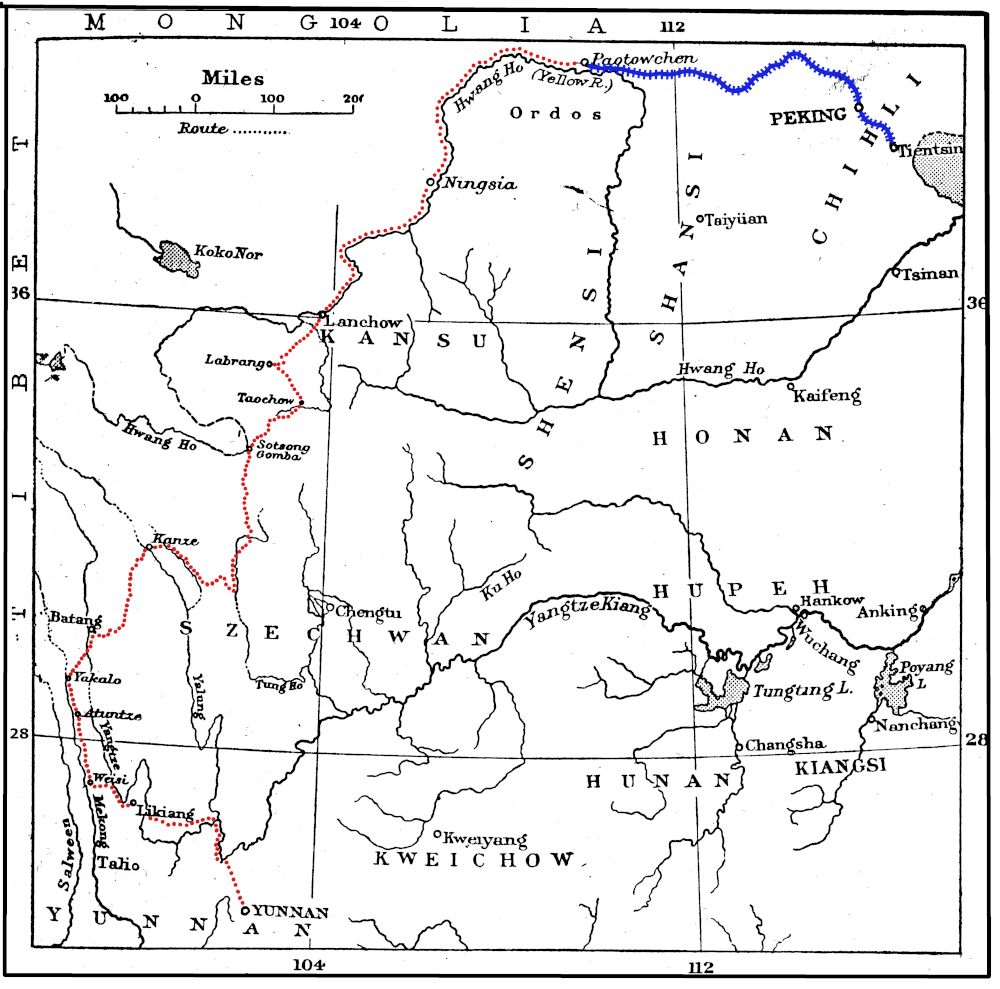

Click on the map above to dee the route taken from Likiang to Batang on a 1922 map

Click on the map above to dee the route taken from Likiang to Batang on a 1922 map

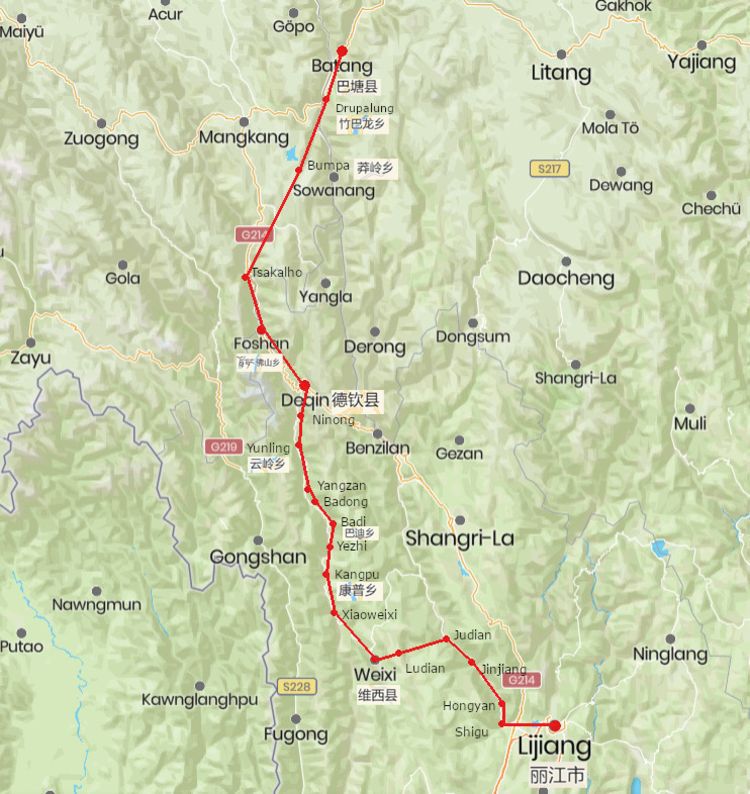

Modern day map of the route from Lijiang to Batang

Modern day map of the route from Lijiang to Batang

Day 27 August 12th 1923 Likiang

(Note: Likiang Fu (Lijiang) was one of the big stages on their northward journey. It was the old Mosuo capital, and inscriptions relate how, nearly four hundred years ago, the Mosuo king drove back the Tibetans, who were encroaching on their territory, and established themselves right along the valley of the Mekong).

"Likiang (now written as Lijiang) is an unwalled city of some 30,000 inhabitants, (7,561 ft.), and GP made the distance we have travelled from Yunnan Fu to be 872 miles. Many pessimists at Yunnan had said that we would not be able to get through in the rainy season. The roads have certainly been very bad, but not worse than in other parts of China. And though there has been plenty of rain, it fell chiefly at night".

"Behind the city to the north, rise great rocky, peaked mountains running north and causing the great bend in the Yangtze. They are partly snow-covered, and are the highest we have yet seen in Yunnan. GP estimated them at 17,000 feet".

"At the Li Kiang Post Office, we learnt the Telegraph line was broken, however it was repaired by the next morning. So, we are able to wire home as well as post letters".

"I have spent time here seeing patients, taking photos and developing 3 rolls of films. Sadly, the first lot were hardly any good. I hope for better results with a further 5 rolls".

Mo-su women at the market at Likiang

Mo-su women at the market at Likiang

"There are a number of different tribes-people in Likiang. The Mosuo, or Na-shih as they call themselves, which means black people, are found right up the valley of the Mekong and in the country round Likiang".

"The Lisu tribes-people are more aboriginal in character. Driven up to the hills, they inhabit pretty much the same region, but are scattered in the fastnesses of the mountains. In addition, there are Loutze, and La-ma-jen, with an infiltration of Tibetans from across the frontier".

Two Mosuo women

Two Mosuo women

More Mosuo women (Na-Shih) at Likiang

More Mosuo women (Na-Shih) at Likiang

“There being a festival, crowds of Mosu girls had collected. Many were walking together like in a girls' school: others were sitting out. The girls were in parties and the boys were separate. I was interested to notice the presence of cowrie shells, especially among the Lisu people. On inquiry I learnt that they had come from Burma and India; that they were valued at 100 to the Chinese tael, were sometimes used for barter, and were largely used for decoration of the headdress of the girls, being looked upon as a kind of dowry”.

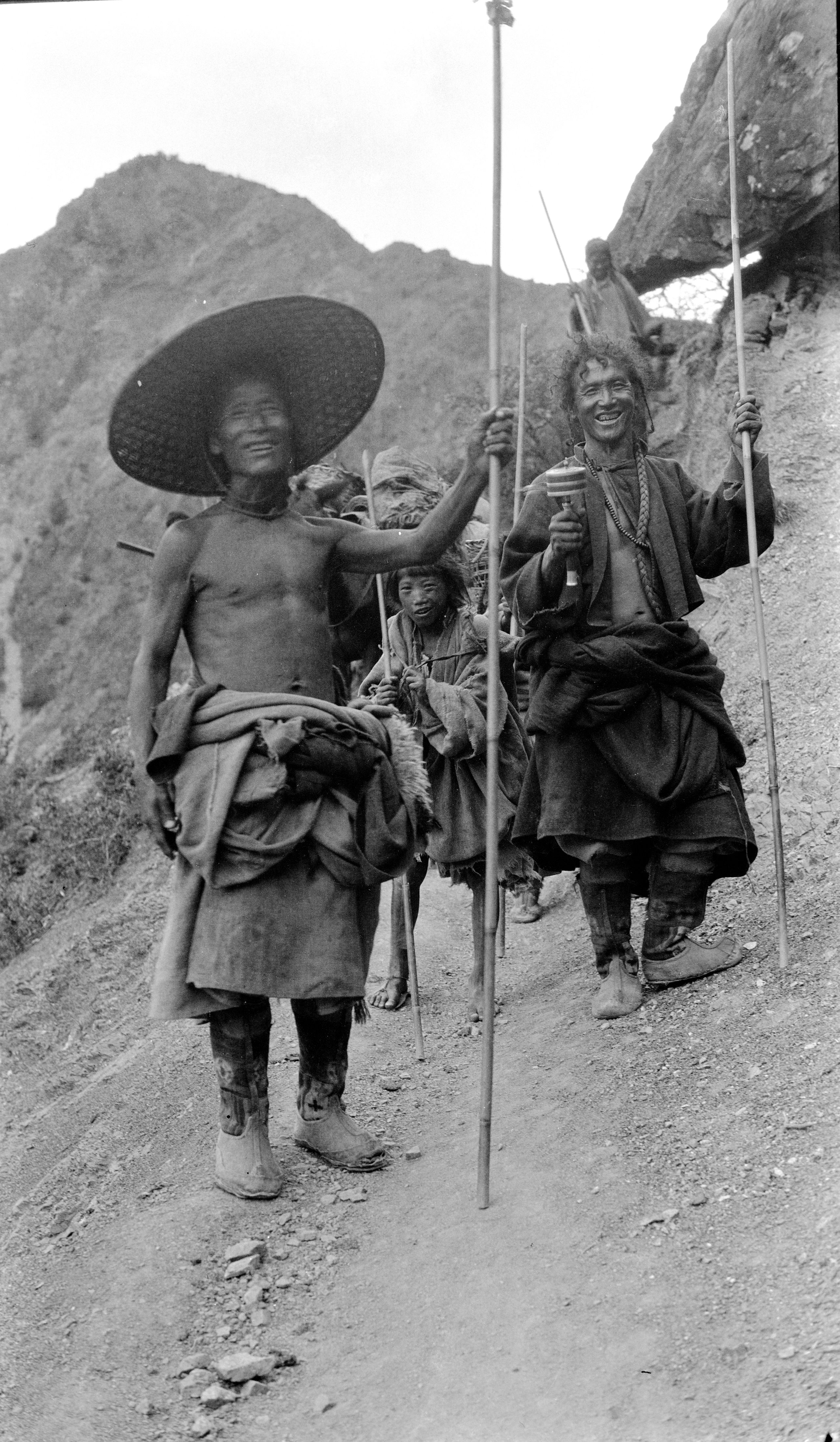

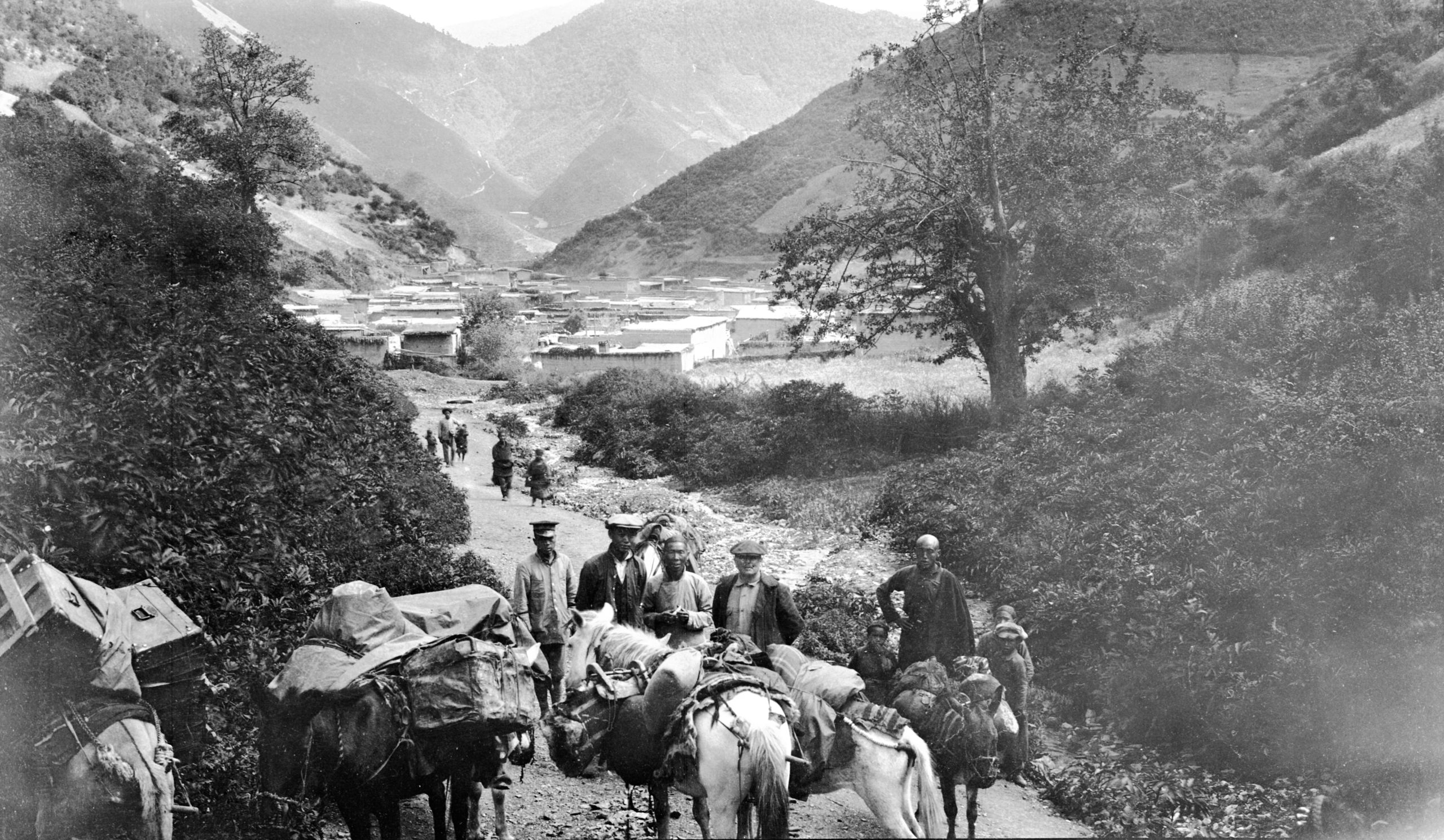

“At the city, we engaged Tibetan muleteers for the next stage of the trip; three weeks' journey to Atuntze. The lead muleteer was an old Tibetan, a most picturesque old fellow, with a big ear-ring in one ear, a broad hat and Tibetan dress, He spoke Chinese, and instead of $1.40 per day the mules were to cost 40 cents”.

The Tibetan muleteers preparing the midday meal - butter tea Tsamba in churn with ladle on top. The lead muleteer is on the right with large earing

The Tibetan muleteers preparing the midday meal - butter tea Tsamba in churn with ladle on top. The lead muleteer is on the right with large earing

“I wish you could see our Tibetan muleteers. There are four of them and they wear charms wrapped up in a kind of hair cloth round their necks, as well as a chain of beads; a big silver ear-ring in the left ear; a pigtail wound round the head; skin of face and body like tanned leather; a rough belt round their hemp clothing and suspended from it a sheath knife, ornamented with silver - a great metal pipe, a tobacco pouch, a flint and steel etc.”

Day Twenty-four August 9th,1923. still at Li Kiang

At Li Kiang great excitement had been caused in the city by the capture, twenty-two days previously, of Mr. D'Arcy Weatherbe, an English engineer, by Chinese bandits at a place two stages south-west. He had been trying to reach Batang from Burma and was making his way back to Yunnan Fu along the main road. They felt thankful that they had come by their unfrequented route, and so missed the robber band. The bandits’ condition for the release of Mr Weatherbe was that they should be reincorporated into the army.

GP liaised with the local Magistrate and suggested that the bandits' demand for reincorporation into the army should be complied with, while insisting on Mr. Weatherbe's immediate release.

“After careful consideration, we have decided that Mr. Weatherbe's capture need not affect us as he was to the S.E. and our road now is to the N.W, and if we hear of any difficulty ahead, up beyond Ya Ka Lo, we will probably get to Batang - via Tibet - GP was not for running any risks, but if there is trouble ahead we will endeavour to avoid it”.

Day twenty-five August 10th & 11th 1923 Still at Li Kiang

In a letter home HGT said:

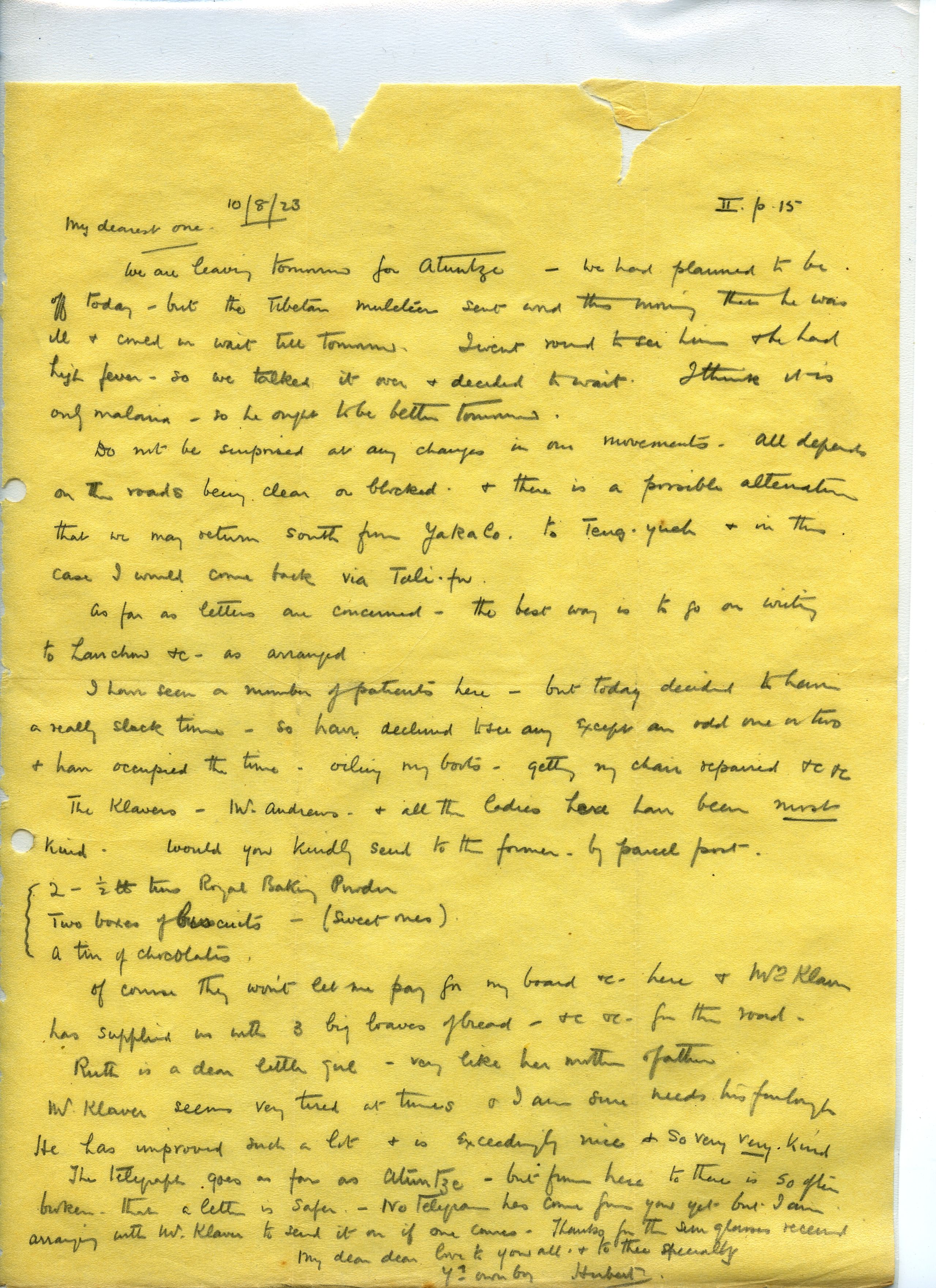

10 August 1923

My dearest one,

We are leaving tomorrow for Atuntze - we had planned to be off today, but the Tibetan muleteer sent word this morning that he was ill and could we wait till tomorrow. I went round to see him and he had high fever, so we talked it over and decided to wait. I think it is only malaria, so he ought to be better tomorrow.

Do not be surprised at any changes in our movements - All depends on the roads being clear or blocked, and there is a possible alteration that we may return South from Yakalo to Teng-yueh and in this case I will come back via Tali-fu.

As far as letters are concerned, the best way is to go on writing to Lanchow etc., as arranged.

I have seen a number of patients here - but today decided to .have a really slack time, so have declined to see any except an odd one or two and have occupied the time oiling my boots, getting my chair repaired etc., etc..

The Klavers - Mr. Andrews and all the ladies, have been most kind. Would you kindly send to the former, by parcel post:-

2 ½ lb tins Royal Baking Powder

2 boxes of Biscuits (sweet ones)

1 tin of Chocolates.

Of course they won't let me pay for my board re. here, and Mrs. Klaver has supplied us with 3 big loaves of bread, etc., for the road.

Ruth is a dear little girl - very like her mother and father. Mr. Klaver seems very tired at times and I am sure needs his furlough. He has improved such a lot and is exceedingly nice, and so very, very kind.

The telegraph goes as far as Atuntze, but from here to there is so often broken that a letter is safer. No telegram has come from you yet, but I am arranging with Mr. Klaver to send it on if one comes.

Thanks for the sun glasses received.

My dear, dear love to you all, and to thee specially.

Yr own boy,

Hubert.

Stage 2

Day twenty-seven August 12th, 1923. Li Kiang to Shi ku - 14 miles

They left Likiang at 8.30 a.m. after the few days' rest, and travelled 9 miles to Chi Li Tsun (Chi-L'o-ts'un). The road led across the plain and round the La-shih-Shui Lake They reached - Lau Shiu Ku, where they halted for lunch at 12.30 noon. It was just at the beginning of the descent to the Yangtze.

The plain around the La-shih-Shui Lake Looking N along E part of Yang-tze

The plain around the La-shih-Shui Lake Looking N along E part of Yang-tze

At 2 p.m. they set off again and went steadily down to the great river.

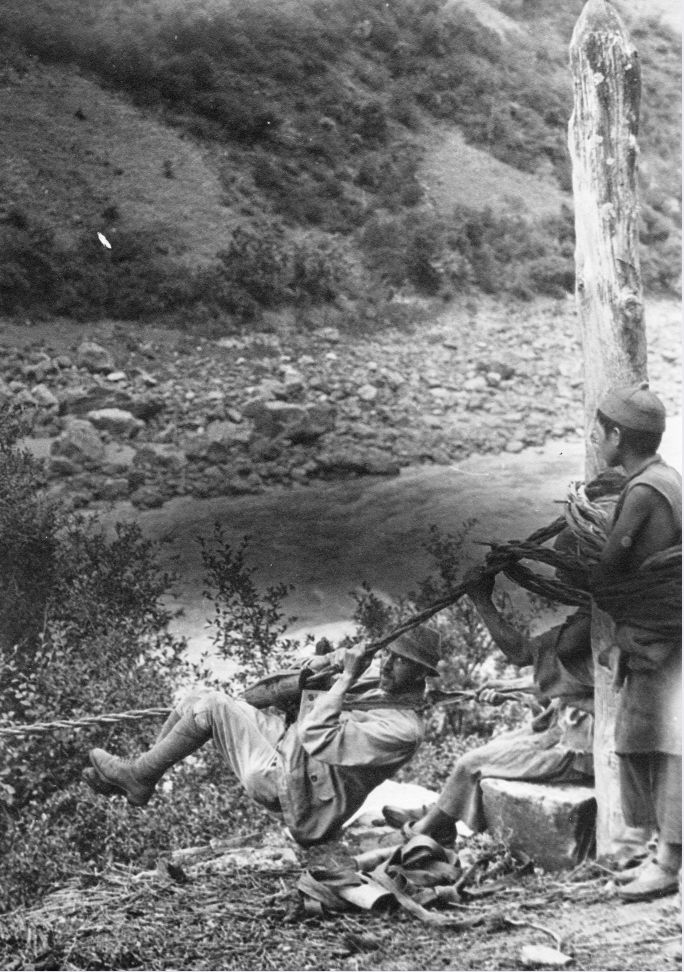

Ascending through woods between Lu-tien & Li-ti-ping. Escorts with crossbows

Ascending through woods between Lu-tien & Li-ti-ping. Escorts with crossbows

“We crossed the divide between the Yangtze and Mekong by Litiping - a beautiful little plateau about 5 miles in length, carpeted with flowers, with pine woods along its border and great flocks of sheep grazing on the pasture land. As we ascended through the woods between Lu-tien & Li-ti-ping we found “hanging hair” lichen called Usnea Longissima (also known as Methuselah’s beard) - a network of thin hair-like fronds that draped over, hanging from branches. In this area it grows mainly on oak. The escorts are carrying crossbows”.

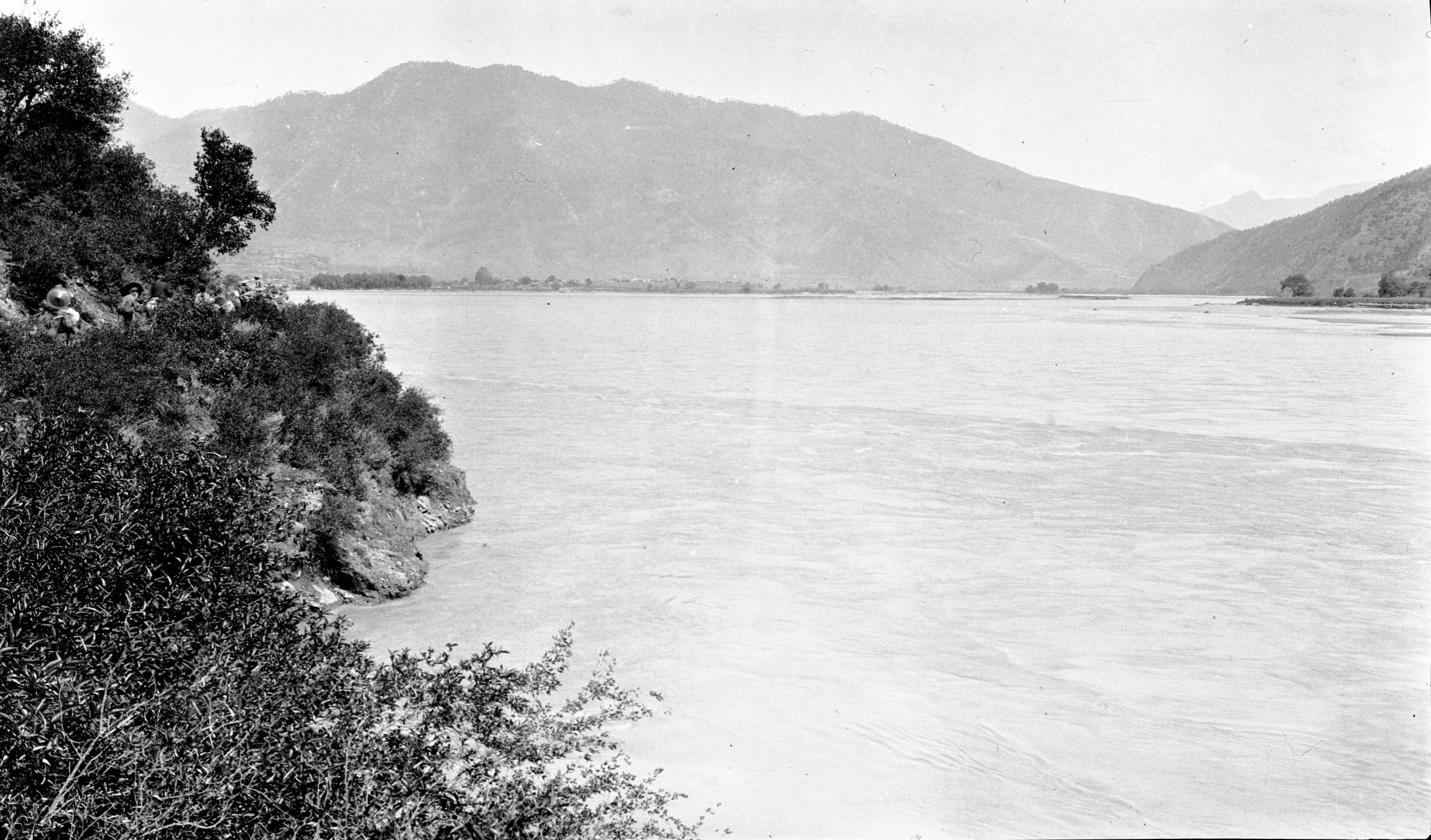

They followed the right bank of the river, travelling West. This is marked on the map just at the place where the Yangtze, here called the Chin-sha-Chiang, gave a sharp bend. The river was in flood and the whirlpools looked tremendously powerful. At one spot all the ponies had to be unloaded to pass a landslide. This of course meant delay, and they did not reach Shia ku till 5.30 p.m.

Shia-Ku at extreme Southern point of Yangtze bend

Shia-Ku at extreme Southern point of Yangtze bend

Shia Ku (5,900 ft.) 100 feet above the river, has two hundred families. It stood on a small hill, and had a great stony crag behind it.

“The weather is now quite chilly at night, and even in the day, only hot for a short time”.

The Yangtze at the Chi-tien bend

The Yangtze at the Chi-tien bend

Day twenty-eight August 13th, 1923. Shia ku to Hsia Kai Tzu - 19 miles

They left Shia ku at 7.30.

Looking up the Yangtze (south to north) near to Shia Ku

Looking up the Yangtze (south to north) near to Shia Ku

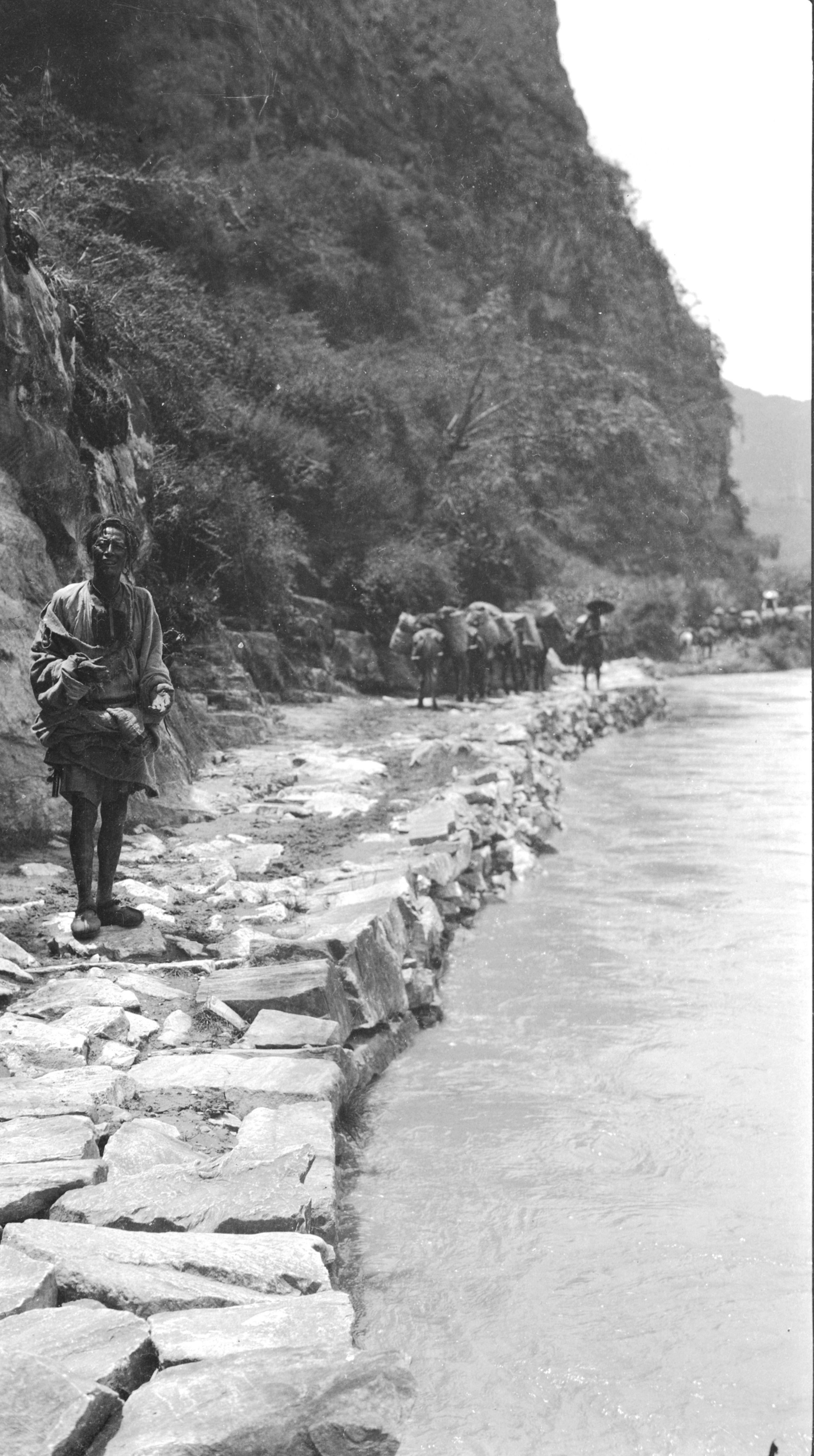

Road just above the Yangtze between Shih-Ku and Hsia-Kai-Tzu

Road just above the Yangtze between Shih-Ku and Hsia-Kai-Tzu

The day’s journey might be divided into three parts - each about 20 li.

“We travelled on foot, following the River bank of the Yangtze - the river was in flood, and in many places the road had been covered but evidently the water had gone down and was a few inches below the road level. We first passed through the village of Mu Chi Ti. As we neared Shia Ku we passed by a temple on the road (Fig. 9). Then just before reaching Shan Shia Ku we passed under a huge vertical cliff of rock, rising about 500 feet straight up. The road being practically cut out at its foot - A wonderful road!!”

“Hello - here are folks for medicine. I generally see a few each day after arrival and a cup of tea - must stop!”

Road by Yangtze

Road by Yangtze

From Shan Shia Ku they they walked on to Hsia Kai Tzu (6,041 ft.) which in total was just over 19 miles. Hsia Ke Tzu had seventy-five families and at an elevation of 6,041 ft. The villages about were a good deal scattered, and sometimes broken up into two or three clusters.

Day twenty-nine August 14th, 1923. Hsia Ke Tze to Wu Luh Ting (or Tien) - 17¼ miles

Two soldiers were sent to overtake them to advise that they went by the main road through Wei sheh to Atuntze. They had wanted to go on the smaller road via Peng-tzu-ya because there had been less landslides, but in view of this official advice, GP decided to follow the main road.

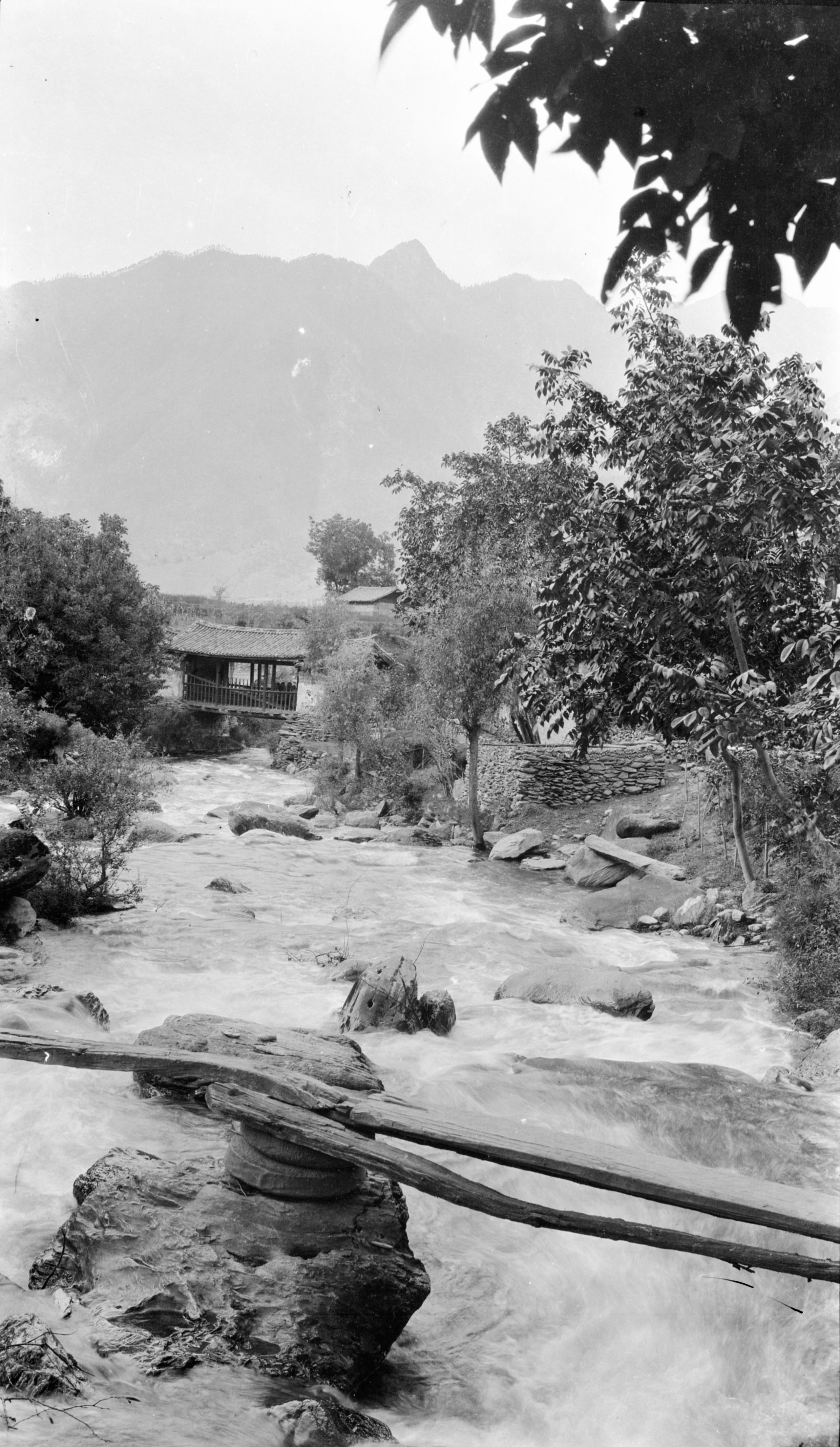

Bridge & falls at Hsia-Kai-Tzu

Bridge & falls at Hsia-Kai-Tzu

“We left Hsia Kai Tsu at 7.30 a.m and have had another day by the side of the Yangtze - following the river bank, travelling North and later on slightly West. It has been a glorious day, and we have come 17¼ miles - again I walked all the way, so you can tell I am in good condition.

“We rested at a place called Ch’iao Tuh, resting from 12 to 2 p.m. We bought some river fish - very like carp - not at all bad eating. It is fairly warm in this valley, and I hope to develop a photograph or two as soon as the sun gets down a bit”.

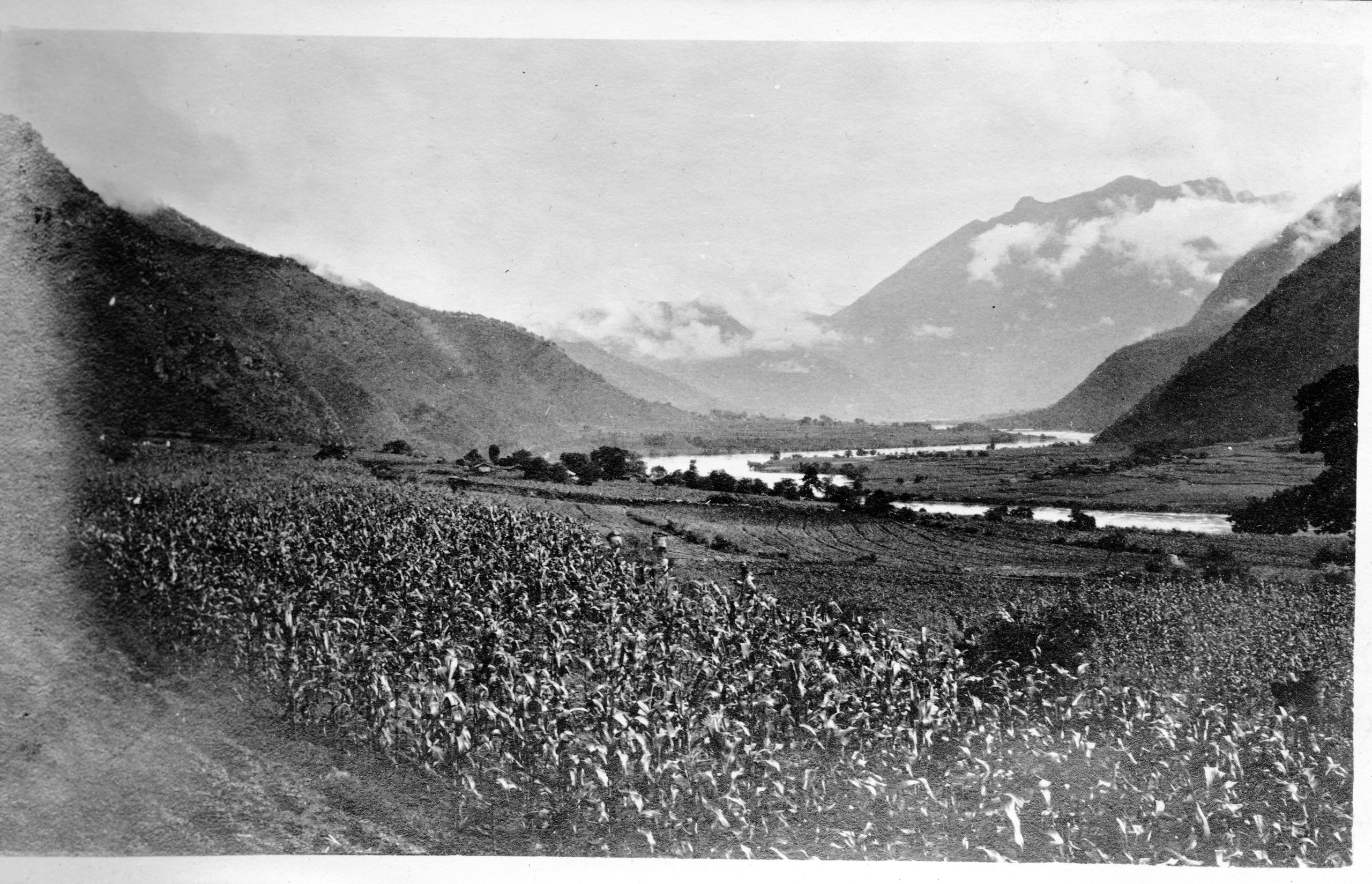

“The scenery today has been river scenery - the Great River always with us and great mountains on each side. Walnuts and chestnuts are grown in the low valley. Maize is the only crop, and no more rice now seen. The hills are sloping and well wooded. It is said there are many leopards in the woods. The rhododendron is locally called the Ch'a-shan-hua or Tea-hill flower”.

They arrived at Wu Luh Ting (6149 ft.) at 5.15.

Day thirty August 15th, 1923. Wu Lu Ting to La Pien Ku - 10¾ miles

They left Wu Luh Tien at 7.35 a.m. and followed the River bank of the Yangtze for 8 miles.

“Just before reaching the village of Chu Tien proper, we branched off to the left taking the Wei shi road. We walked for 2 miles along this pretty little river running down the Pa-tsi-chi Ho valley to join the Yangtze”.

“At 10¾ miles we reached La-p'ien-Ku (6149 ft.). Now the first signs of Tibet have appeared in the form of chortens and prayer flags. Outside the village we saw the first Chorten heap - or mané stones, with the inscription in Tibetan – om mane padme hum”.

In a letter home HGT said:

“Nothing special to note, except that (1) Pereira has just told me that we have travelled 444 miles to date, (2) I saw the first Tibetan prayer flags outside farm houses today - in fact this house in which we are has them - a long pole with a narrow flag like this”:-

HGT's sketch of a Tibetan prayer flag

HGT's sketch of a Tibetan prayer flag

Day Thirty-one August 16th, 1923. La Pien Ku to Lu-Tien - 16¼ miles

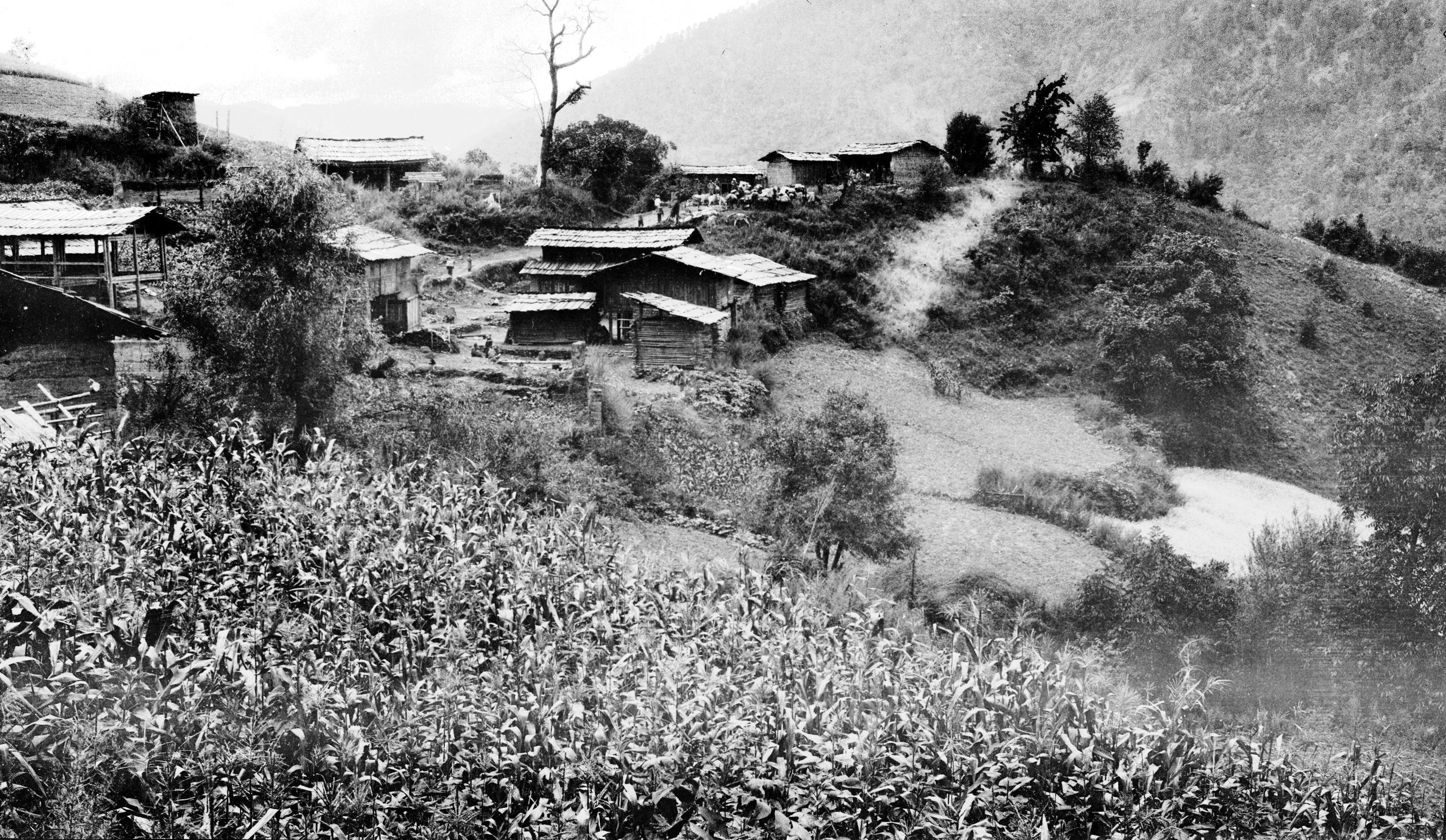

T’ai ping tang a typical hill top village near Sheh Ku crossing the Yangtze-Mekong divide

T’ai ping tang a typical hill top village near Sheh Ku crossing the Yangtze-Mekong divide

They started out in the morning at 7.25 a.m. Good weather until mid-day when they had more rain.

“We continued up the the pretty pine-wooded Pa-tsi-chi Ho valley, and at 6½ miles reached the top of the Hui-shao P'o, (7,477 ft.) From there we kept walking along the hill-side and at 9 miles reached the hill-top village of T'ai-p'ing-t'ang, (7,887 ft.) When the rain began we got on our ponies. After our mid-day halt for 2 hours, we arrived at Lu-Tien (8,107) a town of 310 families, at 4.45 p.m. The day’s journey was 16¼ miles in total”.

“We hope to reach Wei Shi tomorrow. It was too hot to develop last night, but I have got a film done this afternoon, which brings me up to date. Have seen about 10 patients since arriving here”.

Day thirty-two August 17th, 1923. Lu-Tien

“Rain during the night and this morning there is mist and rain so Pereira has decided to stay over today. I am rather sorry as I would have preferred the day in Wei shi. We are in quite a clean farmhouse - clean as things go, and so far, have managed to keep our bedding, and the things in our boxes dry. So if tomorrow is fine we will be glad we waited.”

“In the Lu-Tien valley rice as well as maize is grown. There are a good many walnut trees, some wild plums and a wild peach. Some rhododendrons are still in bloom at altitudes over 7,000 feet. Lutien, scattered among fields green with crops and clusters of trees and surrounded by high tree-covered hills, is very picturesque. Of the 310 families, roughly 60 are Chinese, 100 are Tibetan and 150 are Mosu. Three days' journey to the south are some Lisu. Maize is the chief food of the people, but they also grow wheat and barley for a first crop, and for a second crop buckwheat higher up, and rice lower down”.

“The religious character of the people is exemplified by our host. Three or four times a day he will go to the loft where there is a Buddhist shrine and will kotow before it, saying prayers and burning incense”.

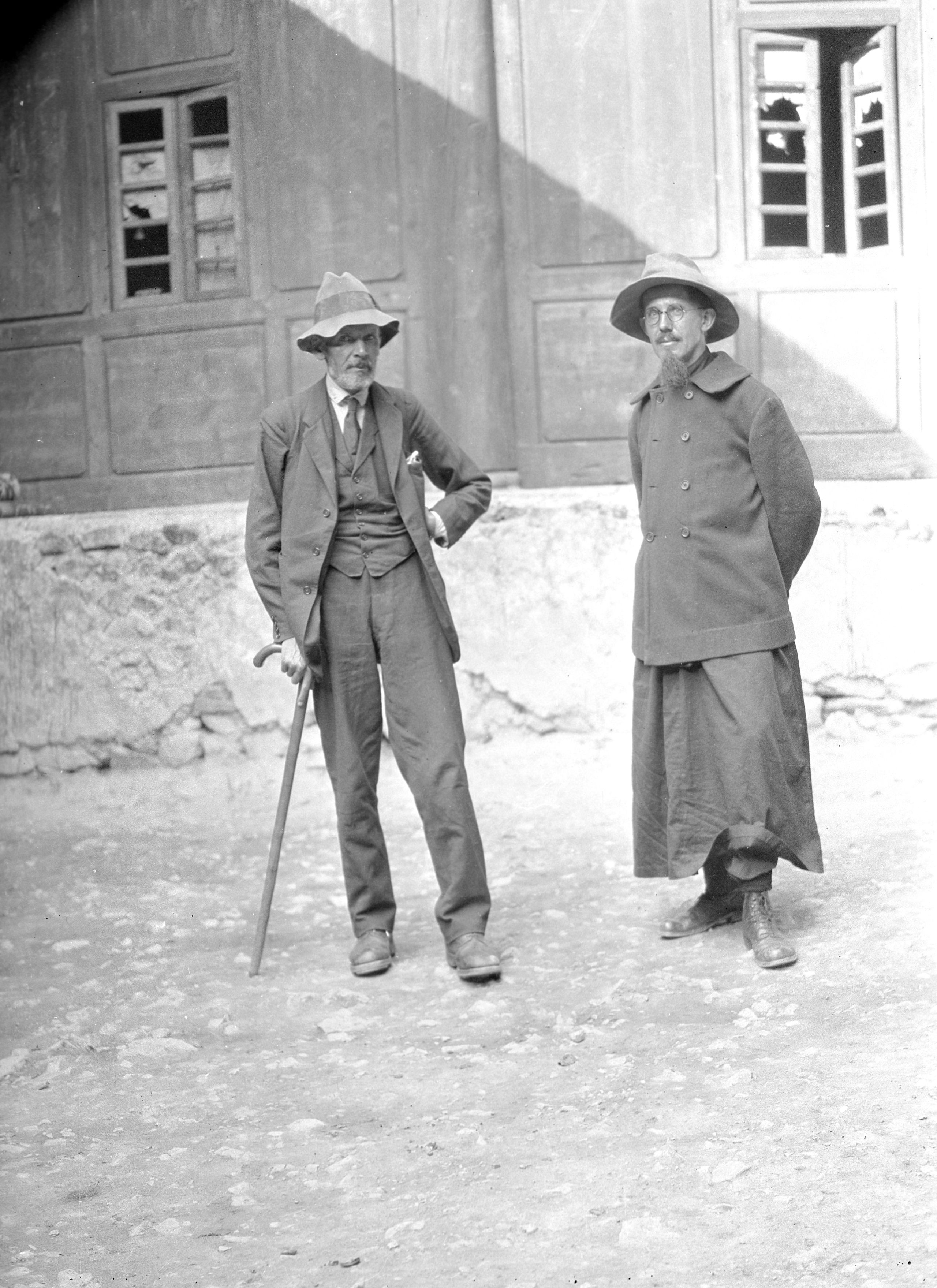

HGT noted in his letter that he admired GP and that the two of them were getting on very well together. GP kept busy working out the calculations of their route and altitudes on his map. He planned, on reaching Batang to send a message, (by wire from Taehienlu), to send a wire to Yunnan-fu and to Peking to say they had arrived.

Day thirty-three August 18th, 1923. Lu-Tien to Wei Shi - 18 miles

They packed up and started from Lu-Tien in fairly fine weather, but soon mist and rain arrived. They climbed for 2,600 feet through woods by easy zigzags to Ta-shih-t'ou P'o, (10,755 ft.), also called Si-jam-bu in Mosu, which they reached at 5 miles. They were in a kind of hollow in the hills, and it was the divide between the watershed of the Yangtze and that of the Mekong. It was 4,760 feet above the Yangtze, which they had left at Chu-tien.

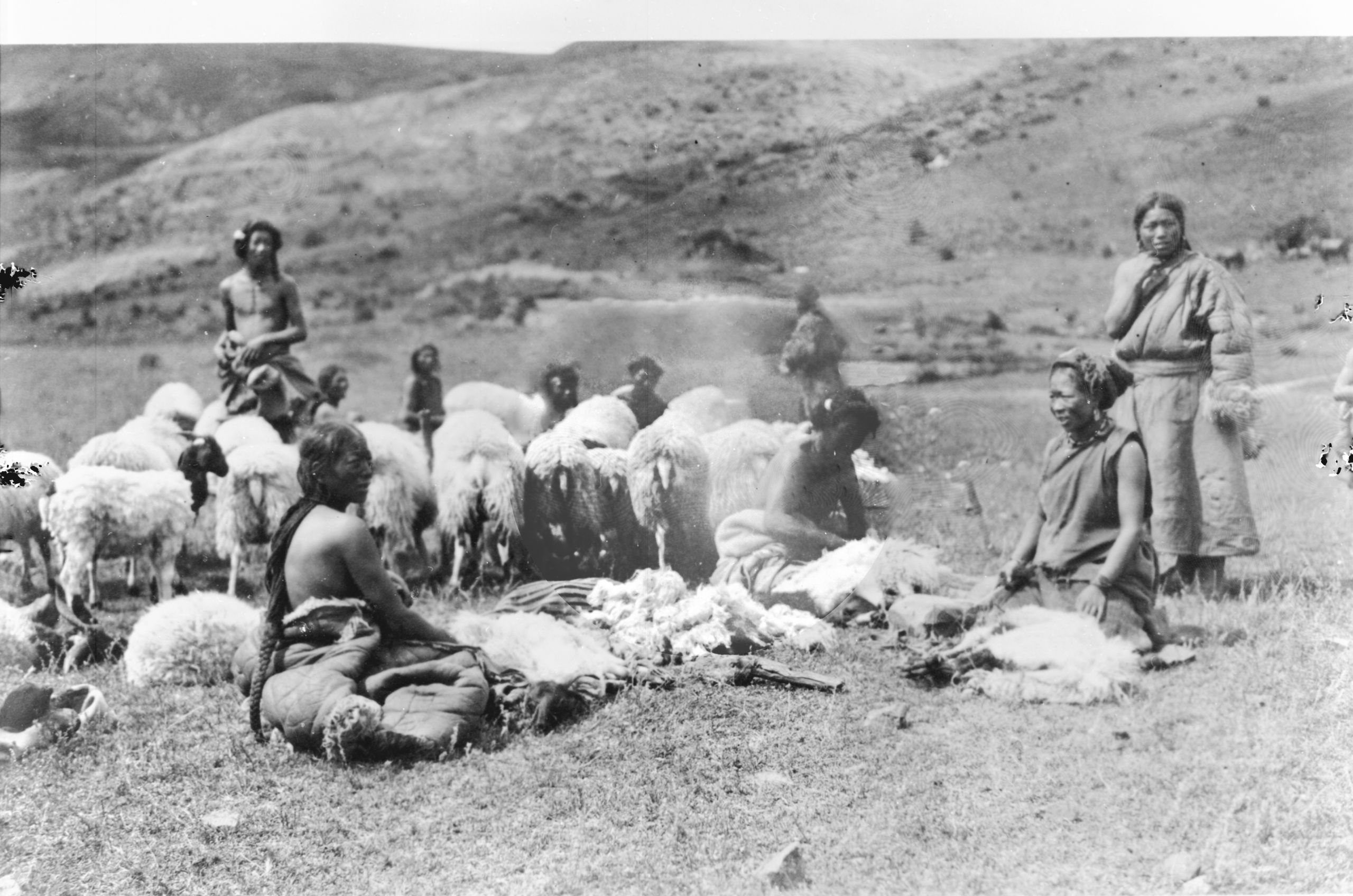

“Having reached the valley, we travelled along 3 miles of the most beautiful level country with lots of flowers. The most numerous one was a yellow prunula and there was also a beautiful little purple flower like an anemone. We also saw a huge flock of sheep and goats, probably about 250, grazing on the wide level space - which had a most delightful carpet of grass and was surrounded by thick woods of pine, and maple, and fir”.

“After the 3 miles of undulating grassy plateau, we came to an old Lisu hut at Li-ti P’ing. It was beginning to rain as we stopped for our mid-day halt. We had lunch in the shelter of the old disused hut. During lunch it began to rain heavily, so we hurried up and started again at 1.15 p.m”.

“It poured with rain during the afternoon and we got soaked”.

“At 16½ miles after a slight rise, it was all downhill - a drop of 3,700 feet. The descent in spite of the rain, was beautiful - through great pines 50 to 60 feet high - the road running for the most part along the top of a great spur of hill. Occasionally the mist lifted and we got a brief glimpse of a great range of mountains opposite, which evidently helps to form the Mekong valley. As we went down we crossed 2 streams, swollen with the rain.

“I was so wet that I paddled through one, the little bridge was gone - the water only came up to my ankles but as my boots were already soaked inside and out I did not mind. I had walked up to the top and now got into my Burberry and waterproof cape and walked down. It was a hard tramp, as it poured with rain. I kept dry above, but from 6 inches above the knees and downwards I was just soaked. As I was nearing the bottom, one of the Tibetan muleteers overtook me and one of the escorts. I sent them on to find a place for the night in Wei she and followed on down”.

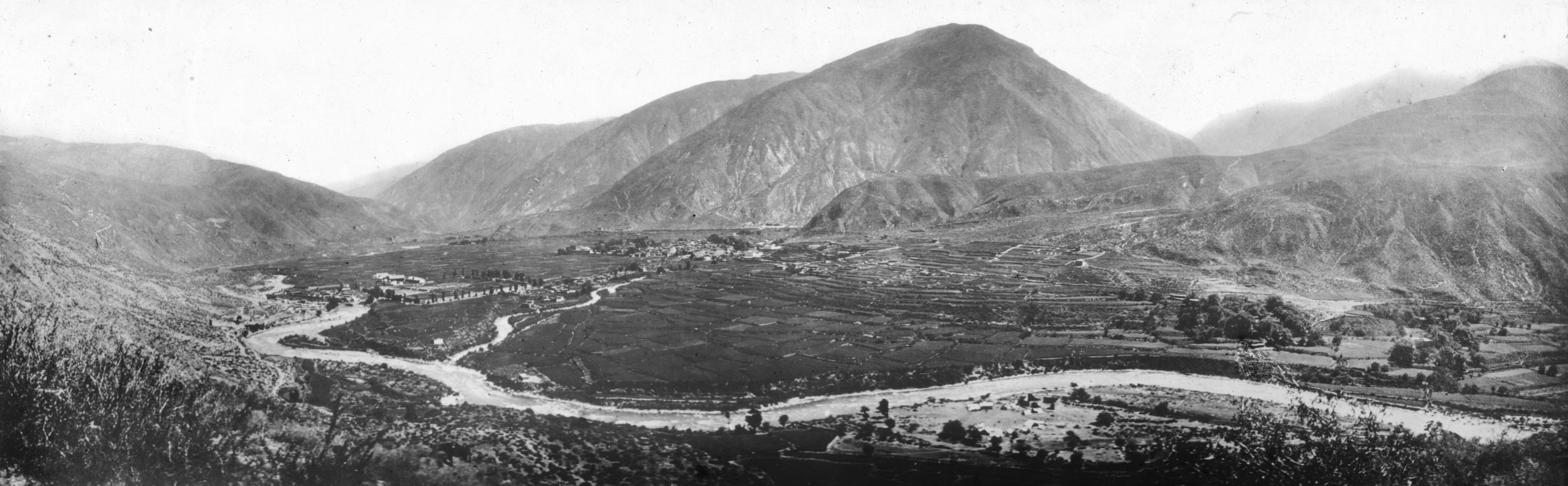

Looking South along the Mekong Wei-Shi in distance

Looking South along the Mekong Wei-Shi in distance

“At last Wei shi came into sight. A nice river running North, made the approach very pretty. The Wei-shi Ho was crossed by a high, open, and very well made wooden bridge and after the day’s journey of 18 miles, we arrived at 5 p.m. at Wei shi-hsien (7,016 ft.), a city of 250 families. In the city the population was Chinese, in the valley Mosu, and in the hills Lisu.

“I was met by the muleteer who took me to a house where we are to stay. At first the people did not want to give shelter and offered to show them an inn, but when I told them how wet and tired I was, they became very friendly. They brought some tea, a charcoal fire in a brazier, and felt mats to sit on”.

After about 20 minutes GP and the rest of the caravan arrived.

“Before changing I went to the Post Office to see if by any chance there were any letters. I then went to the Gospel Hall, run by a Mr Lewer. Mr. Lewer showed me around his new house and told me to help myself to vegetables. I got two cabbages, two cucumbers, a few beans and the caretaker promised to bring down a little fresh milk. I was glad to get back to the place where we were staying and get a change into dry things. I stretched out two lines and set the things to dry”.

Day thirty-four Sunday August 19th 1923. Wei Shi

“It is Sunday, and pouring with rain today, so we decided to wait over a day, especially as Pereira was a bit off colour. I dosed him up and advised him to keep quiet, so he stayed cosy in bed for breakfast. It was very raw and cold. GP wrapped himself in his great coat and I got out my fur waistcoat and was quite glad of it. After breakfast, I walked up to the P.M.U. Gospel Hall, but as Mr. Lewer was away there was no service".

“The Hall is being looked after by Mr. Hwong, the evangelist, and Mr. Tuh the caretaker, who were very pleasant. I went with Mr. Hwong to his home and saw 3 patients there. One was the builder of the new house, who since the 3rd month has developed glands in the neck, which appear to be malignant. Local people had said it was because he is building for the missionaries – I fear it would prove fatal within 12 months. He saw some more patients during the day - altogether 12.

“On returning to our lodging, I found GP feeling better and up and about. It poured with rain all day, but began to clear at dusk and by bedtime the mountains were visible, and things looked better”.

Day thirty-five August 20th, 1923. Wei Shi to Ka Ka Tang - 14½ miles

Weather fine - sunshine. They left Wei shi at 7.15 and then stopped a little over half way at La Puh-an-Tong. At 4 ¼ miles they crossed the Wei-si Ho by a bridge to the right bank and continued down the valley, passing over the lower spurs.

GP noted: “Ninety soldiers, mostly boys, were also going to A-tun-tze, and passed us twice on the road. Some of the soldiers, besides the officers, were riding. The transport consisted of a few mules, and often the muleteers were carrying seven rifles apiece”.

Falls between Wei Hsi and Ka Ka Tang on the Wei Hsi river

Falls between Wei Hsi and Ka Ka Tang on the Wei Hsi river

“After 8 miles the hills were more sloping and the trees more in clusters. The scenery was beautiful. We had 1¼ hours rest at lunchtime and then travelled on to Ka Ka' Tang (6312 ft.), arriving at 4 p.m. Total distance 14½ miles. Walked all the way. Steady downhill, quite easy going. It was quite hot again, in the sun”.

Ka Ka Tang had 13 families. The people in the village were practically all Chinese, with a few Tibetans. The Mosu and Tibetans (who round there were called Lamas) mostly lived on the hill-sides; and the Lisu lived behind in the higher ranges. GP noted: “the milder Lisu had been pushed back at first by the more virile Mosu, who had assimilated more with the Chinese”; and then “the Mosu in their turn had had to give way to the Chinese”.

“We found a good clean house to stay in at the extreme North end of the village. It has a crescent opening cut in its wooden wall and is quite clean and new. It seemed that there would be 3 sleeping in our room that night, as there was a coffin at one side, fortunately it was well sealed. Later we found the coffin was not inhabited; it was the property of the old main proprietor. He said it was ready for his decease”!

Day thirty-six August 21st, 1923 Ka Ka Tang to Hsiao Wei Shi (Little Weishi) - 19¼ miles

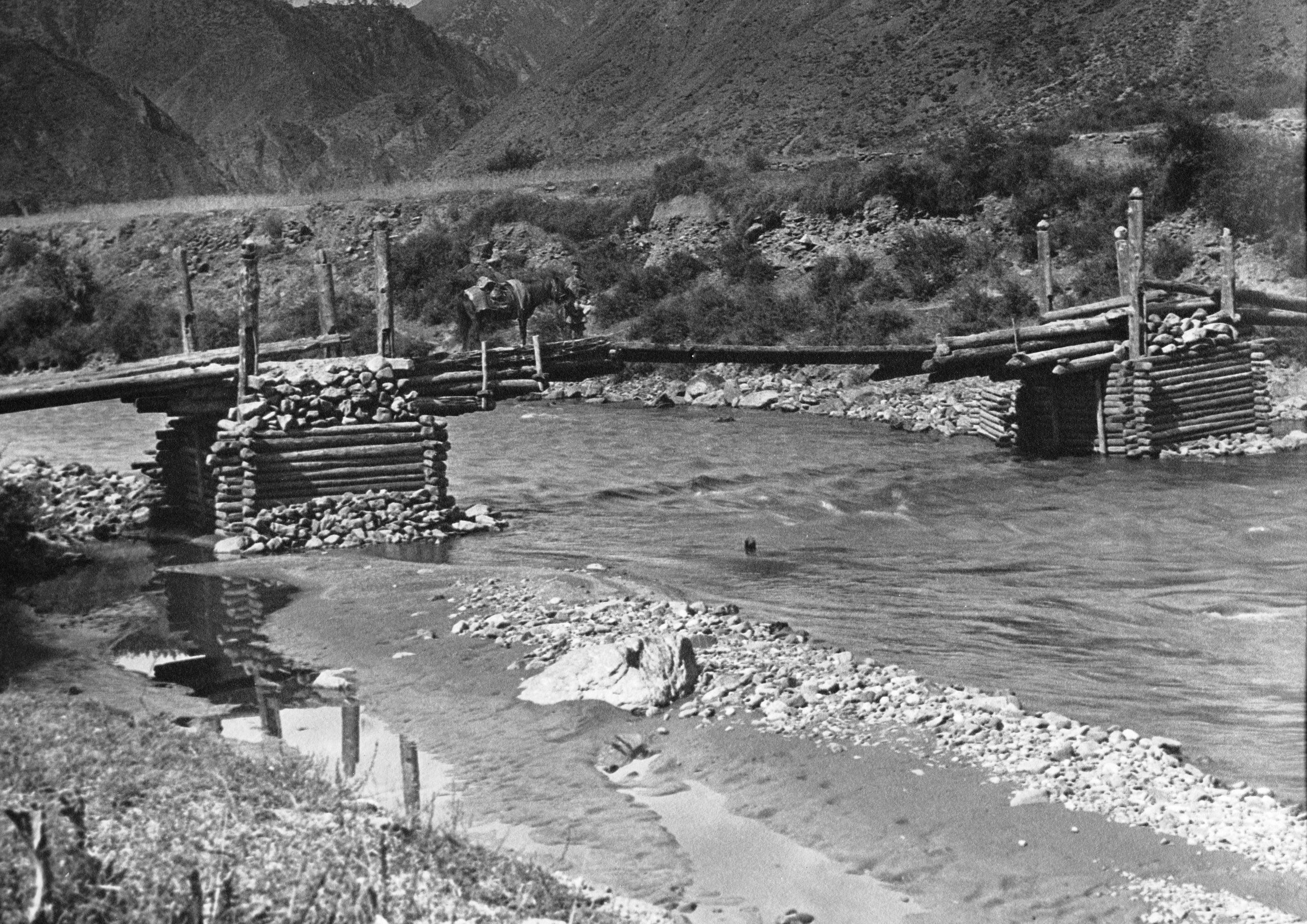

“A wonderful day's journey. We left Ka Ka' Tang at 7.20 a.m. and followed the Wei Shi River. There were numerous places where the path had almost slipped away, and the muleteers had to get one on each side and give the mules a push as they passed over, lest they should toboggan down with the loads”.

Near the landslides between Ka-Ka-tang and A-nan-doh-t'ang

Near the landslides between Ka-Ka-tang and A-nan-doh-t'ang

“The Chinese now appear not to describe distance in li - all is reckoned in Tong - which is very variable.The journey is divided into three Tong - each Tong said to be 30 li - but really it only means a section. The first tong being 5¾ miles from Ka Ka' Tang to the little hamlet of A-nan-do-t'ang”.

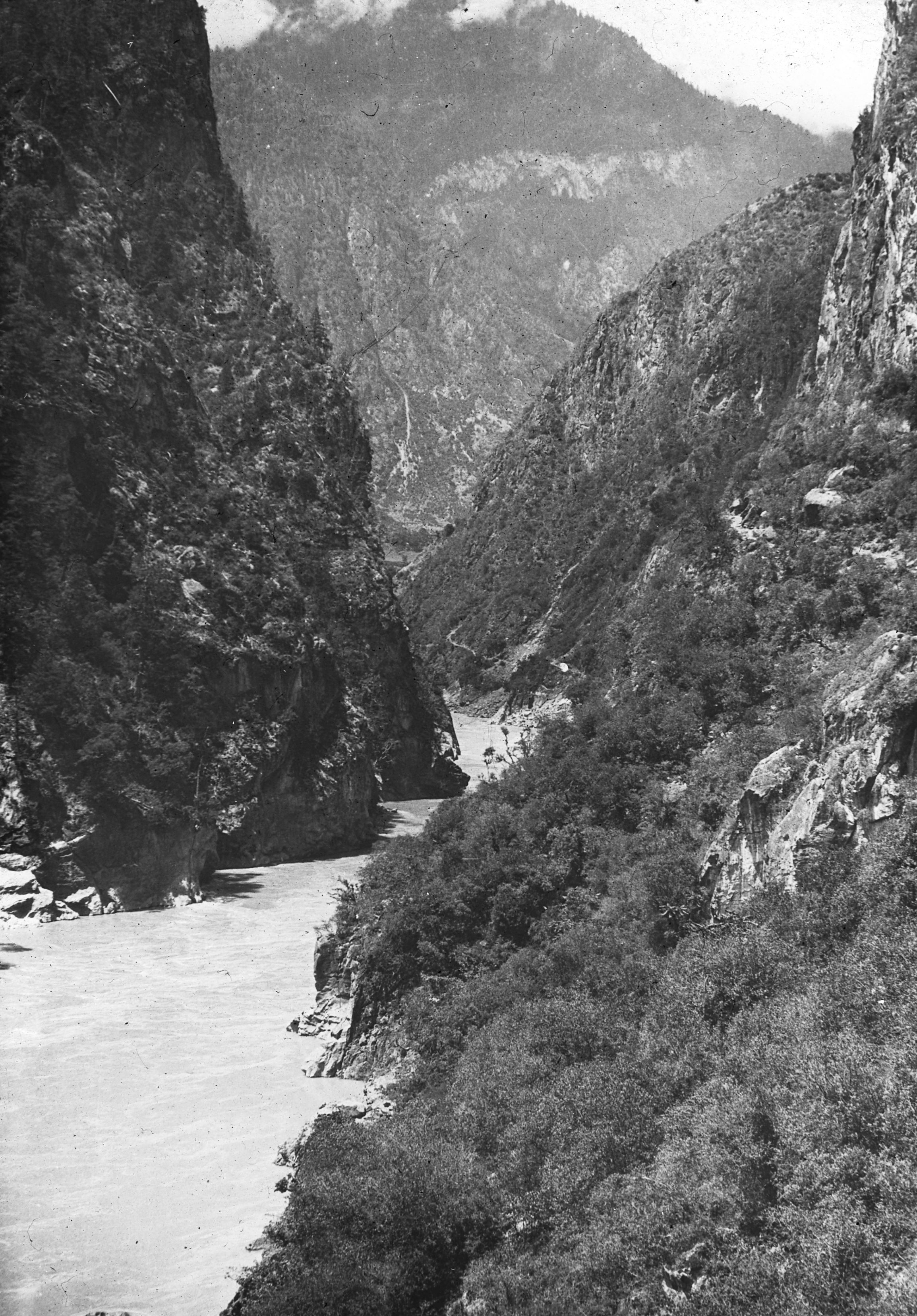

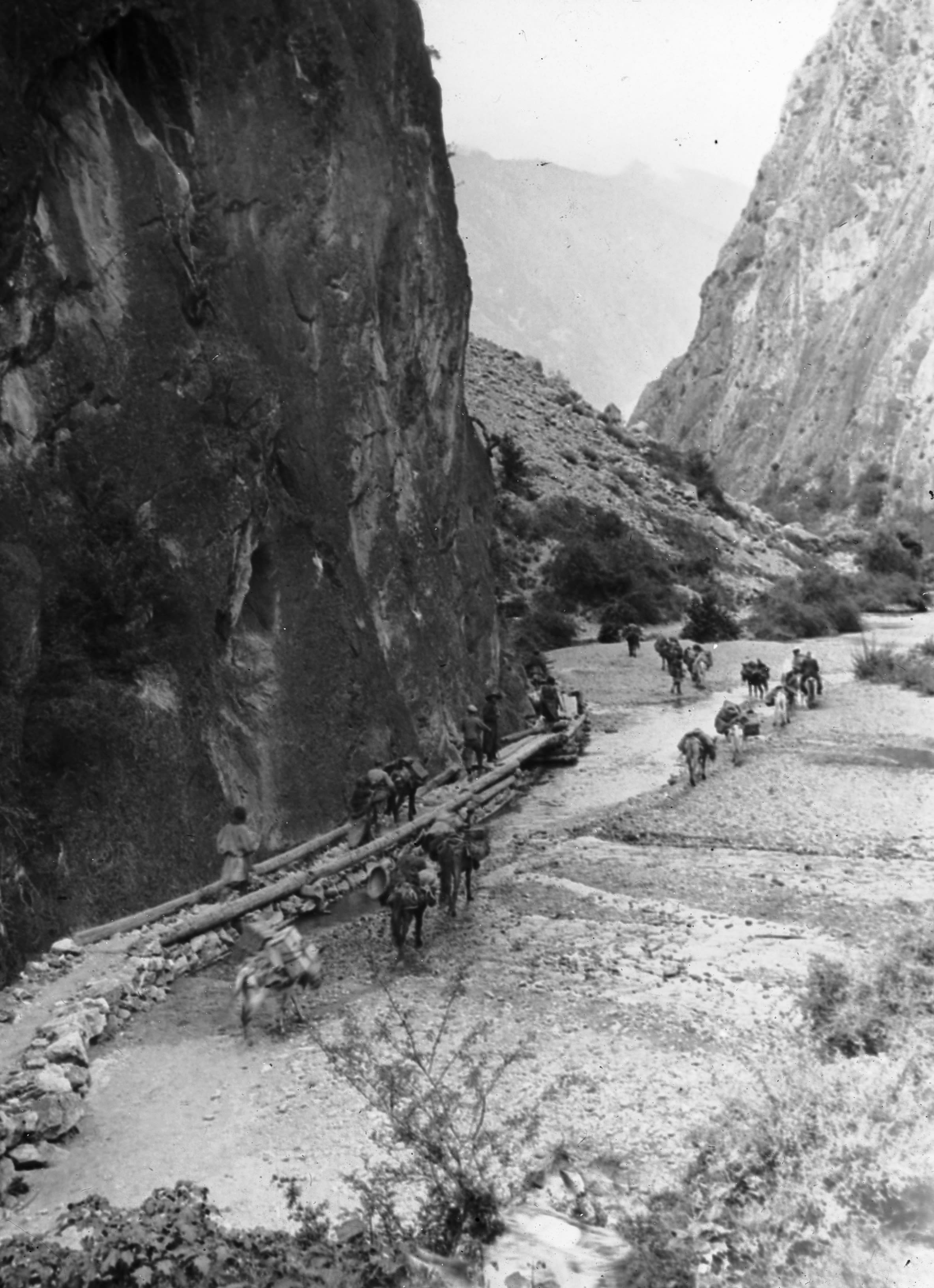

“The second part of the journey to Peh Chi Shun (6 miles) was the most interesting, for the Wei shi River suddenly gave a big bend to the West and as it were, broke its way between two big mountains, great cliffs on each side, and the foaming torrent below. The road was cut out of the rock in places – like the gallery at the Si Shan (or Xi Shan) temple in Yunnan – with the cliff going vertically down to the water's edge - about 200 ft. below”.

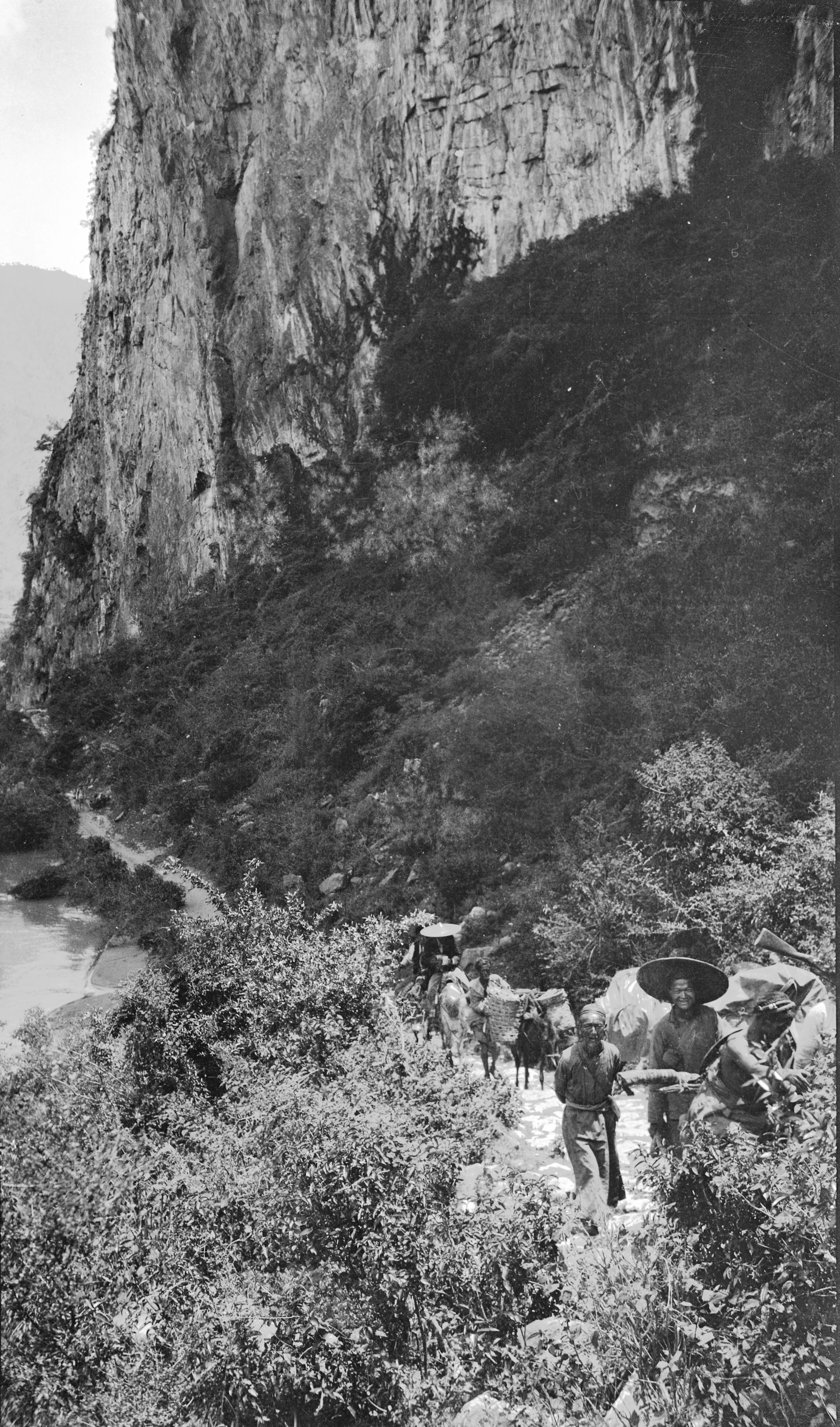

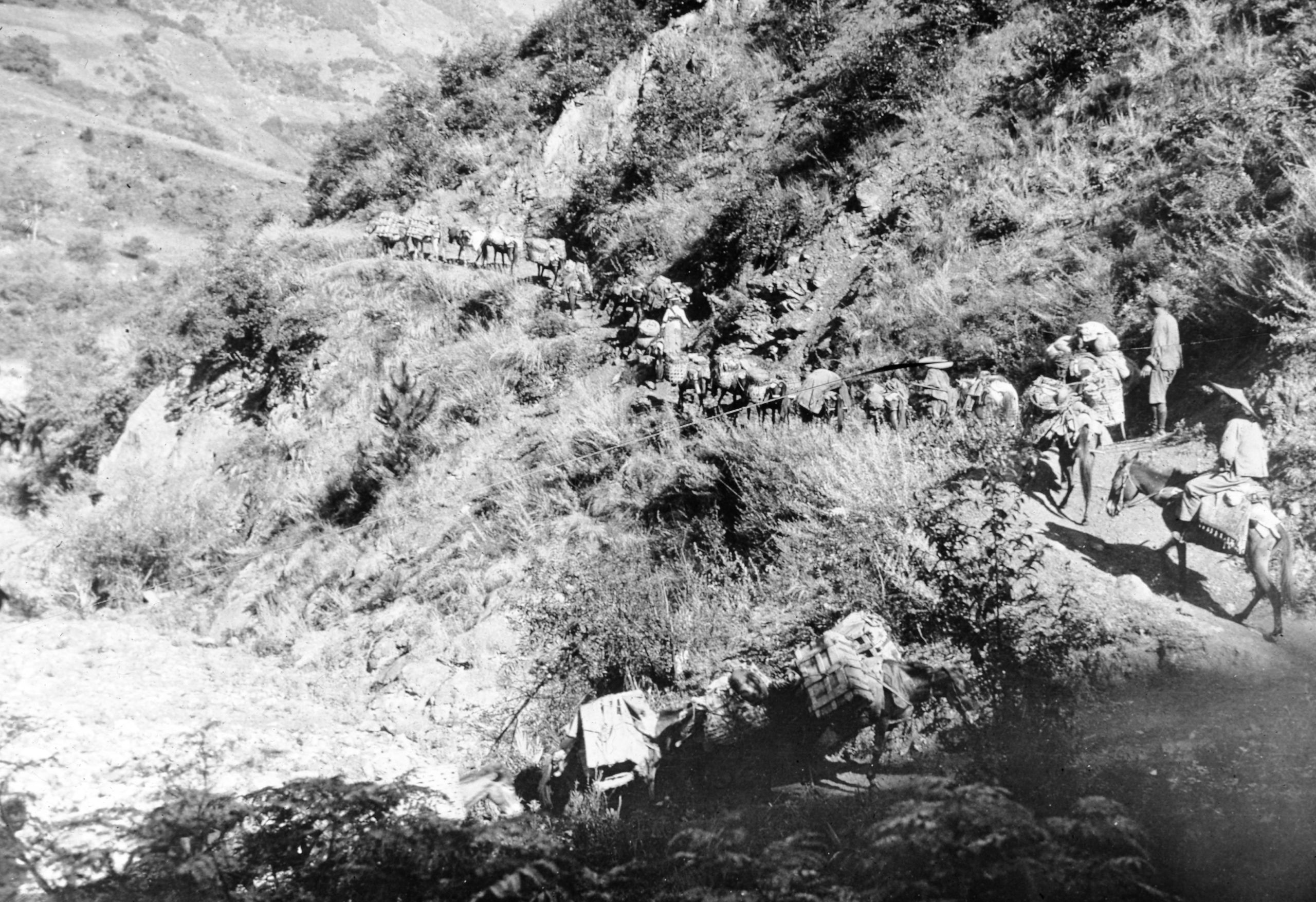

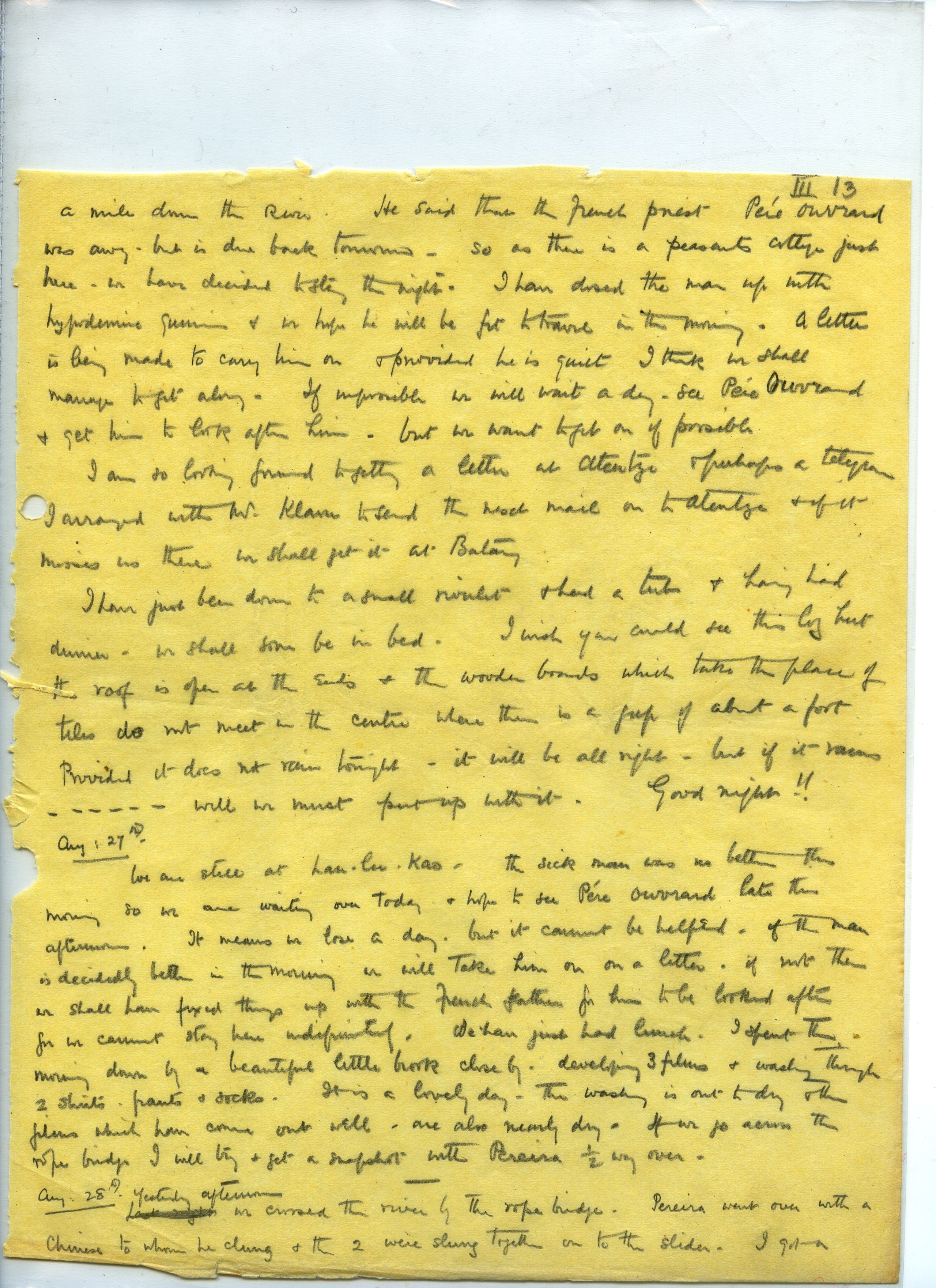

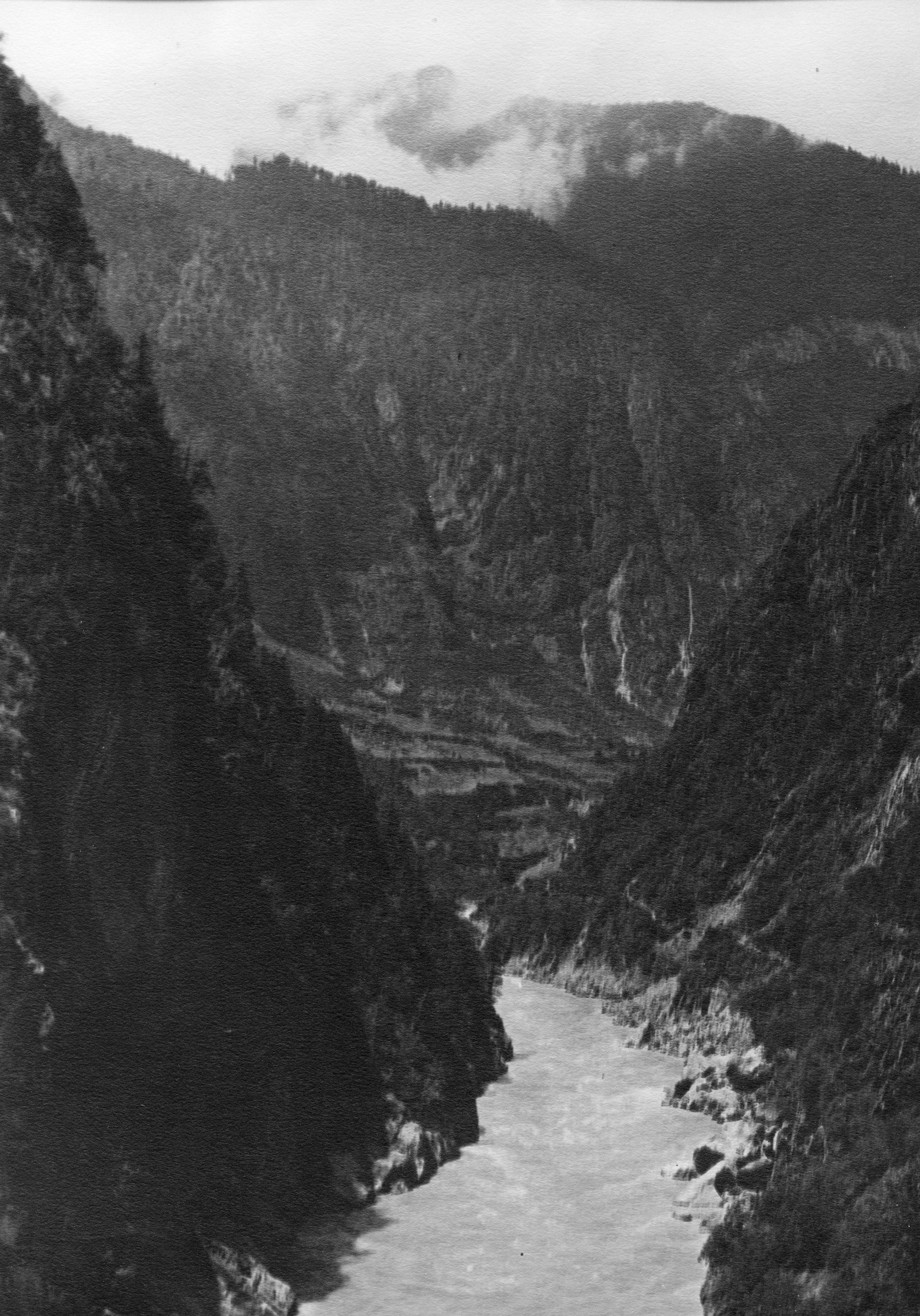

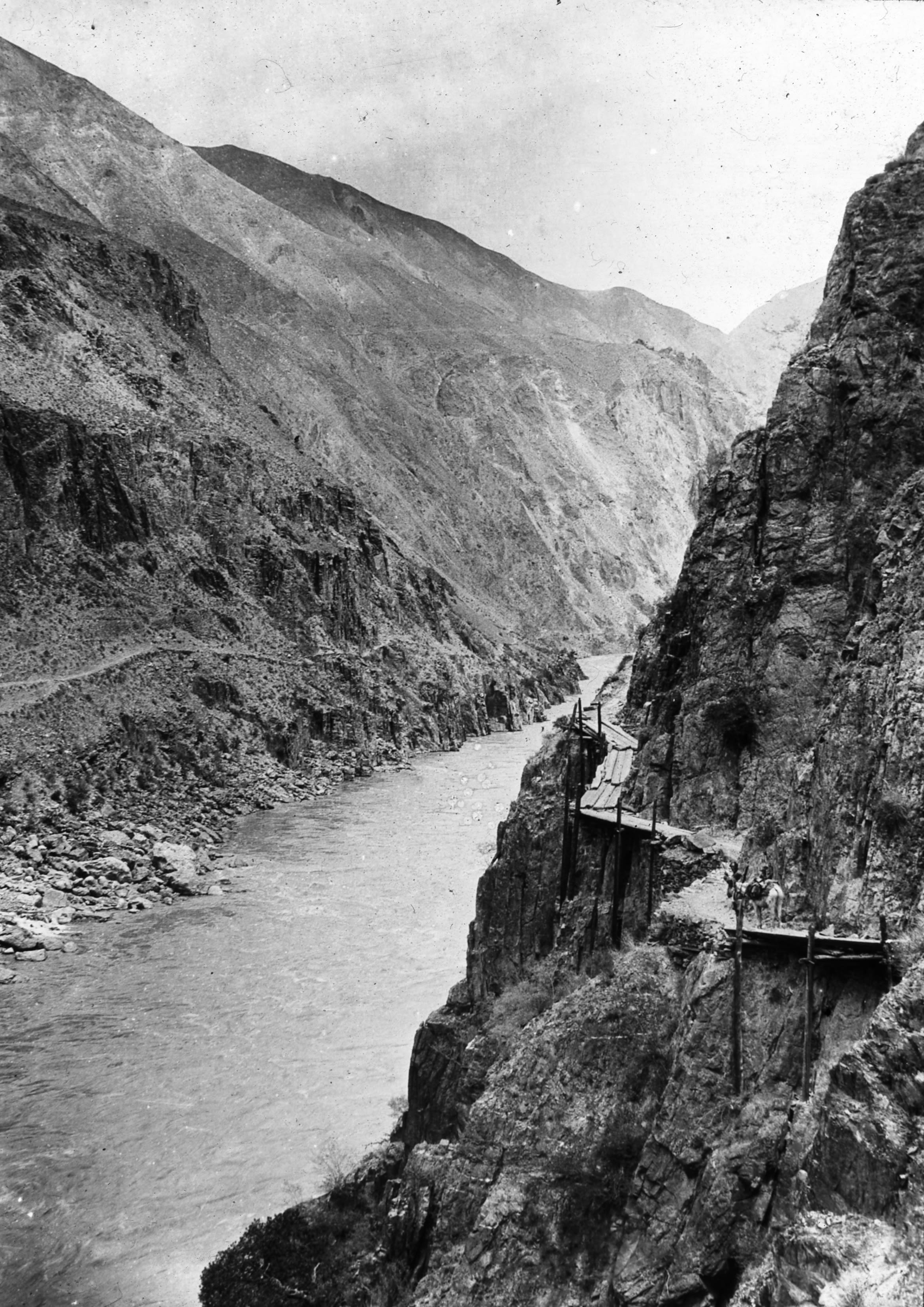

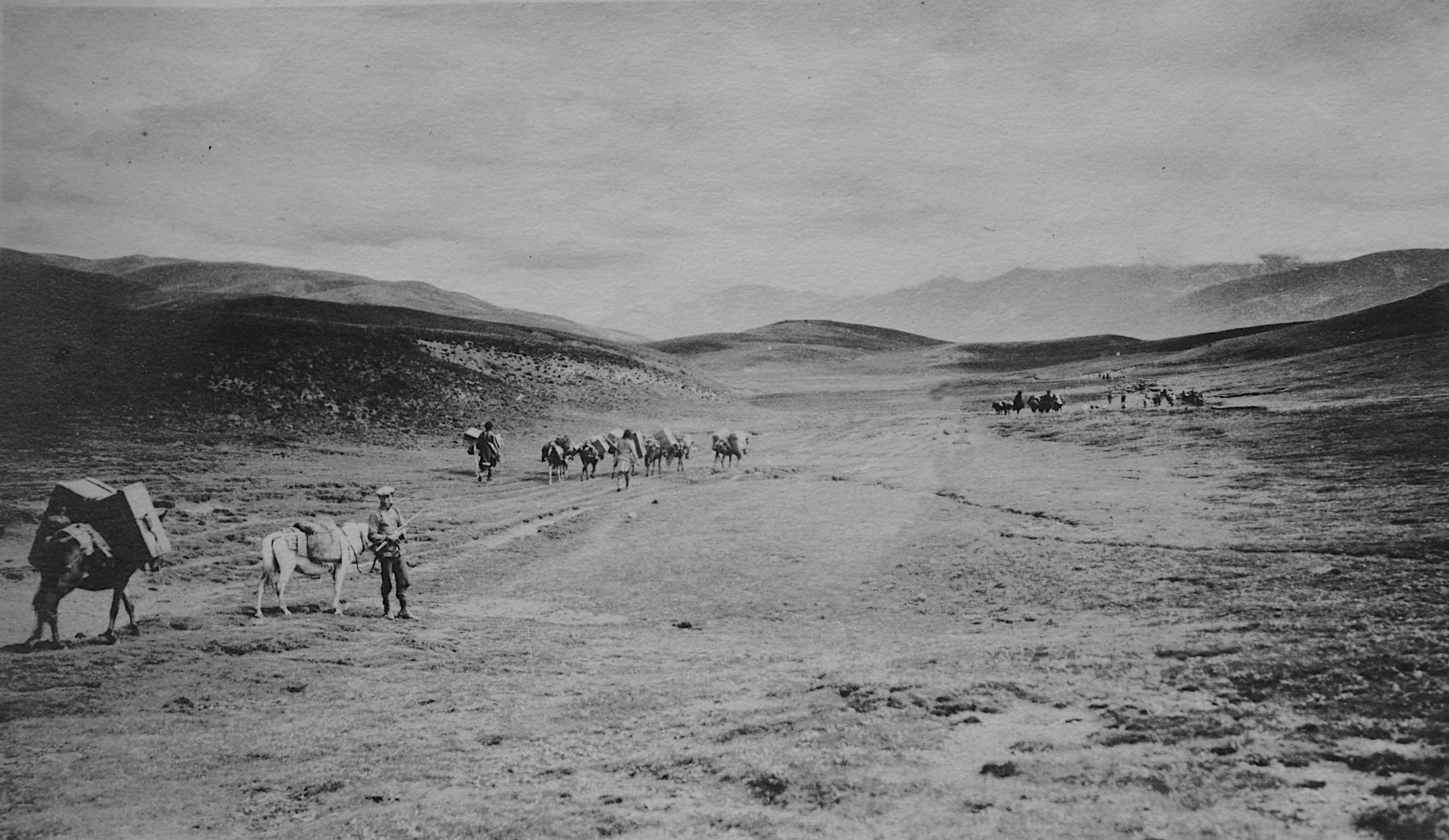

The breakthrough of the Wei-shi river to the Mekong approaching Hoh-chiang-ch'ao. Transport on the road

The breakthrough of the Wei-shi river to the Mekong approaching Hoh-chiang-ch'ao. Transport on the road

“In one place the path was cracked and it seemed as if the next rain must certainly bring it down - the muleteers carefully piloted the mules over. I should have been rather anxious for the loaded mules if the weather had been bad - fortunately it was a glorious sunny day, and the road being stony and sandy, had quickly dried”.

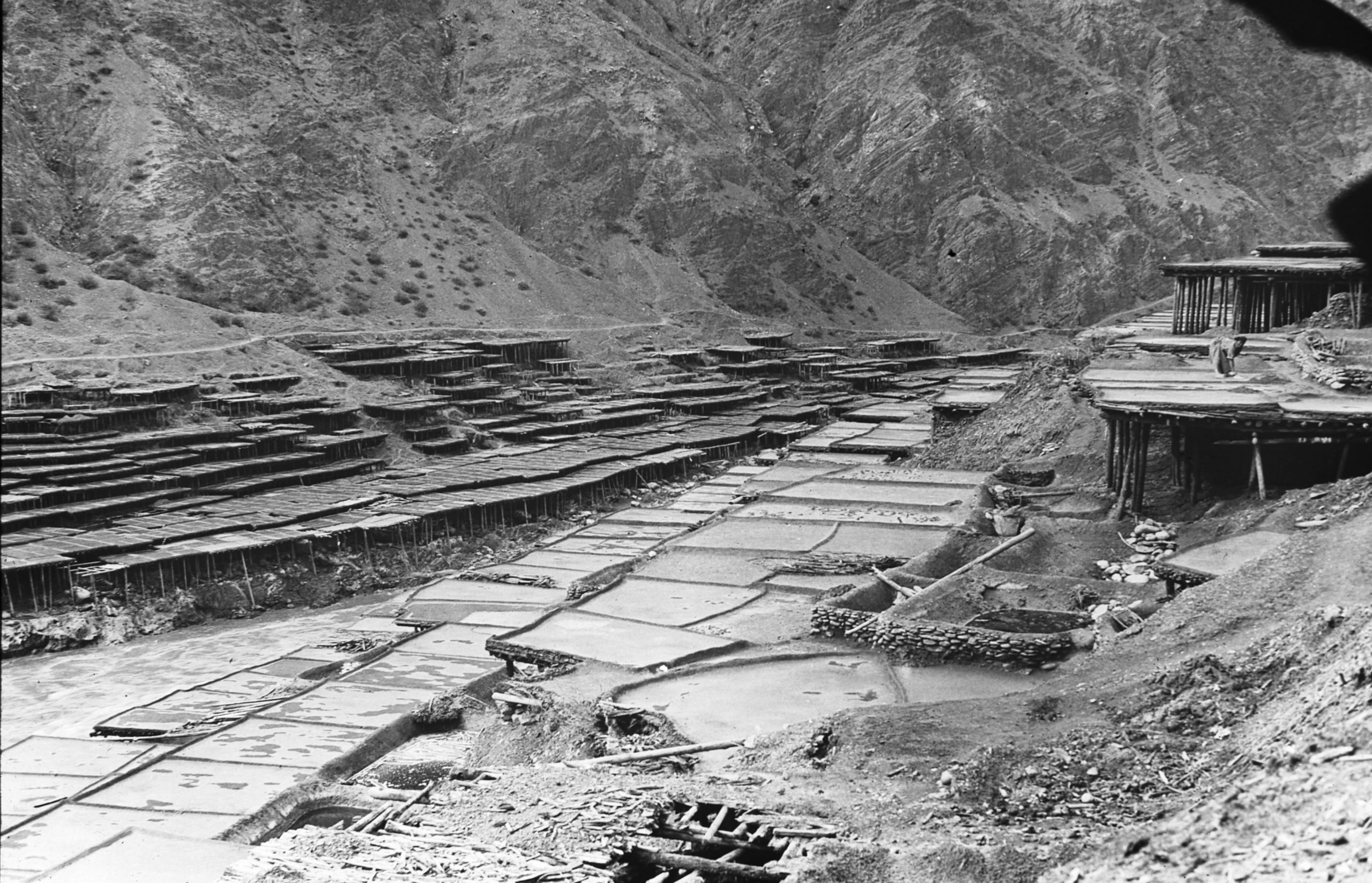

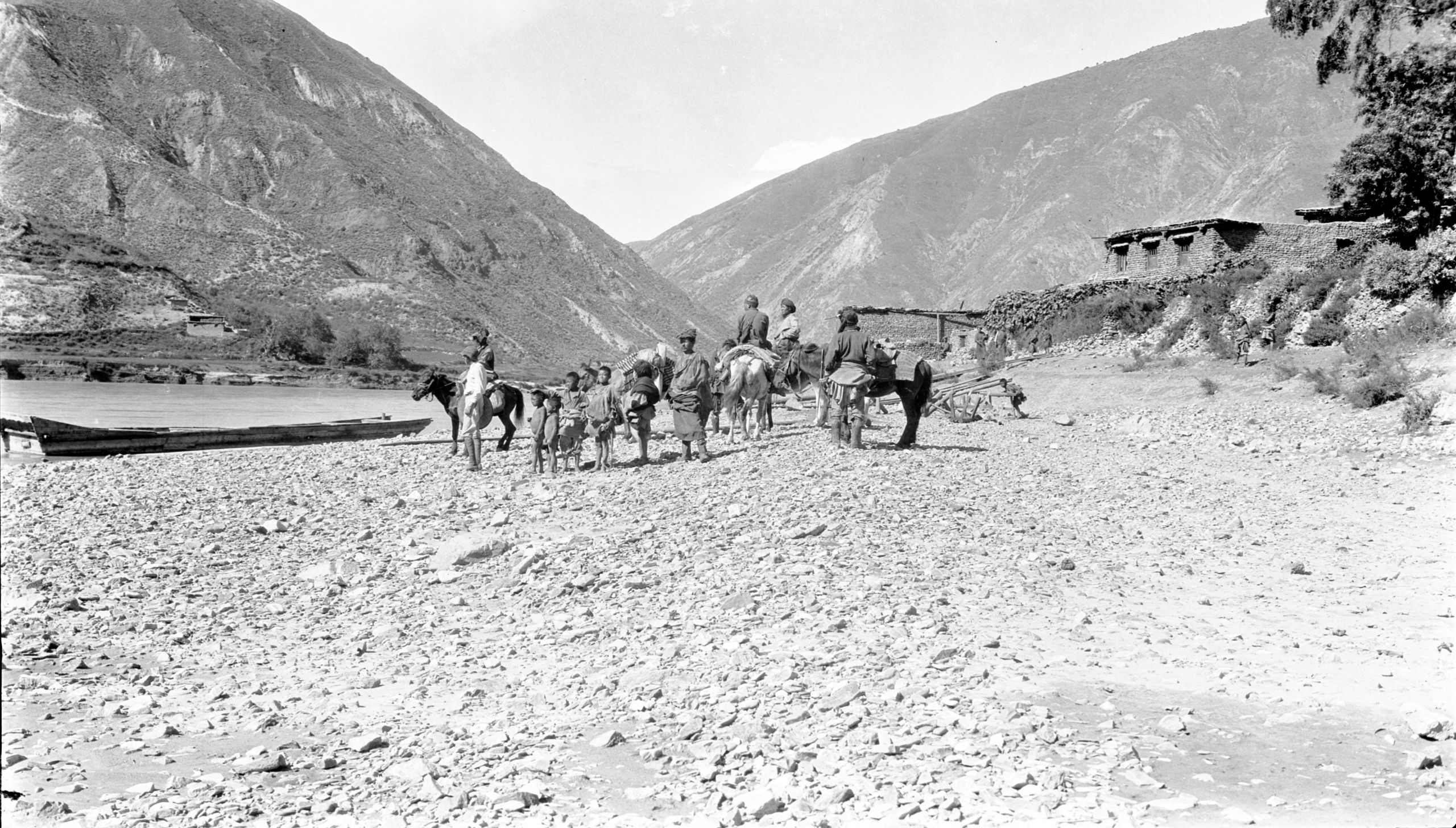

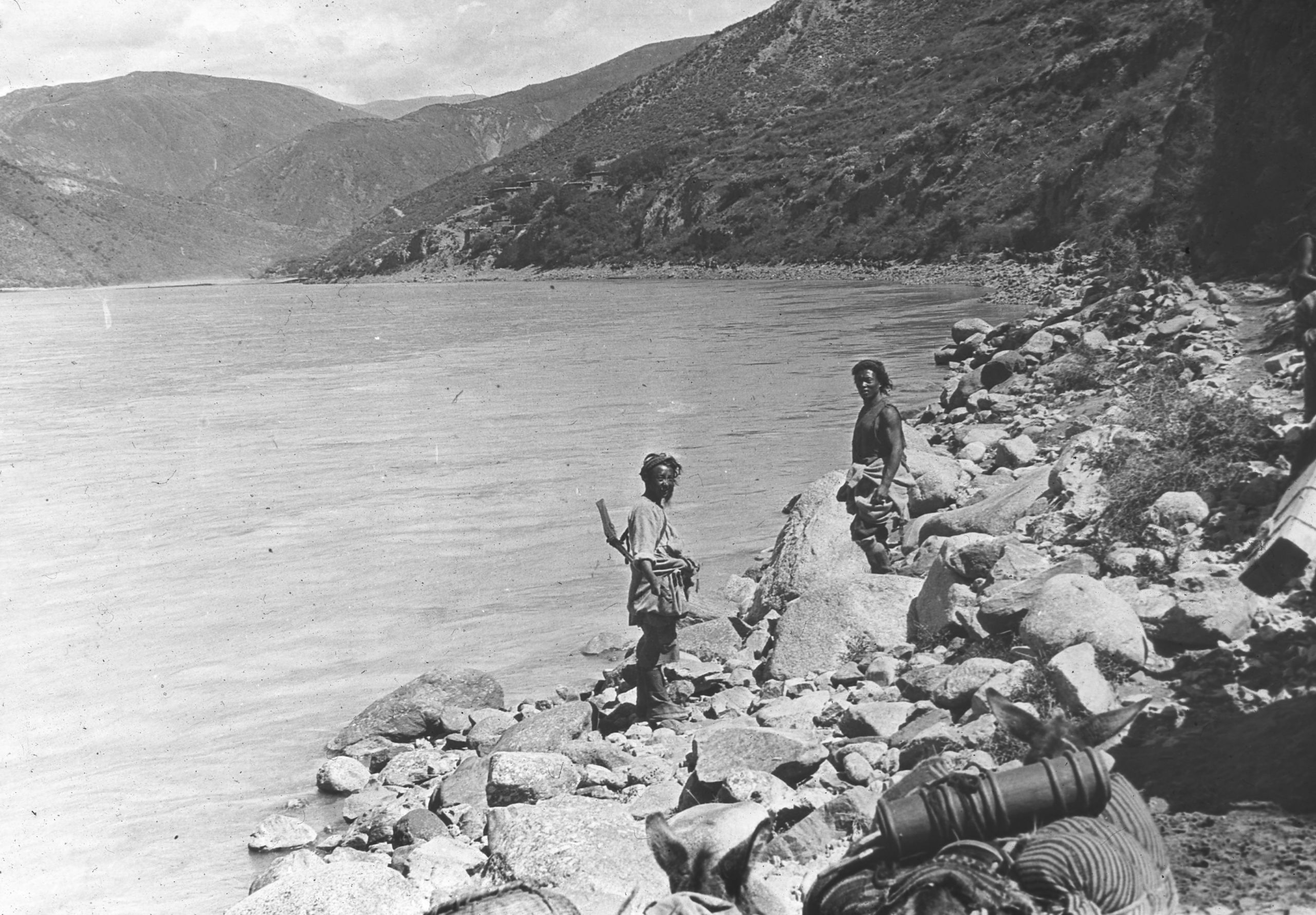

“The road then lead down the narrow and beautiful Alando gorge between high, precipitous, rocky, wooded hills. After a mile or two through this gorge - suddenly the Mekong came in sight - a wide rapid but placid river, such a contrast after the roar and noise of the small Weisi River in the gorge. The river at this point (altitude 5,896 ft.) was called the Lan-tsang Chiang or Dza Chu.The road then turned North and we were at Hoh Chiang Ch'ao where we saw our first rope bridge - a most extraordinary way of getting across the River".

Rope bridge on Hoh-Chiang-ch'ao (Mekong)

Rope bridge on Hoh-Chiang-ch'ao (Mekong)

“A big rope made of twisted bamboo is stretched between two posts on opposite sides of the river. There is naturally a sag in the rope - each man who wishes to cross has his own apparatus, consisting of a short piece of thick bamboo, with one side cut away - forming a slide on which the sling is fixed. The sling consists of a piece of cloth or rope on which the passenger sits, another piece of rope slings the head, and a third the knees. When ready the man pushes himself off and slides rapidly down to the middle of the sag, about half way across the river - then he hauls himself up hand over hand to the other side. In some places there are two ropes a little distance apart, with the end on one bank higher than the other, so that one can slide practically all the way across. The second rope has the highest end on the opposite bank, and is used for the return journey. The rope bridge at Hoh Chiang Chao was about 150 yards long”.

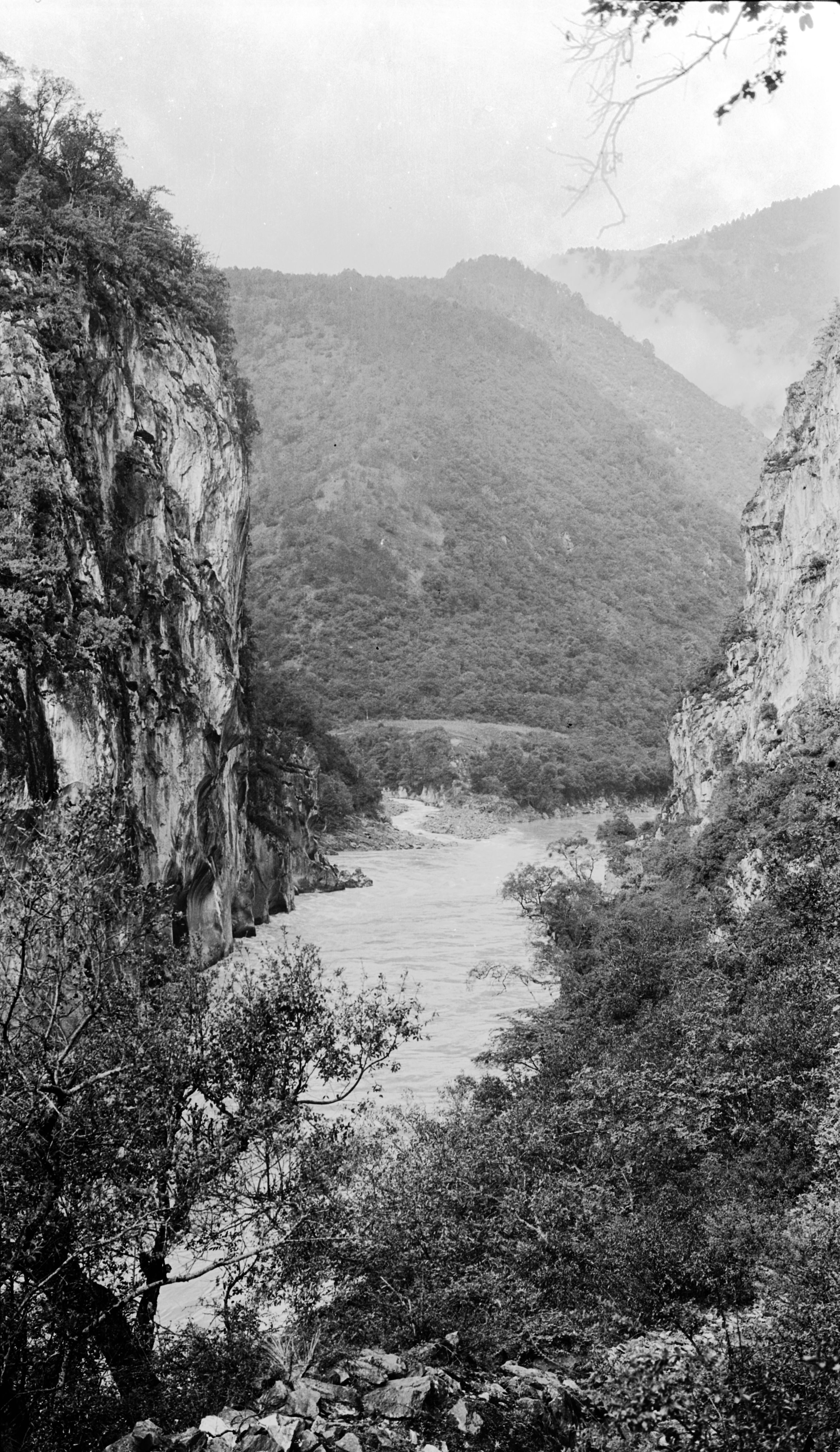

The breakthrough of the Mekong between Peh-chih and Kuan-fun-Ping (5½ miles from Pau-teh)

The breakthrough of the Mekong between Peh-chih and Kuan-fun-Ping (5½ miles from Pau-teh)

After lunch at Hoh Chiang Chao (altitude 5,394 ft.), they set off again at 1.20 p.m. and in about ¼ of an hour were passing through Peh Chi Shun (5½ miles from Pau-teh), a good sized village with a paved street and houses on each side. The road then lay along the left bank of the Mekong River and at 5 p.m. they arrived at Hsia Wei Shi (Little We Si). They were then told that this was not the end of the third Tong, but that was at a place called Ai Wa.

“The road by the side of the Mekong is very pretty; numerous walnut trees helping to shade the path. On the West bank the mountains rise abruptly to several thousand feet, and on the left, or East bank, they seem to do the same, but we can not see it so well as we are travelling under the lee of these mountains”.

“Having arrived at Hsia Wei Shi (5610 ft.) we are now staying at the R.C. Mission. The Chinese priest, a very pleasant man has put a room at our disposal and we are very comfortable. He says there are only about 30 families, four-fifths Chinese and one-fifth Mosu. Li Su live all round on the hills. The R.C. mission has a small school with about 7 children.

Day thirty-seven August 22nd, 1923. Hsiao Wei Shi to K'ang Pu - 17 miles

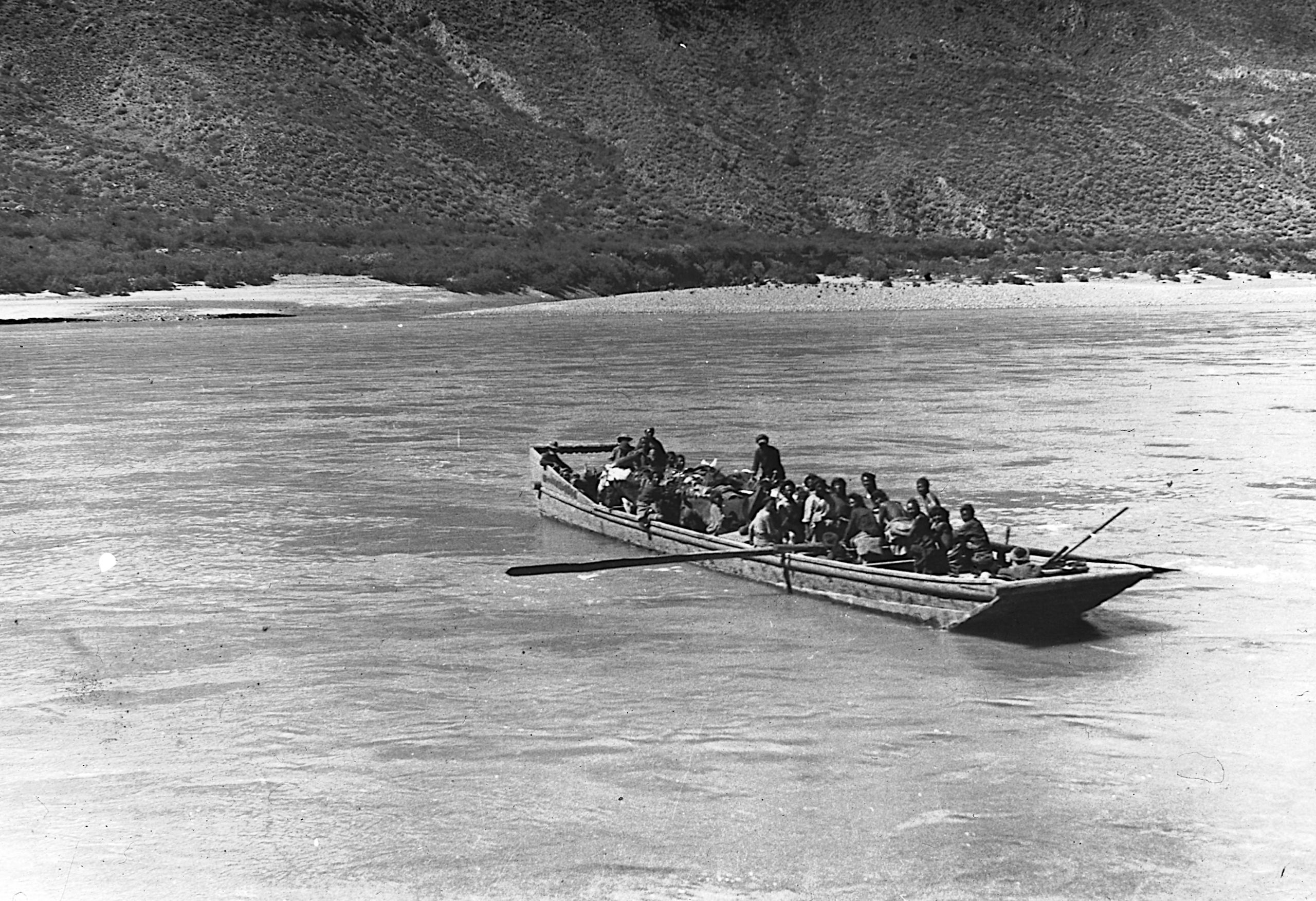

Another day - following up the left bank of the Mekong – They left Hsiao Wei Si at 7.40 a.m. The going was easy all day, without any steep climbs. The hills were mostly sloping and well- wooded. The crops were maize and millet and, when the valley was more level, rice. At Ai-wa (5,448 ft.), after 7½ miles where they rested, there was a ferry boat, but the road to A-tun-tzu continued up the left bank of the river, and three or four tributaries had to be crossed by rope bridges.

“In the hills we are told there are leopards, bear, roe, wild boar, and serow (a type of goat or antelope), but no pandas or tigers”.

“The Mekong seems somewhat different to the Yangtze in that the banks slope very steeply up, whereas the Yangtze banks are either vertical or slope gradually, with lots of cultivated land. The amount of land which can be cultivated on the Mekong appears to be small, though one can see away up on the mountain sides several thousands of feet above the river - occasional Lisu cottages with a patch of cultivated land, growing mostly millet and maize”.

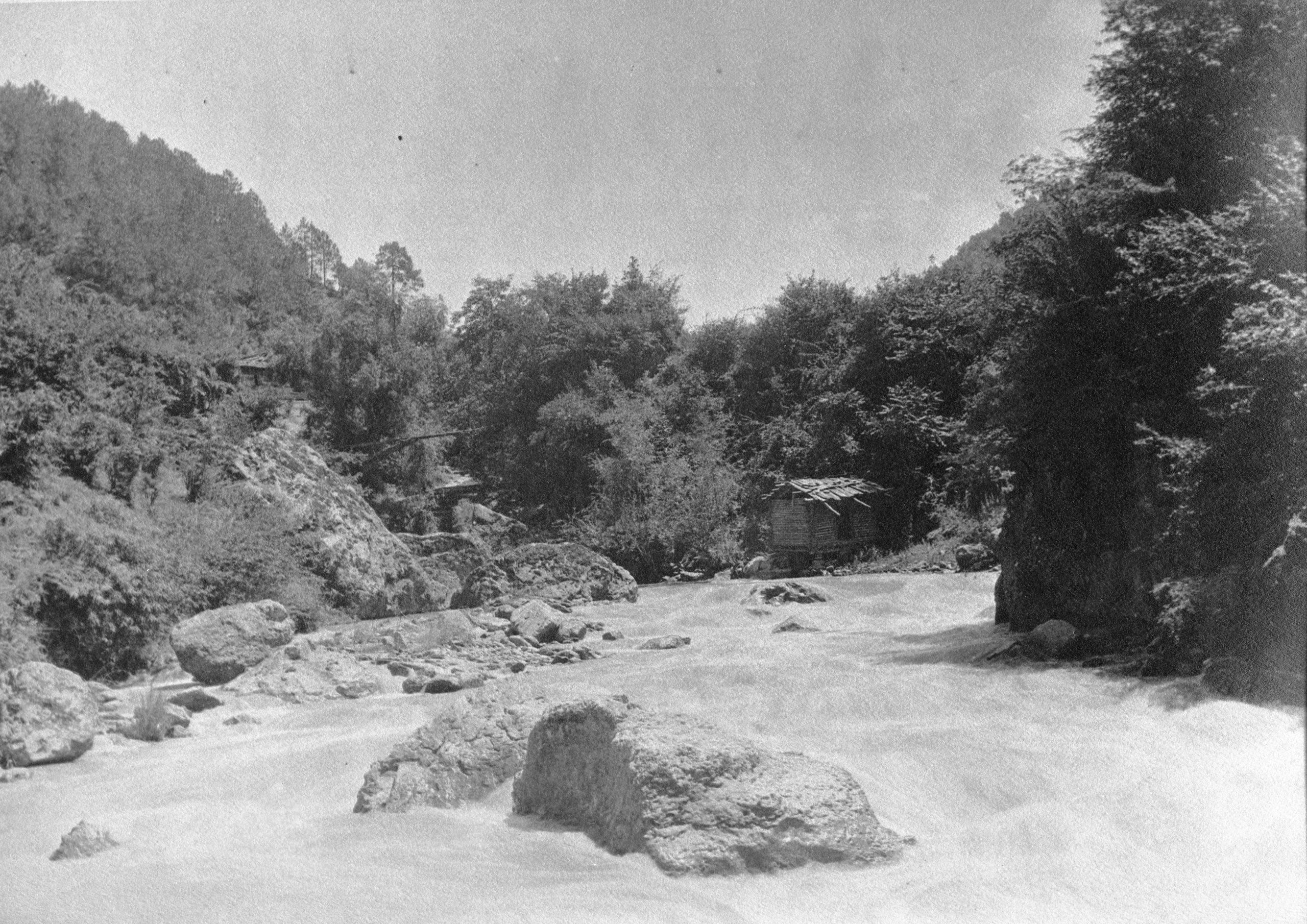

Along the Mekong to NW nearing Kang-pu

Along the Mekong to NW nearing Kang-pu

Ai Wa to their next stop, Kang Pu was 9½ miles. From Wei shi they were accompanied on the road by about 70 soldiers under two officers, who were also travelling to Atentze.

“They (the soldiers) are an awful nuisance as they take all the best accommodation at the stopping places. Fortunately they are staying a day at tomorrow night's halt, so we shall get a day ahead”.

“During the day’s journey, as I was tramping along ahead of our caravan I overtook one of the soldiers (their main body was on ahead). He had got a kind of dysentery and had been left behind to find his way to Kang Pu as best he could. After examining him, I gave him my pony to ride, and we travelled on to Kang Pu together. I later gave him some medicine for the dysentery. He was very grateful. Most of these ‘soldiers' are mere boys. They are provided with no protection from the weather. GP says this is disgraceful”.

That night for dinner at the inn in Kang Pu (5933 ft.) they had three courses - soup, chicken and potatoes and vegetable marrow and stewed fruit.

Day thirty-eight August 23rd, 1923 Kang Pu to Yueh Chih - 14½ miles

“Today we have had another day following up the left bank of the Mekong river. It was only a short stage today, 14½ miles. The country got wilder and the path lead alongside the river up narrow gorges between steep well-wooded hills, with only an occasional farm or patch of cultivation. At 4½ miles there was a steep climb of 800 feet, and then fine views to the north”.

“Three streams break through the mountains, the eastern stream piercing through a great wall of red and grey rock, showing high hills beyond with patches of cultivation, the work of Lisu. At 5½ miles the road descends to the river again and passes by the wonderful La-p'u-Lu rapid, which GP says are the wildest he has ever seen. Here the mighty Mekong, restricted to less than 40 yards in width, thunders through the gorge, the muddy waters in their wild career dashing against the rocks and being churned into great white waves”.

Breakthrough of a tributary of the R. Mekong coming through white limestone cliff

Breakthrough of a tributary of the R. Mekong coming through white limestone cliff

They did two-thirds of the distance to Siu Tong before lunch – having left at 7.40 a.m. they arrived at their lunch place at 11.15. HGT set off again with the Tibetan boy at 1.5 and arrived at about 3 p.m. after walking all the way. They had gone on ahead so as to get a place fixed before the caravan came up.

Hollow pillar for burning twigs etc to the Spirits of the Hills, one mile north of Kang-pu

Hollow pillar for burning twigs etc to the Spirits of the Hills, one mile north of Kang-pu

“One mile after leaving Kang Pu we came to a white hollow pillar, used for burning pine twigs, a Tibetan custom in connection with spirit worship and bones of their ancestors. Next to it was the usual pile of stones, a mani chorten and a prayer flag on a post".

Cliff road zig zagging upwards by Mekong between Kang-pu and Yueh Chi

Cliff road zig zagging upwards by Mekong between Kang-pu and Yueh Chi

After travelling 7 miles they climbed up the bank of the river to a height of about 500 feet. As the bank was too precipitous for the road, the path went zig-zagging upwards. At the highest point were another two white pillars with the usual om mane padme hum inscription. Then they decended again to the River.

“On the opposite bank there was a most striking example of a river breaking through two great vertical cliffs, of whitish stone, and a small clear river rushing between to join the Mekong”.

Breakthrough of the Mekong near Puh-ti

Breakthrough of the Mekong near Puh-ti

Ta-chiao tributary of the Mekong near Puh-ti

Ta-chiao tributary of the Mekong near Puh-ti

“Immediately after this we entered a wonderful gorge - with the La-p’u-Lu rapids. At this point, the great Mekong river narrowed down to about 40 yards passing between vertical walls of rock, with huge boulders in the bed.

“To see the great mass of water tearing through such a narrow channel - roaring and boiling, as if angry with the delay, was a sight not to be forgotten. The rapids were about ½ a mile long, and one had to shout to make oneself heard”.

They mistook a hillside village for Yueh Chih and went out of their way for about a mile, so had to hurry back to get to the proper place before the mules arrived, and they stopped for the night. Yueh Chih (5825 ft) was a village of fifty-five families, Chinese and Mosu.

Day thirty-nine August 24 1923 Yueh Chih to Pa-Ti - 20 miles

Another day nearer to Atentze – they had now gone 5 days out of the anticipated 9 days journey from Wei shi to Atentze – they thought they should arrive on August 28th.

They left Yueh Chih at 7.30. It was raining so HGT rode on the pony for a couple of miles, where the road passed through paddy fields and was very muddy and then when the rain was practically over, he walked the rest of the way - Total distance 20 miles.

“During the morning, we passed some Lisu working in the fields and one woman had a curious head-dress with about 3 rows of cowrie shells. Half an hour later I saw a little girl with a similar head-dress, but covered with cowrie shells and little straw tassels hanging down at the back. I reckoned that there were about 300 shells. On enquiring we found that this is quite a common head-dress amongst the Lisu families about here. The shells come from Burma and cost 100 to the tael - Frequently 700 are used, which would mean it costed about 10 dollars”.

A Li Su family and child with cowrie shell head-dress

A Li Su family and child with cowrie shell head-dress

“Most of the Lisu women carry and smoke a pipe with a long thin stem and a big wooden bowl. I gave the little girl a little cash and persuaded her father and mother to stand for a photograph - after showing them the picture in the view finder”.

“We stopped for lunch at Puh-ti on the banks of the Mekong, and just before reaching there, being on ahead, I caught up to a Chinese man and chatted with him. I found that he had been in the employ of the French merchant at Atentze and he gave us much information about the road etc."

“The trouble up near Batang was now over, that it was as we had heard before, fighting between the two lamas - -Kang K’a lama and Lan K'a lama. That Kang K'a lama had come out top and that now they had made peace. The fighting took place in the Chinese 4th month - we reckoned that this was probably early in June, and this was probably about the time Mr. Weatherbe was up there. Hence this was most likely the reason why he was turned back.”

“As peace is now made we hope that things will be alright when we get there”.

"At Puh-ti, 13½ miles from Yieh Chih, we bought two fresh fish (probably carp) and had one right away for lunch. It was delicious. We had the other for dinner that evening”.

Leaving Puh-ti at 2.15 they pushed on and arrived at Pa-ti (6,095 ft.) after 6½ miles at 4.35 p.m. There were no Chinese in this village, which has only 6 or 7 families - all Mosu. They stayed in a Mosu home.

"The women wore a big pleated apron - a heavy looking turban with a silver rosette like ornament, often with a coloured stone in the centre of the rosette, and somewhat to one side, (the right side) above the forehead. Big earrings with pendants with coloured stones gave them quite an attractive appearance".

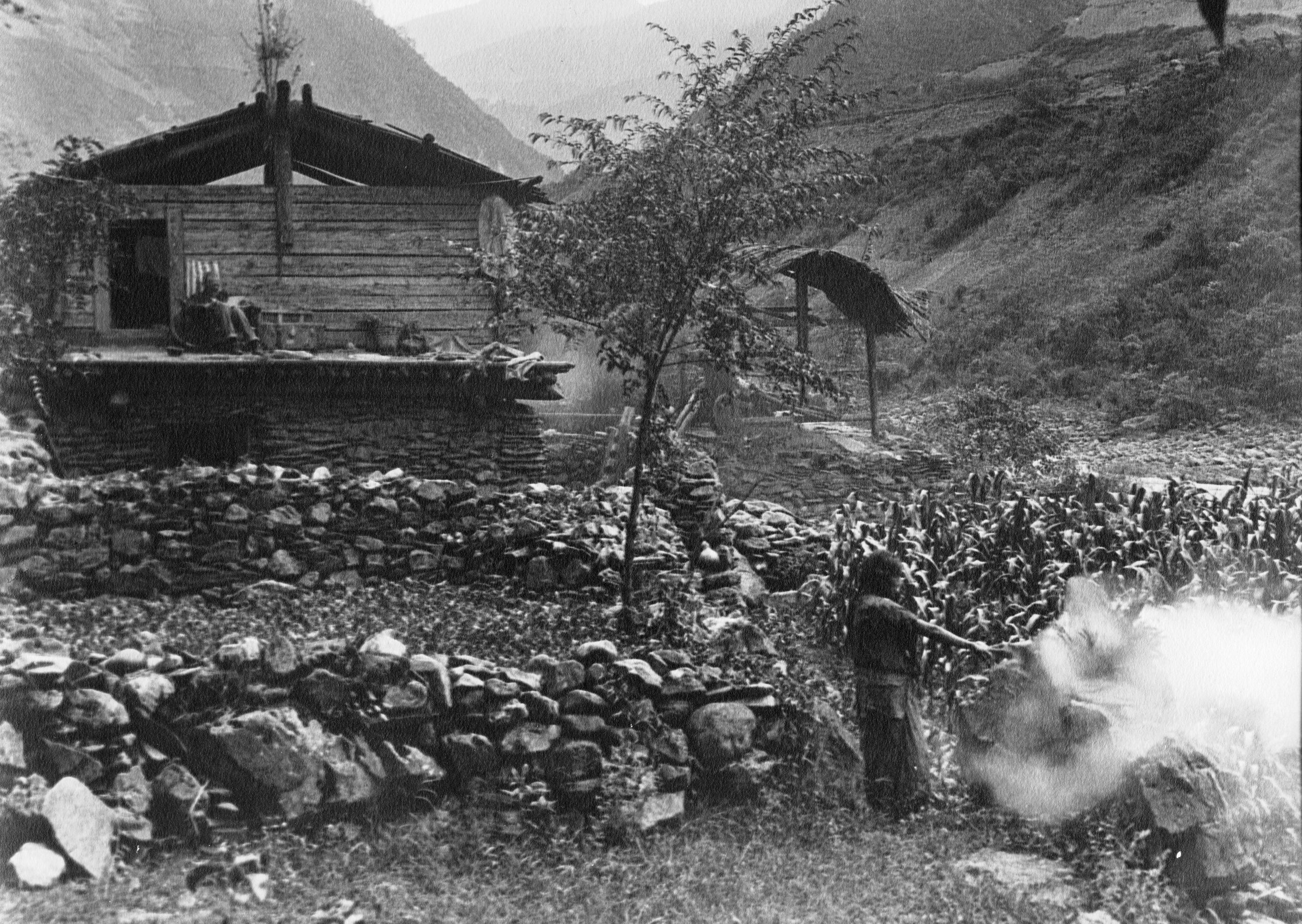

A Mosu home and kitchen in Pa-ti

A Mosu home and kitchen in Pa-ti

“I saw 3 or 4 patients and then got permission to take a flashlight photo, which I hope will give a better idea than words what this remarkable place is like.

“It is a big place with a log wall. In the centre a pillar with a few dried pine branches fastened round, meant as an offering to the kitchen spirit. Up in one corner a little shrine, with a god and bowls for incense sticks &c., In the centre of the room a big open fire place with 3 copper tripod stands, with shut legs to support pots or pans over the fire. In one corner - a huge copper water tank about 3 feet in diameter. Around the wall, on two sides, a raised place, like a big continuous dresser, the same height as the fire place and about 4 ft. wide, on which the family can sleep near the fire in winter”.

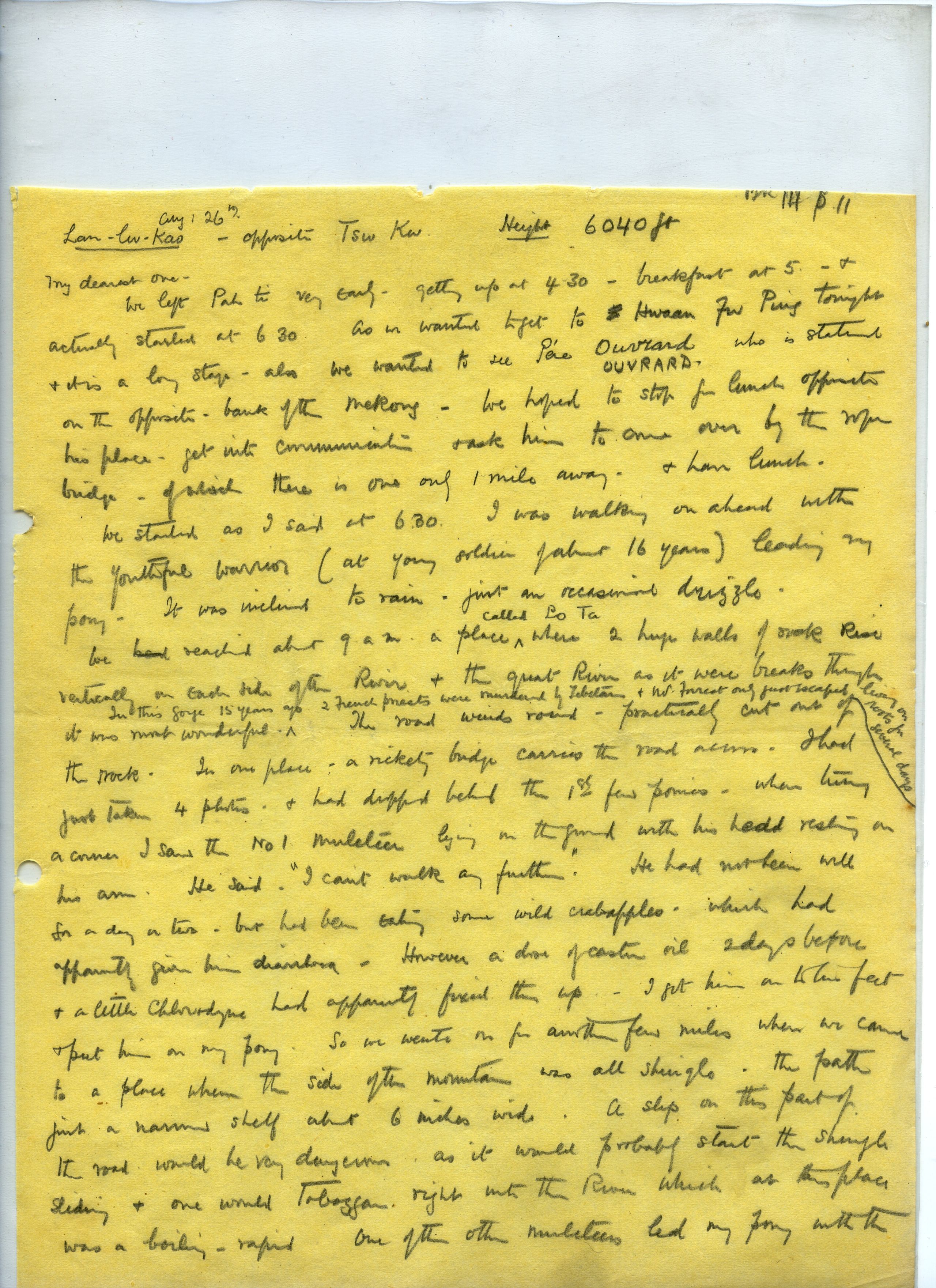

LAH- lu-Kao (opposite Tsu Ku) Height 6040 ft.

August 26th.

My dearest one,

We left Pah-ti very early, getting up at 4.30, breakfast at 5 and actually started at 6.30. as we wanted to get to Hwaan Fu Ping tonight and it is a long stage - also we wanted to see Père Ouvraad who is stationed on the opposite bank of the Mekong. We hoped to stop for lunch opposite his place, get into communication and ask him to come over by the rope bridge - of which there is one only 1 mile away - and have lunch.

We started as I said at 6.30, I was walking on ahead with the youthful warrior (a young soldier of about 16 years) leading my pony. It was inclined to rain, just an occasional drizzle.

We reached about 9 a.m. a place called Bo Ta where two huge walls of rock rise vertically on each side of the river, and the great river as it were breaks through - it was most wonderful.

In this gorge 15 years ago two French priests were murdered by Tibetans and Mr. Forrest only just escaped - living on roots for several days. The road winds round, - practically cut out of the rock. In one place a rickety bridge carries the road across.

I had just taken 4 photos and had dropped behind the first few ponies when turning a corner I saw the No.1 muleteer lying on the ground with his head resting on his arm. He said "I can't walk any further". He had not been well for a day or two, but had been eating some wild crab-apples which had apparently given him diarrhoea. However, a dose of castor oil two days before and a little chlorodyne had apparently fixed him up. I got him on to his feet and put him on my pony. So we went on for another few miles, when we came to a place where the side of the mountain was all shingle, the path just a narrow shelf about 6 inches wide. A slip on this part of the road would be very dangerous, as it would probably start the shingle sliding and one would toboggan right into the river, which at this place was a boiling rapid. One of the other muleteers led my pony with the sick man and I was walking immediately next, when I saw him swaying in the saddle. I managed to reach him and gave him a hard punch in the back and said "Ride properly, ride properly". This pulled him together and we went over a number, I should think about 15 of them, most dangerous places. At one spot my left foot slipped and away down went part of the road and a lot of shingle. Then the mules and ponies had to climb over smooth rocks with the path also only about 6 inches wide, again and again I saw the sick man swaying and I shouted to him to ride properly. As soon as the path widened a little I caught him up and he apparently did not know what he was doing, for when I spoke to him he took no notice, but mechanically tried to urge the pony on.

We kept on, and at 1 o'clock, after 6½ miles continual travelling we were within ½ a mile of our halting place, when suddenly the sick Tibetan muleteer swayed - I shouted, but over he went. Fortunately there was no loose shingle and although he went off the pony and over the edge, his foot caught in the stirrup and the muleteer leading the pony sprang back and I ran forward and we grabbed his leg and hauled him on to the path. If it had happened on the shingle I don't think anything could have saved him. He would have tobogganed Into the Mekong and that would have been the end of him.

We stopped - got out the medicine chest and tried to dose him up, but he refused to take even water, and obviously had a temperature and was wandering. He tried to stand up, but the muleteer and I tried to hold him down, till the other mule drivers came up. Poor chap he is a huge big built man, and he kept trying to get up - so that I had to trip him up and throw him down, and the two of us practically sat on him till he was quiet. As we were almost opposite Père Ouvraad's place we came on and the other muleteers carried the sick man. After a lot of shouting across the river, one of Père Ouvraad’s servants came across by the rope bridge which is about a mile down the river. He said that the French priest, Père Ouvraad was away, but he was due back tomorrow. So as there is a peasant's cottage just here we have decided to stay the night. I have dosed the man up with hypodermic quinine, and we hope he will he fit to travel in the morning - a litter is being made to carry him on, and provided he is quiet I think we shall manage to get along. If impossible we will wait a day, see Père Ouvraad and get him to look after him - but we want to get on if possible.

I am so looking forward to getting a letter at Atentze and perhaps a telegram. I arranged with Mr. Klaver to send the next mail on to Atentze and if it misses us there we shall get it at Batang.

I have just been down to a small rivulet and had a tub, and having had dinner we shall soon be in bed. I wish you could see this log hut, the roof is open at the ends and the wooden boards which take the place of tiles do not meet in the centre, where there is a gap of about a foot - provided it does not rain tonight it will be alright - but if it rains ...... well we must put up with it.

Good night!!

Day forty August 25th. Pa-Ti to Lan-Lu-K’a (or Na-lon-k’a) (opposite Tse Ku) - 19 miles

They left Pa-ti very early, getting up at 4.30 a.m., breakfast at 5 and actually started at 6.30. as they had wanted to get to Hwaan Fu Ping (6,040 ft.) that night and it was a long stage.

“We want to see French priest Père Ouvraad who is stationed on the opposite bank of the Mekong. We hope to stop for lunch opposite his place which is accessible by a rope”.

“I was walking on ahead with the young man I call the youthful warrior (a young soldier of about 16 years) leading his pony. It was inclined to rain, just an occasional drizzle. The country was now wilder. The hills were steep and well-wooded and the road passed through some grand gorges. At about 9 a.m. they reached a wonderful place called Bo Ta where the river broke through rocky cliffs - two huge walls of rock 500 to 700 feet in height rose vertically on each side of the river”.

Bridge at Bo Ta on defile by R Mekong near Hwan-fu-ping

Bridge at Bo Ta on defile by R Mekong near Hwan-fu-ping

“In this gorge 15 years ago two French R.C. priests were murdered by Tibetans and a botanist Mr. Forrest only just escaped - living on roots for several days. The road wound around, - practically cut out of the rock. In one place a rickety bridge carried the road across”.

“I had just taken some photos and had dropped behind the first few ponies when turning a corner I saw the No.1 muleteer lying on the ground with his head resting on his arm saying "I can't walk any further". He had not been well for a day or two, but had been eating some wild crab-apples which had apparently given him diarrhoea. However, a dose of castor oil two days before and a little chlorodyne had apparently fixed him up. I got him on to his feet and put him on my pony”.

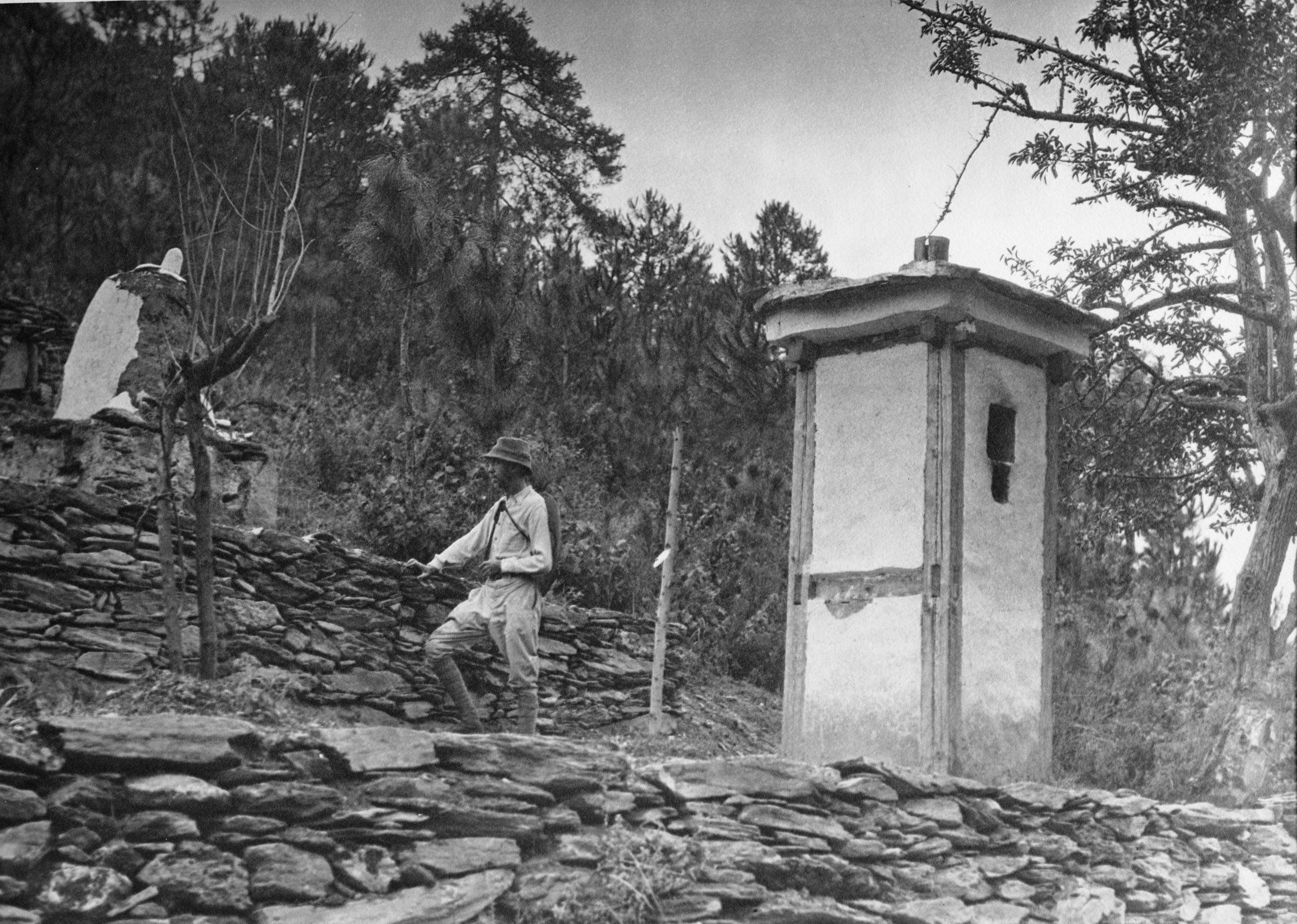

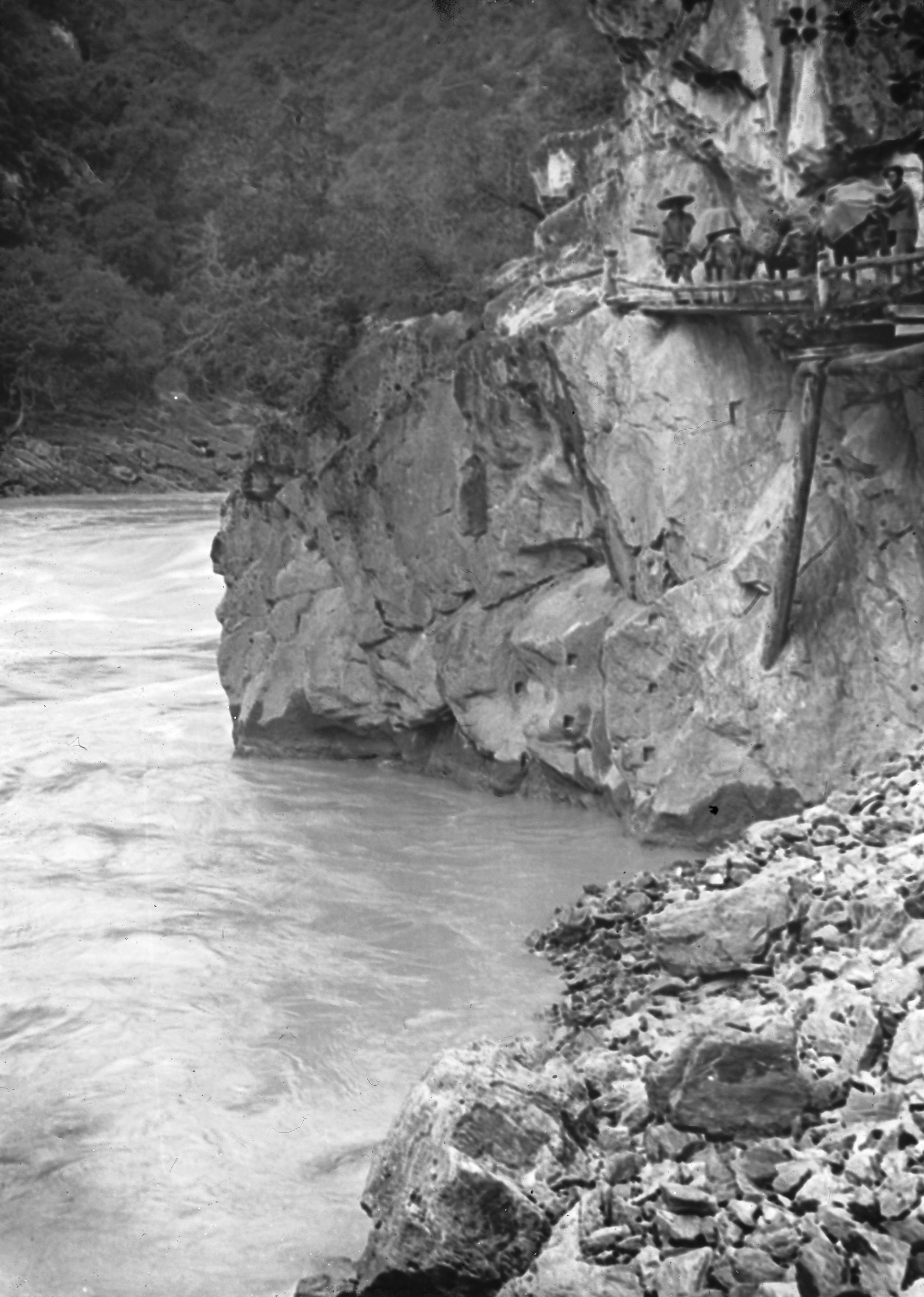

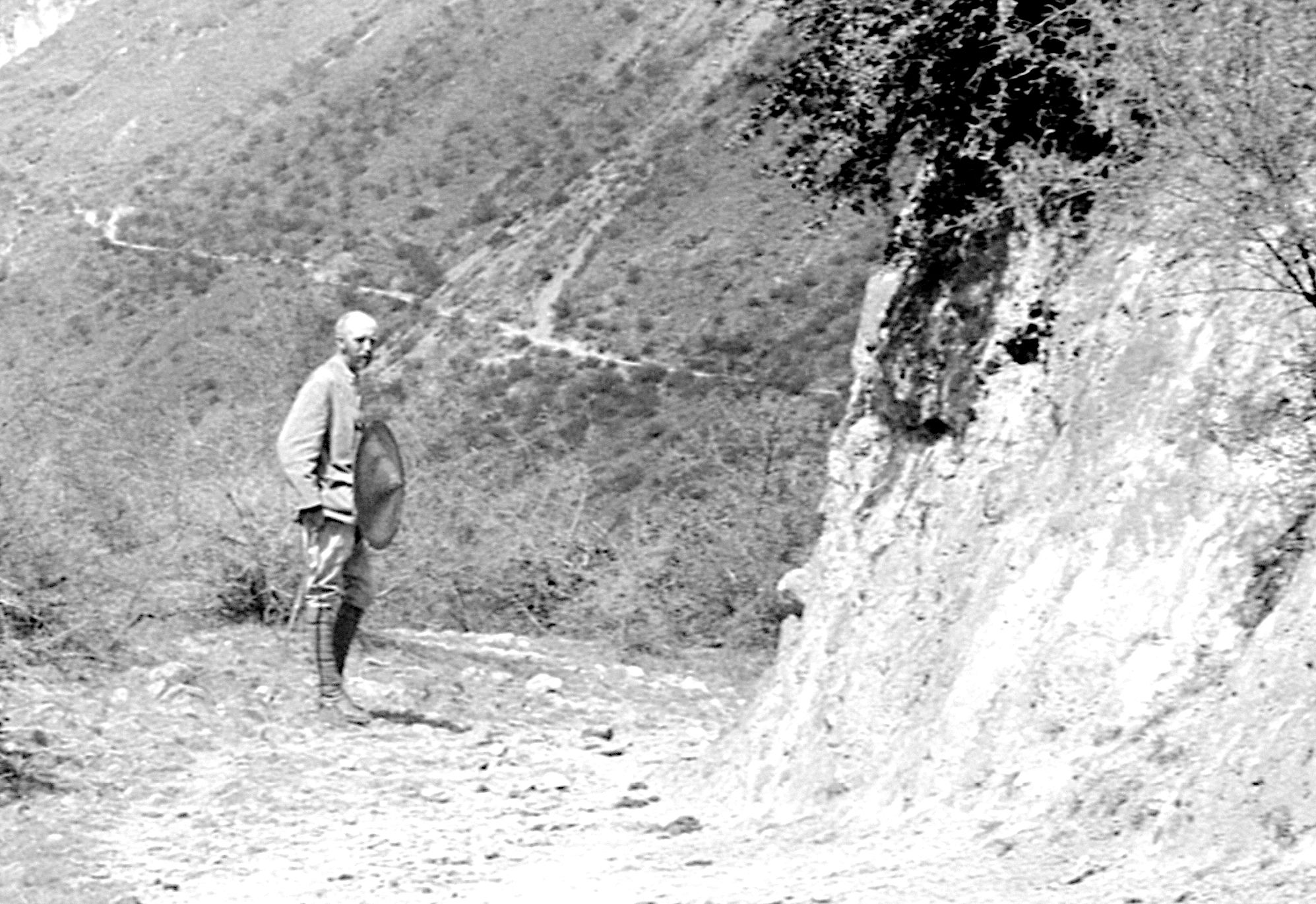

“We went on like this for another few miles, until we came to a place where the side of the mountain was all shingle, the path just a narrow shelf about 6 inches wide in places. A slip on this part of the road would have been very dangerous, as it would probably have started the shingle sliding and one would toboggan right into the river, which at this place was a boiling rapid”.

HGT on just a narrow shelf path by the Mekong river

HGT on just a narrow shelf path by the Mekong river

“One of the other muleteers led the pony with the sick man and I was walking alongside. When I noticed that he was swaying in the saddle, I managed to reach him and gave him a hard punch in the back and said "Ride properly, ride properly". This seemed to pull him together and we went over a number, about 15 of them, of very dangerous places”.

“At one spot my left foot slipped and down went part of the road and a lot of shingle. The mules and ponies then had to climb over smooth rocks with the path only about 6 inches wide. Again and again I saw the sick man swaying and shouted to him to ride properly. As soon as the path widened a little I caught him up and spoke to him. He took no notice and didn’t seem to know what he was doing, but mechanically tried to urge the pony on”.

“We kept on and at 1.00 p.m, after 6½ miles continual travelling, we were within ½ a mile of their halting place, when suddenly the sick Tibetan muleteer swayed and over he went. Fortunately there was no loose shingle and although he went off the pony and over the edge, his foot caught in the stirrup. The muleteer leading the pony sprang back and I ran forward. We grabbed his leg and hauled him on to the path. If it had happened on the shingle nothing would have saved him. He would have tobogganed into the Mekong and that would have been the end of him”.

“I got out the medicine chest and tried to dose him up, but he refused to take even water, and obviously had a temperature and was wandering. He tried to stand up, and the muleteer and I tried to hold him down, till the other mule drivers came up. Poor chap, he is a huge big-build man, and he kept trying to get up - so that I had to trip him up and throw him down, and the two of us practically sat on him till he was quiet”.

As they were almost opposite Père Ouvraad's place at Tse-ku they carried on, with the other muleteers carrying the sick man. After a lot of shouting across the river, one of Père Ouvraad’s servants came across by the rope bridge which was about a mile down the river.

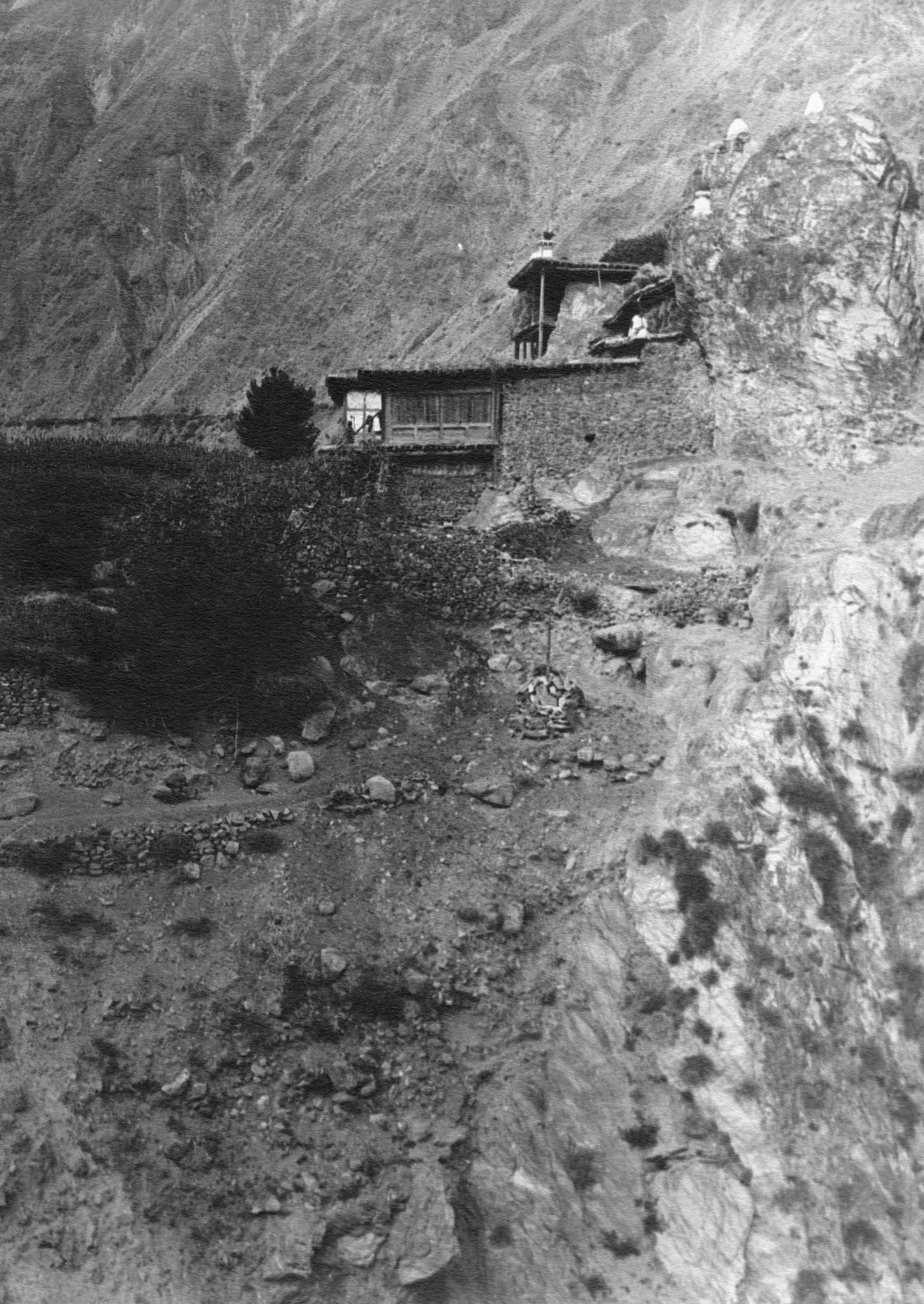

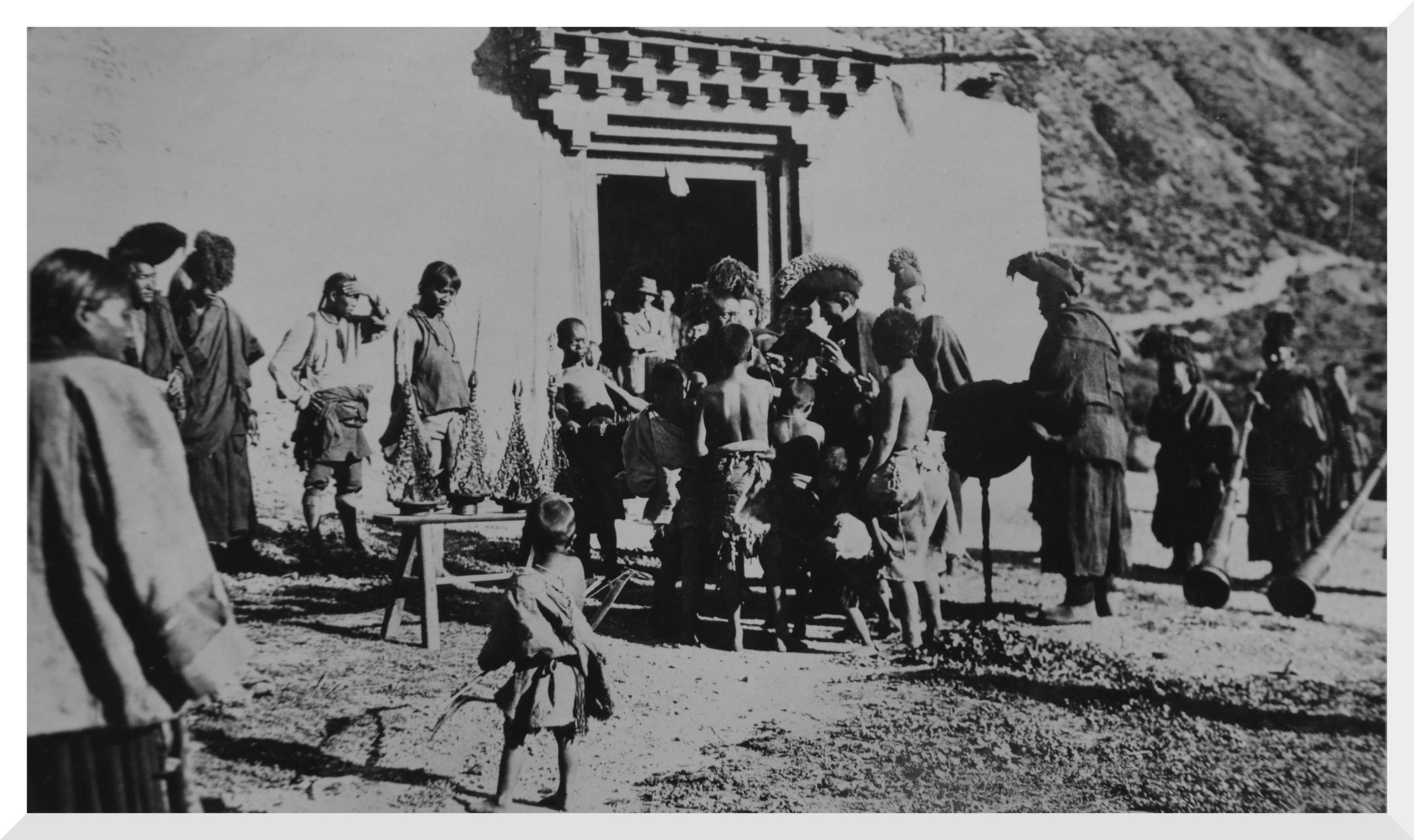

Peasants' cottage at Lan-lu-k'a giving a fire offering to the spirits of the hills

Peasants' cottage at Lan-lu-k'a giving a fire offering to the spirits of the hills

The French priest, Père Ouvraad was away, but due back the following day, so they decided to stay the night at Lan-lu-k’a (6,040 ft.) - opposite Tse-ku - as there was a peasant's cottage where they could stay.

“I dosed the man up with hypodermic quinine, and hoped he would be fit to travel in the morning. A litter was made to carry him on, and provided he was quiet I think we shall manage to get along. If impossible we will wait a day, see Père Ouvraad and get him to look after him.

Day forty-one August 26th, 1923. Lan-lu-k’a

“The sick man was no better in the morning so we decided to wait over today and see Père Ouvraad late afternoon. I spent the morning down by a beautiful little brook close by, developing 3 films, and washing through two shirts, pants and socks. It is a lovely day. We hung out our washing and the films which have come out well are nearly dry”.

“In the afternoon we saw Père Ouvraad and fixed up with him to look after the sick man – I think he will either be dead or better within 4 or 5 days”.

HGT noted that Père Ouvrard was himself suffering from malaria. His parish extended some 89 miles to the south to Yeh-chih and on the north nearly to Yakalo. He had 622 baptized Christians, of whom over 400 were Tibetans and the rest mostly Chinese. A few were Mosu. He said the tendency in these parts was for the Chinese to become Tibetanised.

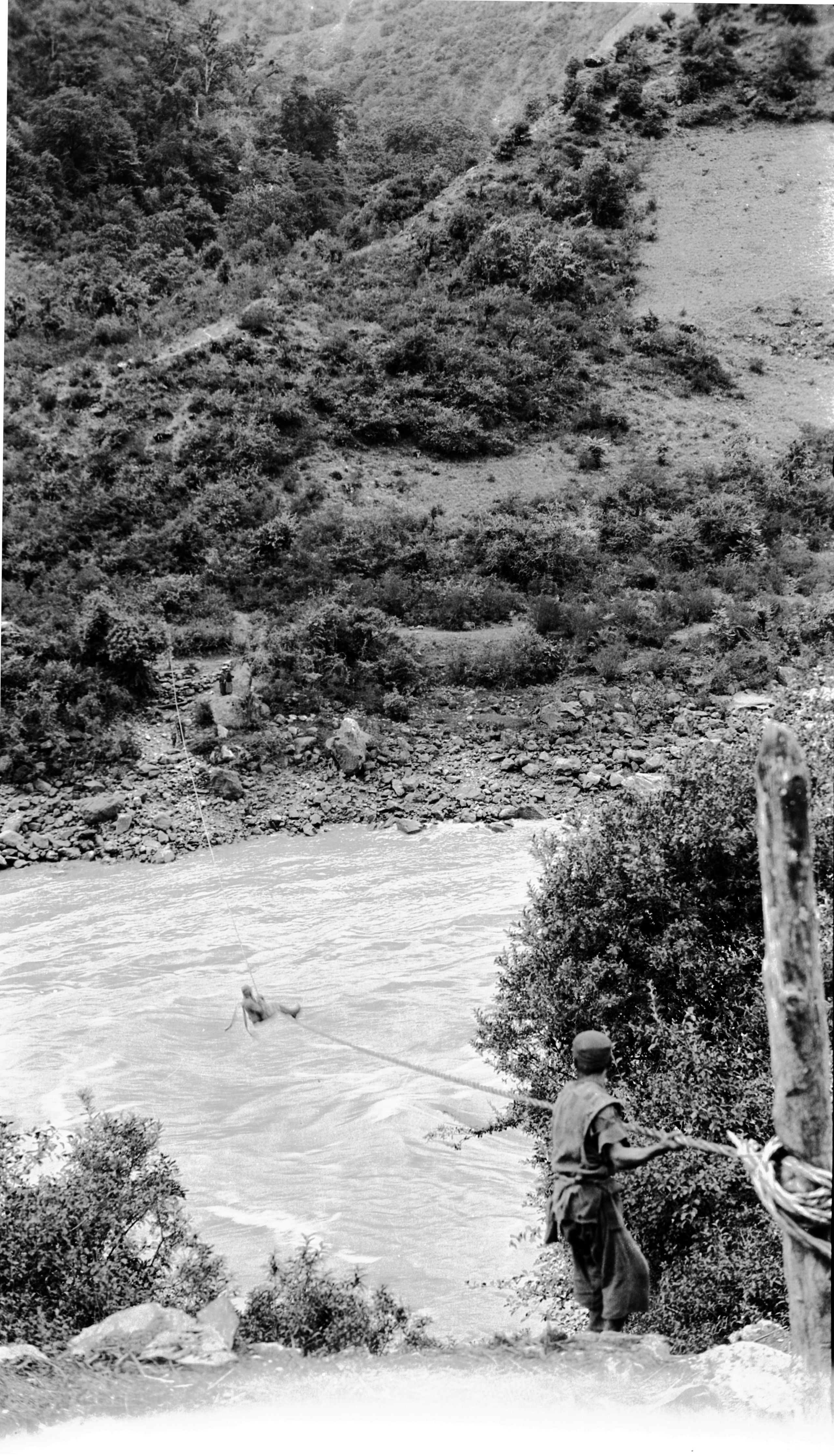

GP crossing the river by rope bridge sitting on the knees of a Tibetan

GP crossing the river by rope bridge sitting on the knees of a Tibetan

They crossed the river by the rope bridge. It was now 7 o'clock and on reaching the rope bridge it was dark - except for a little moonlight. GP went over with a Chinese to whom he clung, and the two were slung together on to the slider.

“I got a snapshot of them half-way across. I waited till there was a distant shout, a rumble on the bamboo rope, and the General appeared in sight, hanging on to his companion for dear life!!!. Then it was my turn”.

HGT preparing to cross the rope bridge

HGT preparing to cross the rope bridge

HGT ½ way across the Mekong on the rope bridge

HGT ½ way across the Mekong on the rope bridge

“It was most weird to be launched out into the darkness over the rushing river - and to be hanging like this”:-

HGT's sketch of the rope crossing

HGT's sketch of the rope crossing

“I was trussed up with a leather band under one's thighs and then over one shoulder and under the other arm. Then with the word “Go” one was launched off the edge of the cliff and went sliding down over the river. About 15 yards from the opposite bank one stopped and had to haul oneself along, hand, over hand”.

Day forty-two August 27th, 1923. Lau-lu-k’a to Hwan-fu Ping - 5 miles

The Ma-fu-tao died at 4 a.m. - malignant malaria. This was a severe form of malaria prevalent along the Mekong valley, which the Chinese called the "chang chih", and which was generally very rapidly fatal.

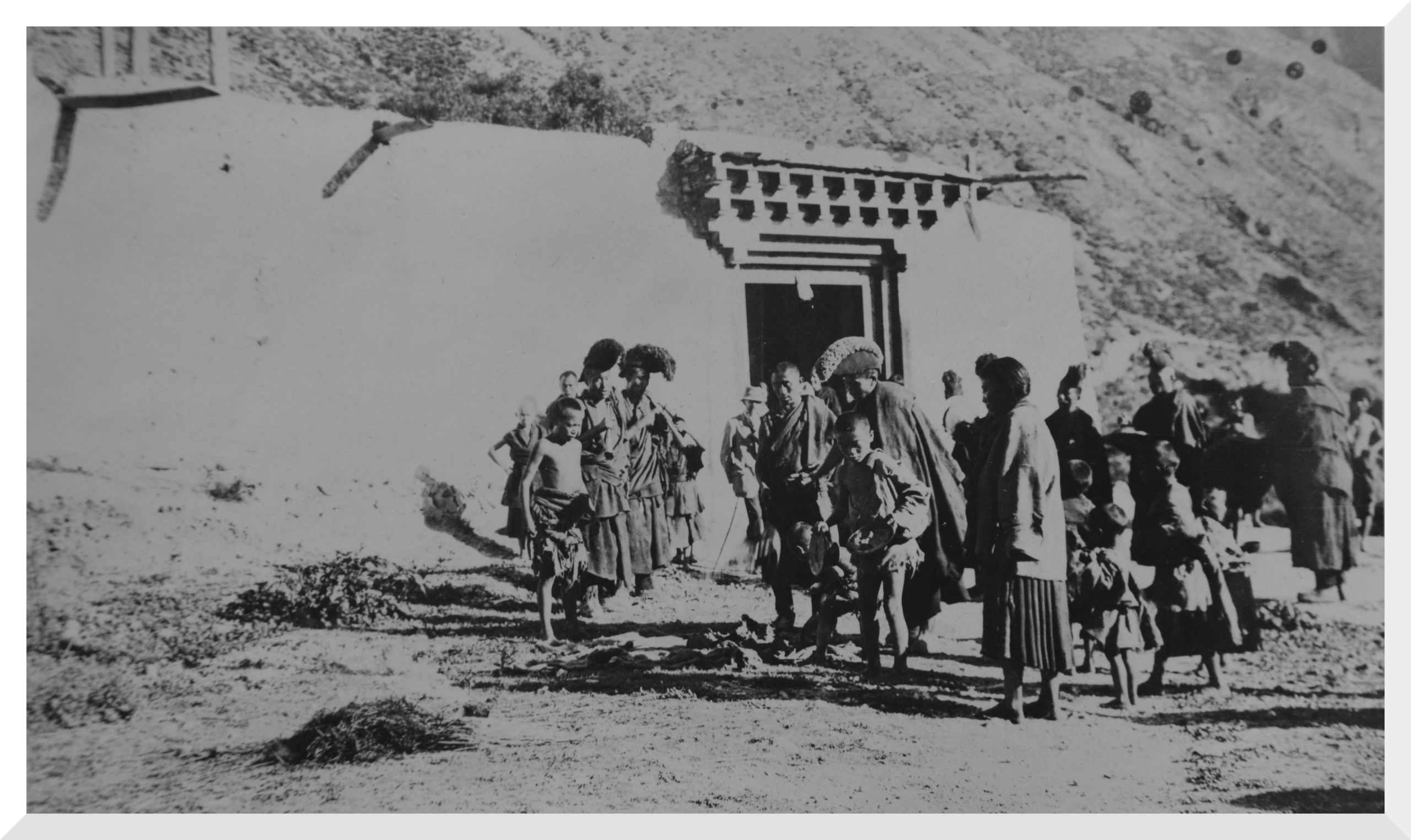

“The previous afternoon, Père Ouvraad had turned up with a couple of patients – which is very opportune. It is a most extraordinary set of circumstances - the Ma-fu-tao, the head muleteer who had been walking and riding the pony 36 hours ago is now dead. Breaking down just opposite the R.C. Mission meant we have all the advantage of Père Ouvraad’s help. Père Ouvraad can both speak and write Tibetan and this was a great help as he can get a certificate written in Tibetan to say he died from sickness and had not been murdered”. .

“We buried the Ma-fu-tao at 12 o'clock mid-day. Père Ouvrard said that the Tibetans usually bury the corpse temporarily, and when decomposed dig it up, burn the bones in a vase and bury them again. The poorer either take the corpse on to the hills to be devoured by wild animals or else dump it in the Mekong. If it sticks on the rocks, they push it off again lest the Christians take it up for re-burial!”

They set off again at 1.30 p.m. On the road and very glad to get away. They decided to only do a very short stage of 15 li and arrived at the village of Hwan-fu Ping (6,144 ft.) a village of sixteen families, at 3 p.m. They had tea – HGT developed a film and was just going to write his journal when he was asked to see a patient. He saw him and immediately there was a crowd of other patients and he had to go on till it was too dark to see. Altogether he saw about 25 and in this village there were only 16 families.

Day forty-three August 28th, 1923. Hwan-fu Ping to Yang Cha - 16 miles

“It seemed as if we were never going to get off from Hwan Fu Ping”.

“The Tibetan muleteers had driven their ponies out on to the hillside for the night, and in the morning, 5 of the 25 were missing. They were off up the hills, hunting everywhere, and at last brought in 4, but still there was one wanting. Just as we thought we should have to tell them to start with one short he was spied away up on the brushwood. The Tibetan villagers on their housetops had spied him (the house tops are flat) and away went one of the muleteers up the steep hillside, directed by shouts from the men on the house roof till at last in came the runaway”.

The result was instead of starting at about 7.00 a.m. they did not leave till 10 minutes to 10. They agreed to go right through without a mid-day halt. HGT put a couple of pears, 3 bread cakes and a stick of chocolate in his pocket and ate them at 1 o'clock. They got into Yang cha (in Tibetan La-dze) at 4.10. The mules did not arrive till 5, so it was a good thing that it was decided not to halt at mid-day, for these halts meant stopping for at least two hours. One of the mules had broken down but they managed to carry the load in.

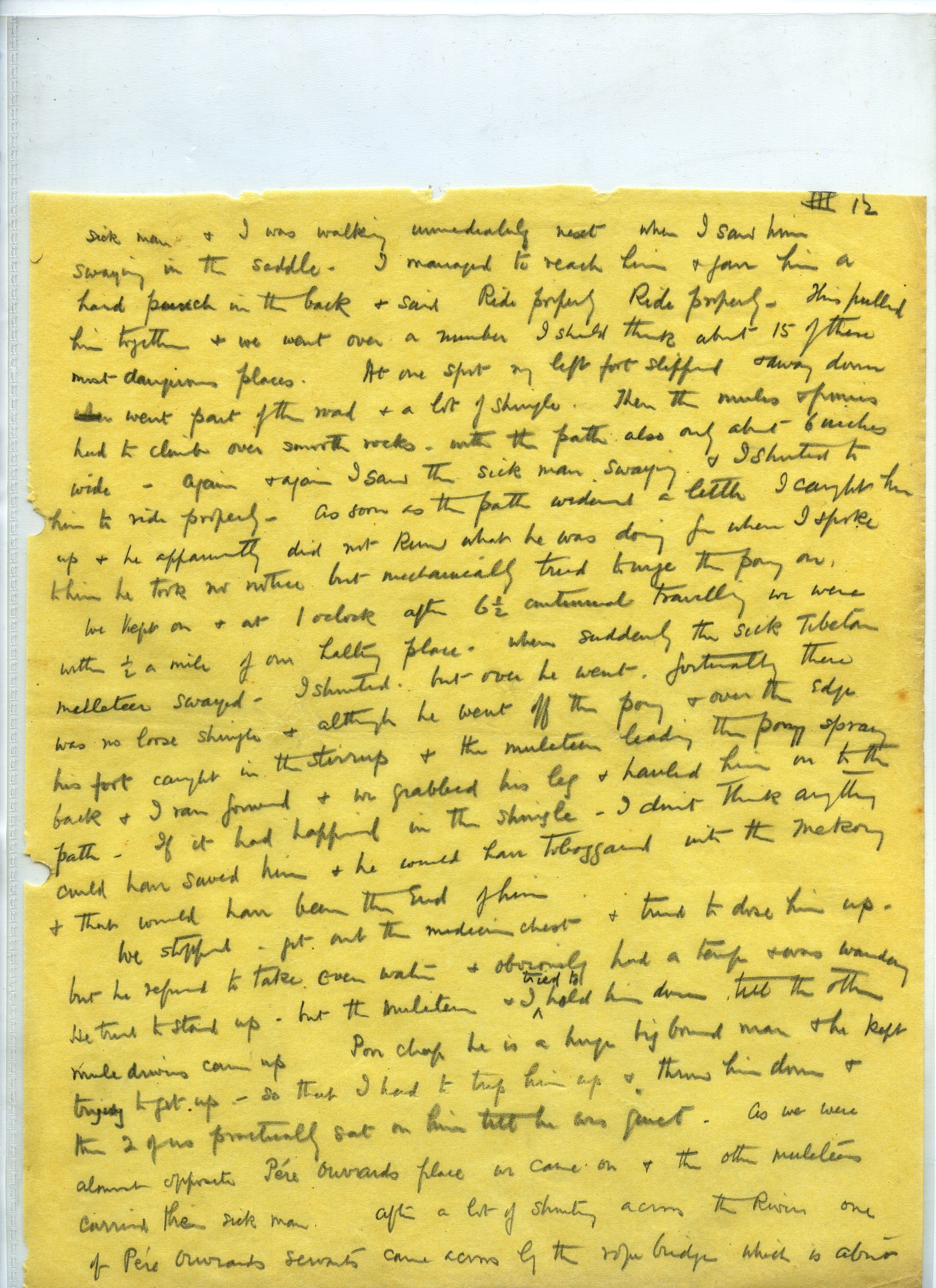

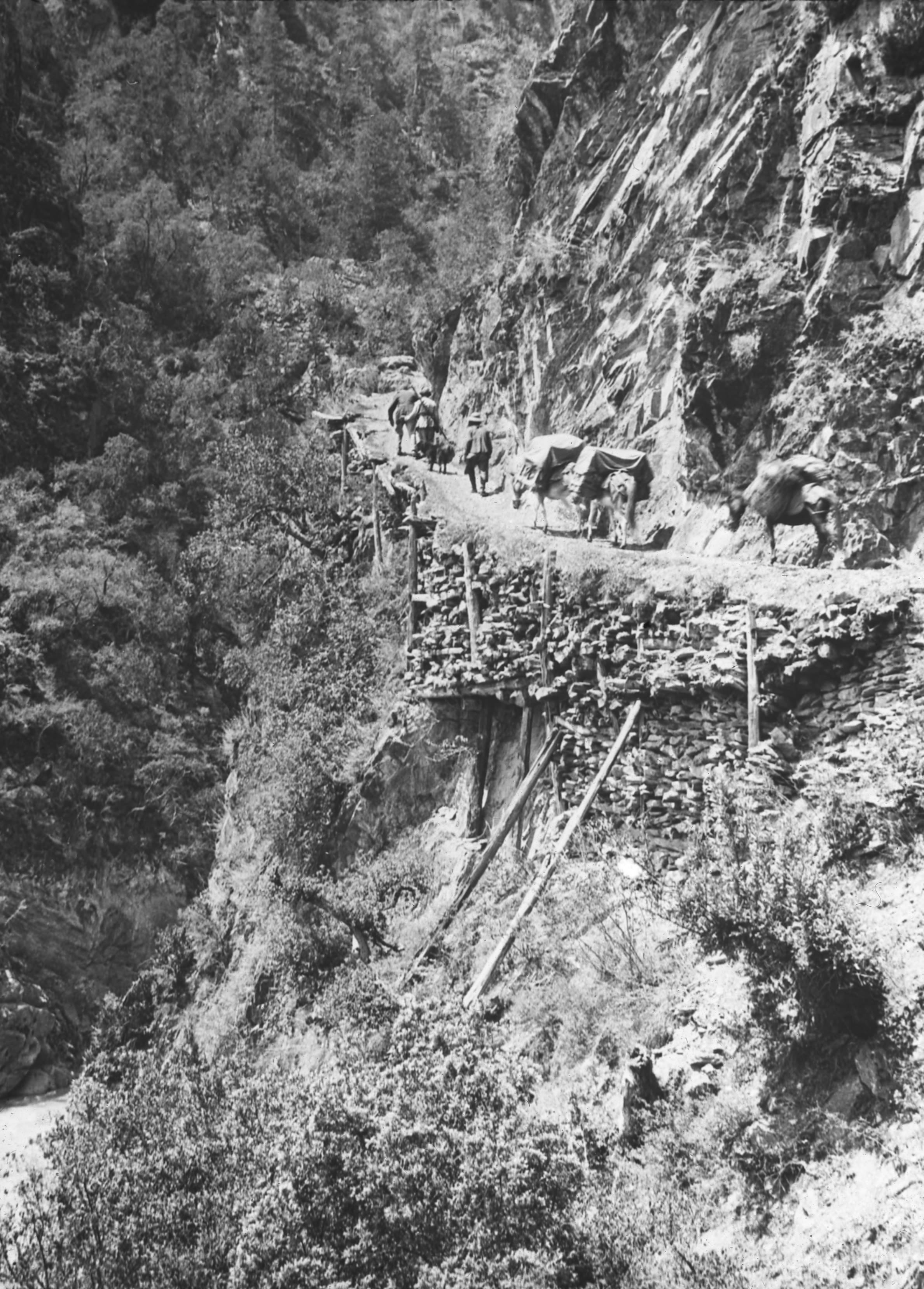

The gorge and the road alongside the Mekong between Hwan fu-peng and Yang cha

The gorge and the road alongside the Mekong between Hwan fu-peng and Yang cha

Another view of the gorge and the road alongside the Mekong between Hwan fu-peng and Yang cha

Another view of the gorge and the road alongside the Mekong between Hwan fu-peng and Yang cha

“The road today was absolutely wonderful. About noon we entered a great ravine, which looked as if it were a gateway of rock on a huge scale, the rock on each side rising vertically from the river to a height of about 500 feet and above this, more steep heights clothed with pines. The road crept round the face of this rock, in some places supported on trestles, and at several of the corners the muleteers stood on guard and gave each mule a pull in to the rock for the outer edge of the path was only supported by rather rotten looking lengths of pine with the bark still on”.

Final view of Mekong gorge between Hwan Fu Ping and Yang Cha

Final view of Mekong gorge between Hwan Fu Ping and Yang Cha

“In one place the road was again just a hand span wide, and a slip by a mule would have meant straight down to the river Mekong. After passing through this ravine we still followed the river’s windings. Its appearance seems to alter and all along the edge of the river bank are beautiful firs and cypresses. We have arrived at Yang Cha (6366 ft.) which has the Tibetan name of La Dza. It has five families, all Tibetan”.

That night they put up in a real Tibetan home. All along this road they kept meeting Tibetans, and only saw two Chinese all the way today.

“They seem a very happy lot of people and return our salutations with a delightful smile, and turning the hands up, and often putting out the tongue. The men wear long felt boots reaching nearly to the knees - decorated in colours - trousers are often decorated with a red pattern. Then they have a sackcloth coat, which they drop down to the waist if the weather is hot, and the belt with their flint and tinder box - sheathed Jack knife, pipe, bowl, gimlet and other odds and ends”.

“We passed several rope bridges and in two places there was an additional rope with prayer flags attached - with the words "om mane padme hum" repeated over and over again. I asked a Tibetan who overtook us what it was for. He beckoned to the sky and told me in sign language that they wanted rain very badly. The crops of maize are very late and Père Ouvraad fears that in some districts there will be a famine as the wet season is nearly over and the crops have not developed for want of rain”.

All these Tibetan houses - either on the flat roof, or just nearby - had a kind of brazier on a 4-legged stand in which each morning they would burn some twigs and leaves, which would give off a lot of smoke, as an offering to the spirits of the mountains.

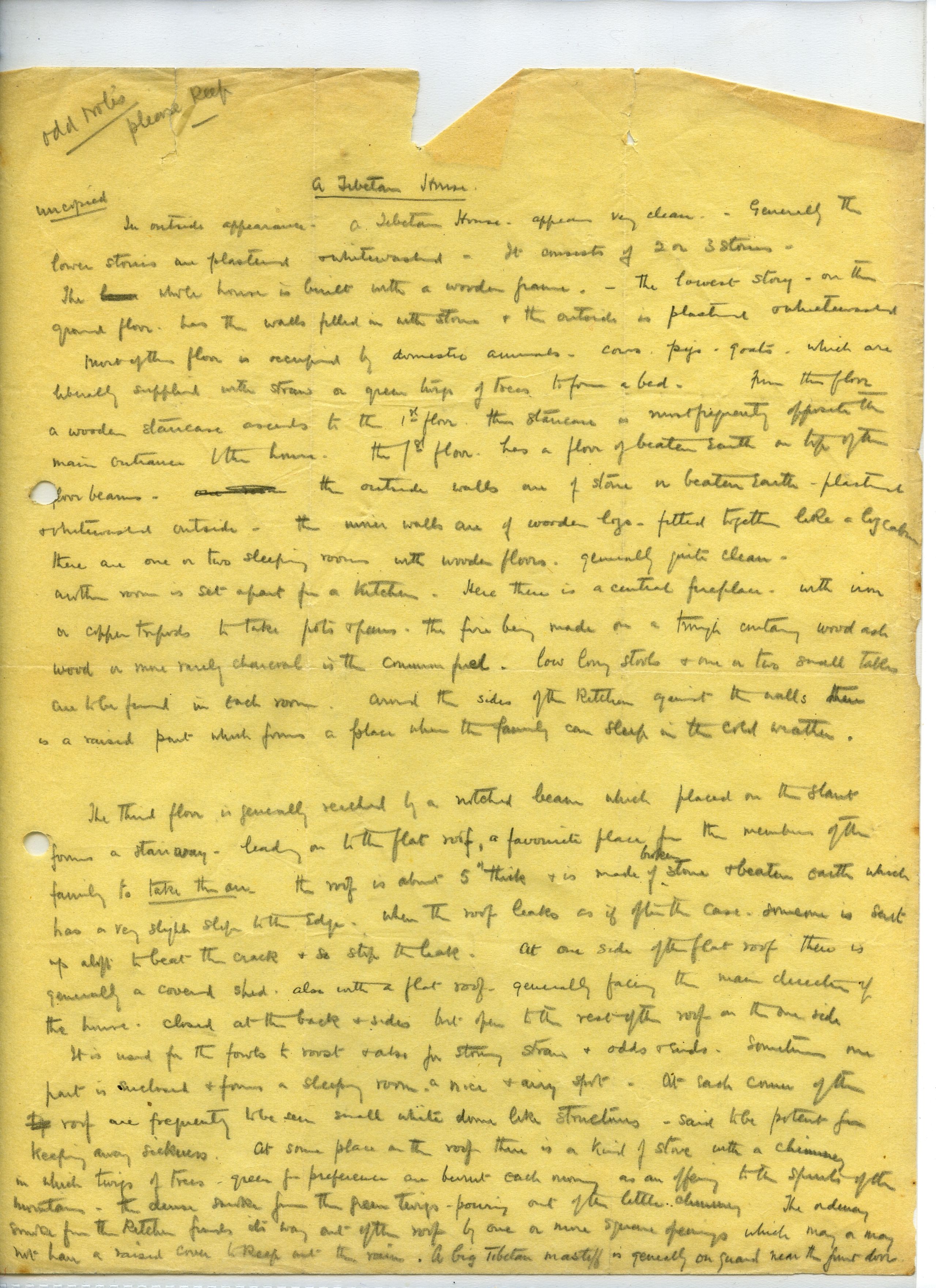

Odd notes

A Tibetan house

In outside appearance the Tibetan house appears very clean generally the lower stories are plastered and whitewashed. It consists of two or three stories –

The whole house is built with a wooden frame – the lower story on the ground floor has the walls filled in with stone and the outside is plastered and whitewashed. Most of the floor is occupied by domestic animals, cows, pigs and goats which are usually supplied with straw or green twigs of trees to form a bed.

A wooden staircase ascends to the first floor. This staircase is most frequently opposite the main entrance to the house. The first floor has a floor of beaten earth on top of the floor beams. The outside walls are of stone or beaten earth, plastered and whitewashed. Outside, the inner walls are of wooden logs fitted together like a log cabin. Where there are one or two sleeping rooms with wooden floors generally quite clean. Another room is set apart for a kitchen. Here there is a central fireplace with iron or copper tripods to take pots and pans. The fire being made on a trough containing wood ash. Wood, or more rarely charcoal, is the common fuel. Long low stools and one or two small tables can be found in each room. Around the sides of the kitchen, against the walls, there is a raised part which forms a place where the family can sleep in the cold weather.

The third floor is generally reached by a notched beam which, placed on the slant, forms a stairway leading on to the flat roof - a favourite place for the members of the family to take the air. The roof is about 5 inches thick and is made of broken stone and beaten earth which has a very slight slope to the edge. When the roof leaks as is often the case someone is sent up aloft to beat the crack and so stop the leak. At one side of the flat roof there is generally a covered shed, also with a flat roof, generally facing the main direction of the house - closed at the back and sides but open to the rest of the roof on the one side. It is used for the fowls to roost and also for storing straw and odds and ends. Sometimes, one part is enclosed and forms a sleeping room – a nice airy spot. At each corner of the roof are frequently to be seen small white dome like structures said to be potent for keeping away sickness. At some place on the roof there is a kind of stove with a chimney in which twigs of trees, green for preference, are burnt each morning as an offering to the spirits of the mountains. The dense smoke from the green twigs pouring out of the little chimney. The ordinary smoke from the kitchen finds its way out of the roof by one or more square openings which may or may not have a raised cover to keep out the rain.

A big Tibetan mastiff is generally on guard near the front door.

Day forty-four August 29th, 1923. Yang Cha to Chia Pieh - 12½ miles

They set off in good time this morning - just after 7 a.m. At first there was a somewhat steep zigzag up the hill side to about 15OO feet above the Mekong - then the road remained fairly level with a slight tendency to rise, until about 9.30 when we reached Chia Pieh Ya’kou the highest point (7,980 ft.) There was the usual heap of "mane" stones and a path leading off to the right to a lamasery away up in the hills.

Looking South along the Mekong towards Yang-cha

Looking South along the Mekong towards Yang-cha

Further along the gorge by the Mekong

Further along the gorge by the Mekong

“The view from the top back towards Yang 'Tsa was magnificent - a great valley with steep sides and the Mekong away down below. As we descended we saw Tibetan houses with their white walls and flat roofs glistening in the sun - a sharp ascent and an equally sharp descent brought us at 11 a.m. to Kuo Nia - another Tibetan village with its own rushing stream of clear water - making its way down to the Mekong.

Great gorge and rocks after leaving Kuo-nia (by the Mekong)

Great gorge and rocks after leaving Kuo-nia (by the Mekong)

“We rested for 2 hours and then the Tibetan boy and I went on ahead, to see what we could fix up in the way of a night's lodging. We had another climb over a small ridge, thereby cutting off a big loop of the River - where it wound round a conical mountain with a white beacon on the top. When we got down by the River again it passed through great cliffs of yellow sandstone - mostly bare of trees, and the river way below. We started once more to rise and went steadily up to a pass only about half a mile from this place. On the way up we had our first view of the great snow-covered mountain K’a K’a Pu”.

View of the K'a K'a Pu mountain range

View of the K'a K'a Pu mountain range

“Coming down the path we met a number of pilgrims and on enquiring found that they are making a pilgrimage round the mountains. It takes 14 days. All seem to be in their best clothes, although one man had his coat off, hanging round his waist. Another jovial old man was twirling his prayer wheel. I persuaded one group to stand while I took a snapshot. Each one was carrying a bamboo, mostly with a tuft of green tied on the top. One young man would not stop and rushed past me, but the others were very jolly about it and took it as a great joke. They said they were a group of about 40 all from one little district near the mountains and leaving one or two at home to look after the stuff, they were on this pilgrimage - men, women and children”.

Tibetan pilgrims near River Mekong, going around K'a K'a Pu mountain

Tibetan pilgrims near River Mekong, going around K'a K'a Pu mountain

Their path descended to the pretty little Tibetan village of Chia Pieh (7,234 ft.) a village of eight families, surrounded by steep bare hills, and with the Mekong just close to it and away down below.

“The Tibetan boy and I arrived at 3 and got things fixed up. Then about half an hour later the others began to arrive. GP arrived about 1 hour after them. He said that the mules had practically all given out and one had died. The Tibetan Muleteers said it was because the No.1 muleteer had died, (I thought the real reason was that since his death they had been underfeeding the animals, so as to pocket the money). One mule which was nearly finished was sold for $5.00. The rest struggled in and we will start afresh with new mules when we reached Atuntze”.

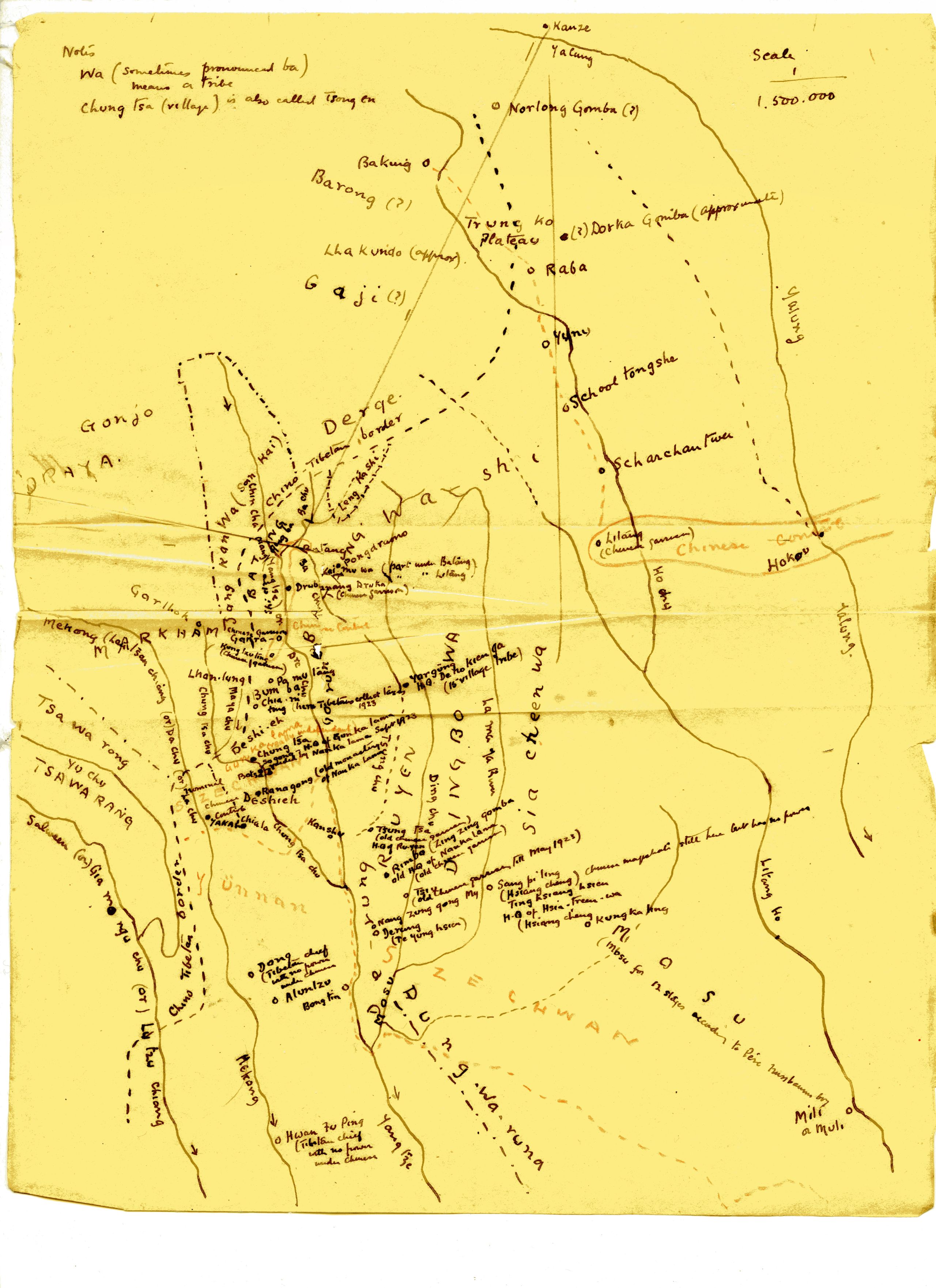

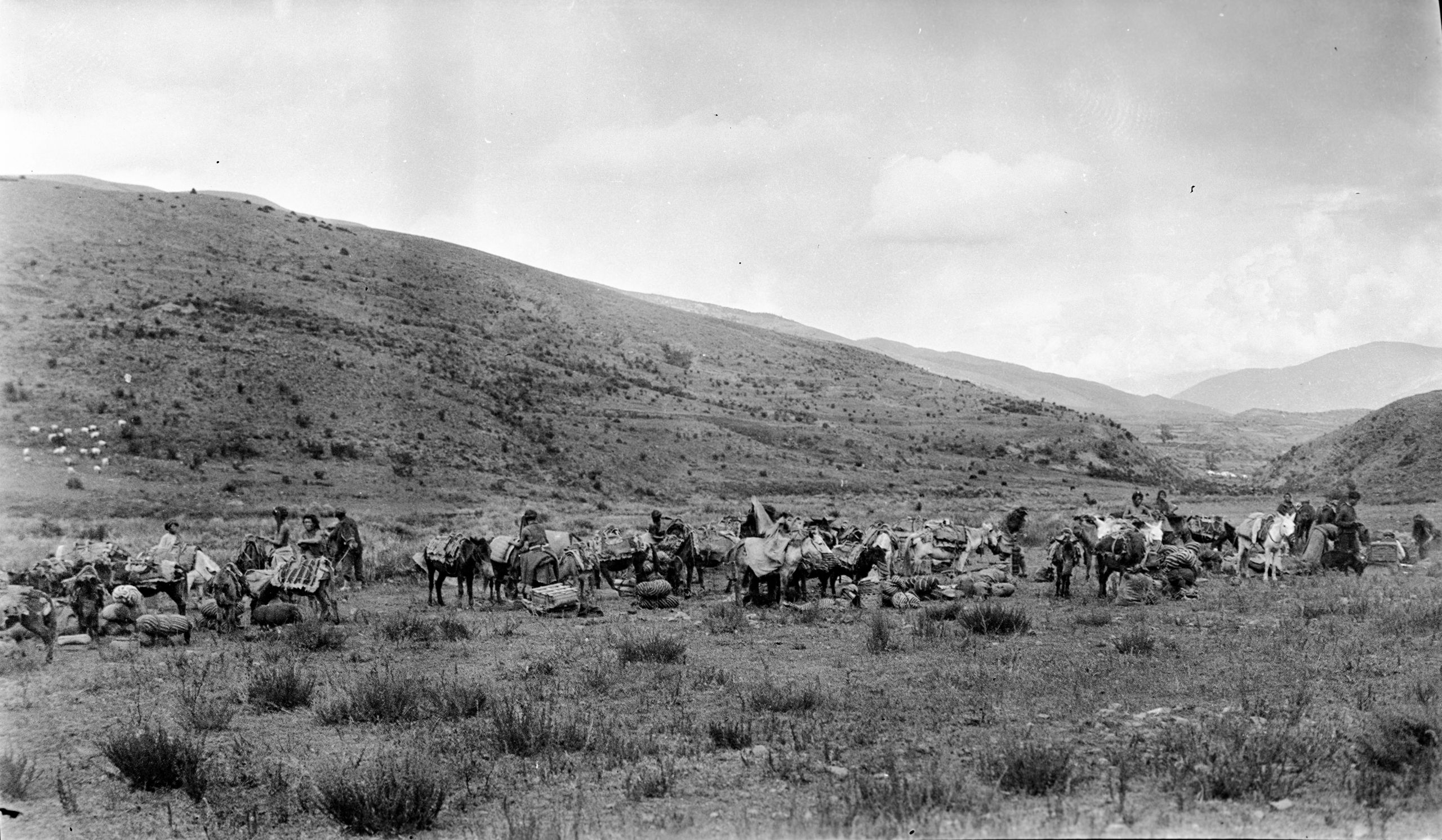

Day forty-five Aug; 30th 1923 Chia Pieh to Atuntze - 16 miles

They left Chia Pieh at 7.30 a.m. The first part of the road was down-hill to the Mekong (7,020 ft.) again, then along the left bank to the Mekong for three miles. The country now seemed to be different in character - great bare hills with no trees and only a little scrub scattered over them. After the 3 miles practically on the level they left the Mekong and entered a big valley (Yung-chu valley), down which a rushing stream made its way to the Mekong. Their path lay up this valley going NE. The stream came from Atuntze (known in Tibetan as Gyu), and it was a case of following it upstream till they got there.

Last view of road by Mekong before leaving for Atuntze

Last view of road by Mekong before leaving for Atuntze

“The mules were rather rocky again. At Kung Shui we had a two hours rest, and then at 1.15 p.m. I pushed on with the “youthful warrior”, and GP followed with the caravan. We continued to follow the small river till we came to a place where the valley gave a big bend to the right and then curved to the left. This brought us to the top part of this valley. There were numerous scattered houses before the little town of Atuntze (10300 ft.) came into sight. It was a steady climb all the way till we arrived at 4.15 p.m. We went to the house of Monsieur Peronne, a French musk merchant who had been there 20 years. He is exceedingly kind and had heard we were coming. He arranged for us to be put up at a house belonging to the R.C. Mission where Mons. & Madam Haeffuer had lived 2 years before”.

“GP arrived soon after us with the mules and we got fixed up. At 6.30 we went for dinner with M. Peronne. He has a Tibetan wife, a little girl about 9 years old, and a boy aged about 6”.

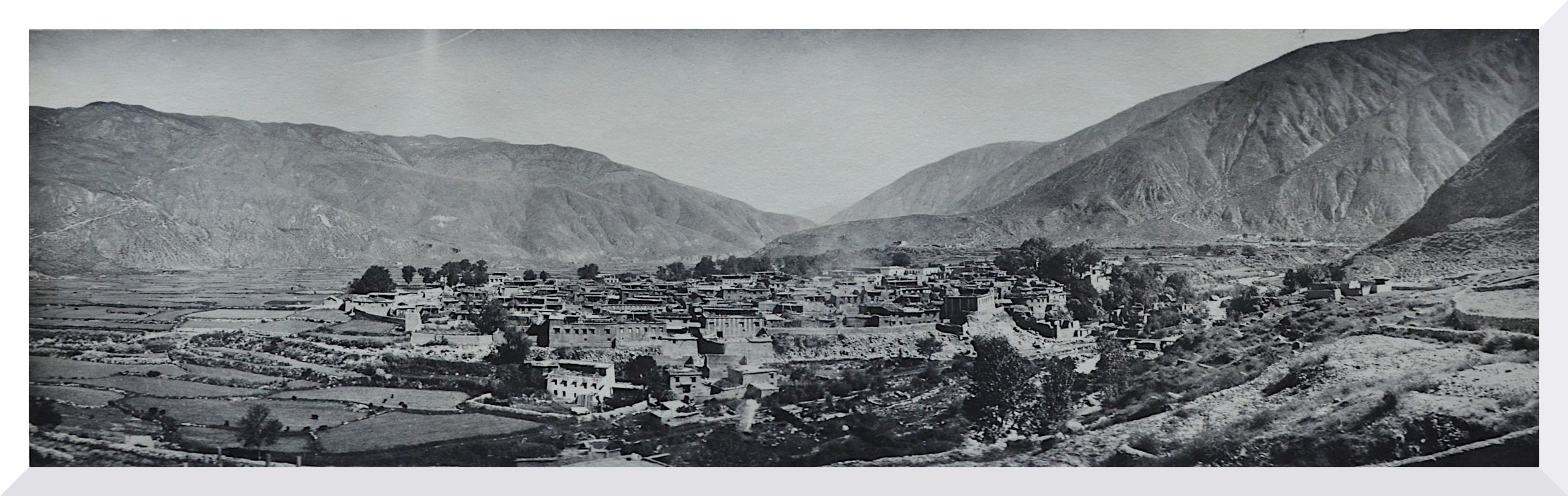

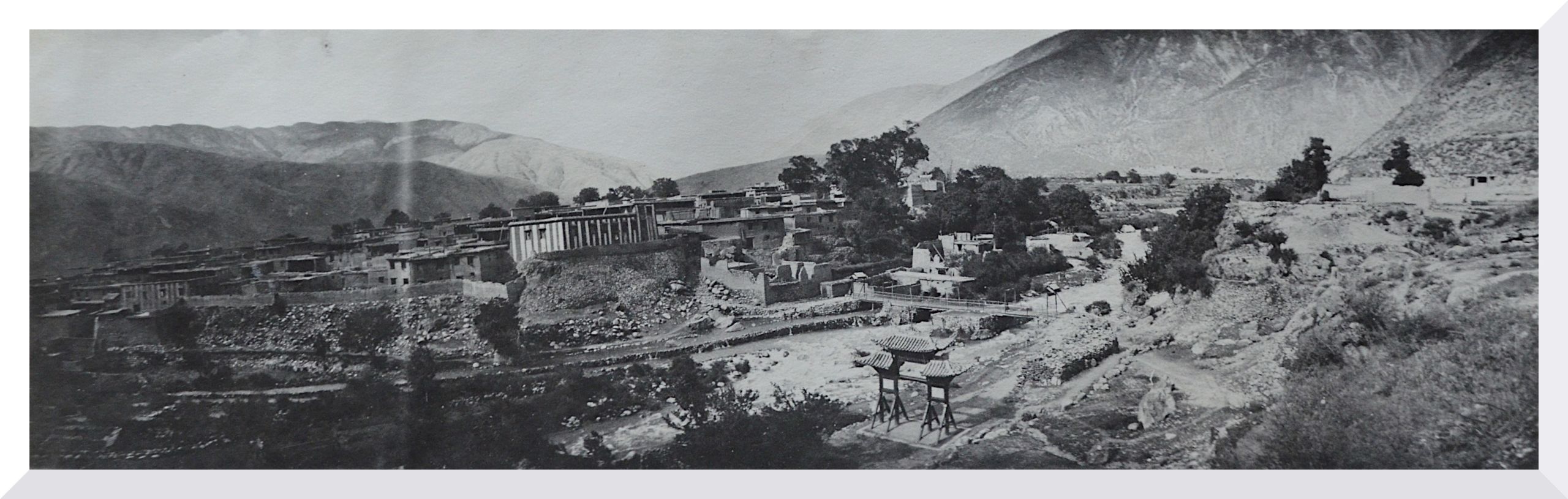

Atuntze was 631 miles from Yunnan-fu

At Atuntze 28th August 2023

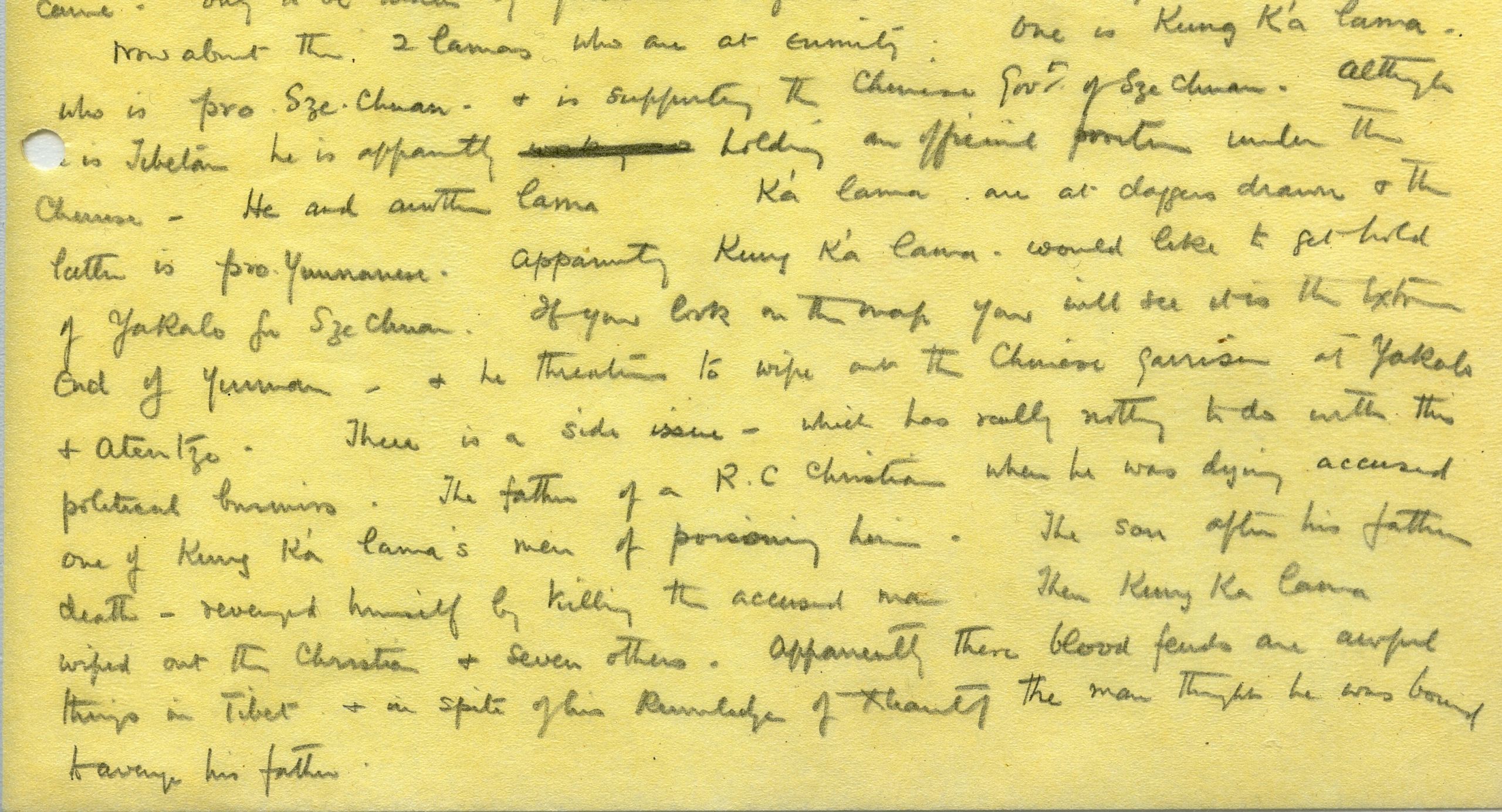

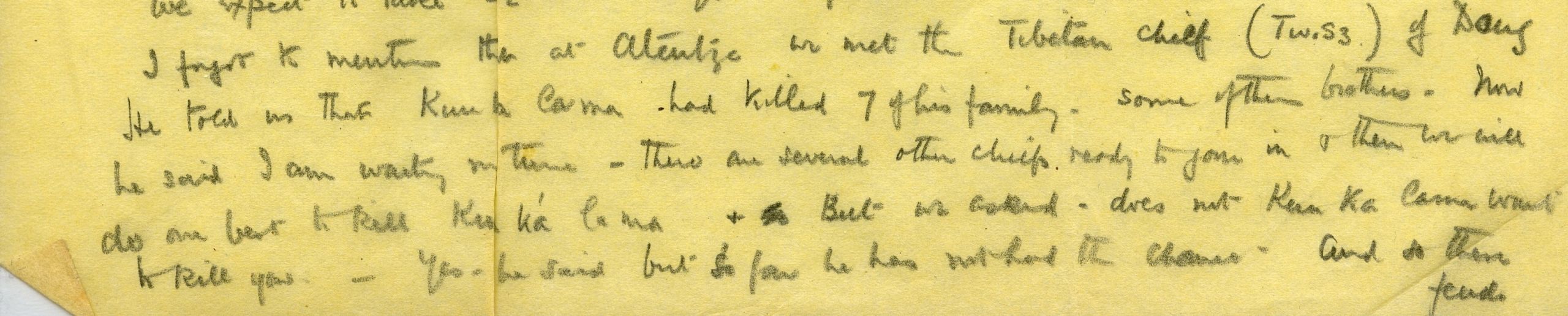

HGT made the following entries in his journal about the two warring lamas:

"Now about the two lamas who are at enmity. One is Kung K'a lama who is pro Szechuan, and is supporting the Chinese Government of Szechuan. Although he is Tibetan he is apparently holding an official position under the Chinese. He and another lama, Lan K'a lama are at daggers drawn and the latter is pro-Yunnanese. Apparently Kung K'a lama would like to get hold of Yakalo for Szechuan. If you look on the map you will see it is the extreme end of Yunan, and he threatens to wipe out the Chinese garrison at Yakalo and Atuntze".

"There is a side issue - which has really nothing to do with this political business. The father of a R.C. Christian, when he was dying, accused one of Kung K'a lama's men of poisoning him. The son after his father's death - revenged himself by killing the accused man".

"Then Kung K’a Lama wiped out the Christian and seven others. Apparently these blood feuds are awful things in Tibet and in spite of his knowledge of Xhantj the man thought he was bound to avenge his father".

"At Atuntze we met the Tibetan Chief (t’wiss) of Dong. He told them that the Kun Ka Lama had killed his father (the “son” above), and seven of his family - some of them brothers. “Now” he said, “I am waiting my time - there are several other chiefs ready to join in, and then we will do our best to kill Kun Ka Lama.” I asked, “does not Kun Ka Lama want to kill you?” - “Yes”, he said, “but so far he has not had the chance”. In spite of his knowledge of Xhantj the man thought he was bound to avenge his father".

"These Tibetan blood feuds go on, sometimes for hundreds of years, until one side is wiped out or both sides are exhausted".

"There is apparently no trouble between Atuntze and Yakalo, but between Yakalo and Batang we shall have to be careful.”

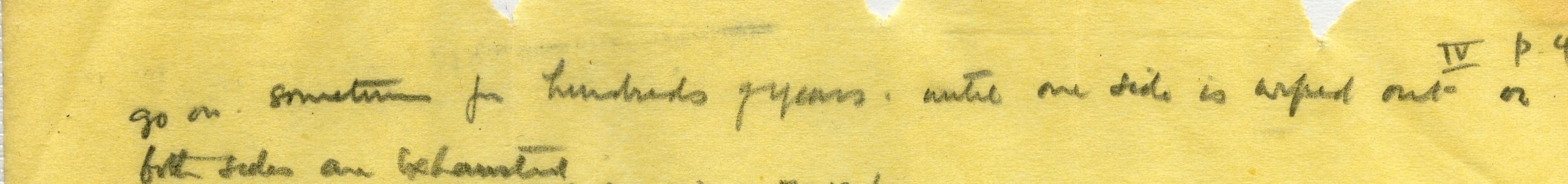

Sketch map of the route from Atuntze to Batang and on to Kanze

Sketch map of the route from Atuntze to Batang and on to Kanze

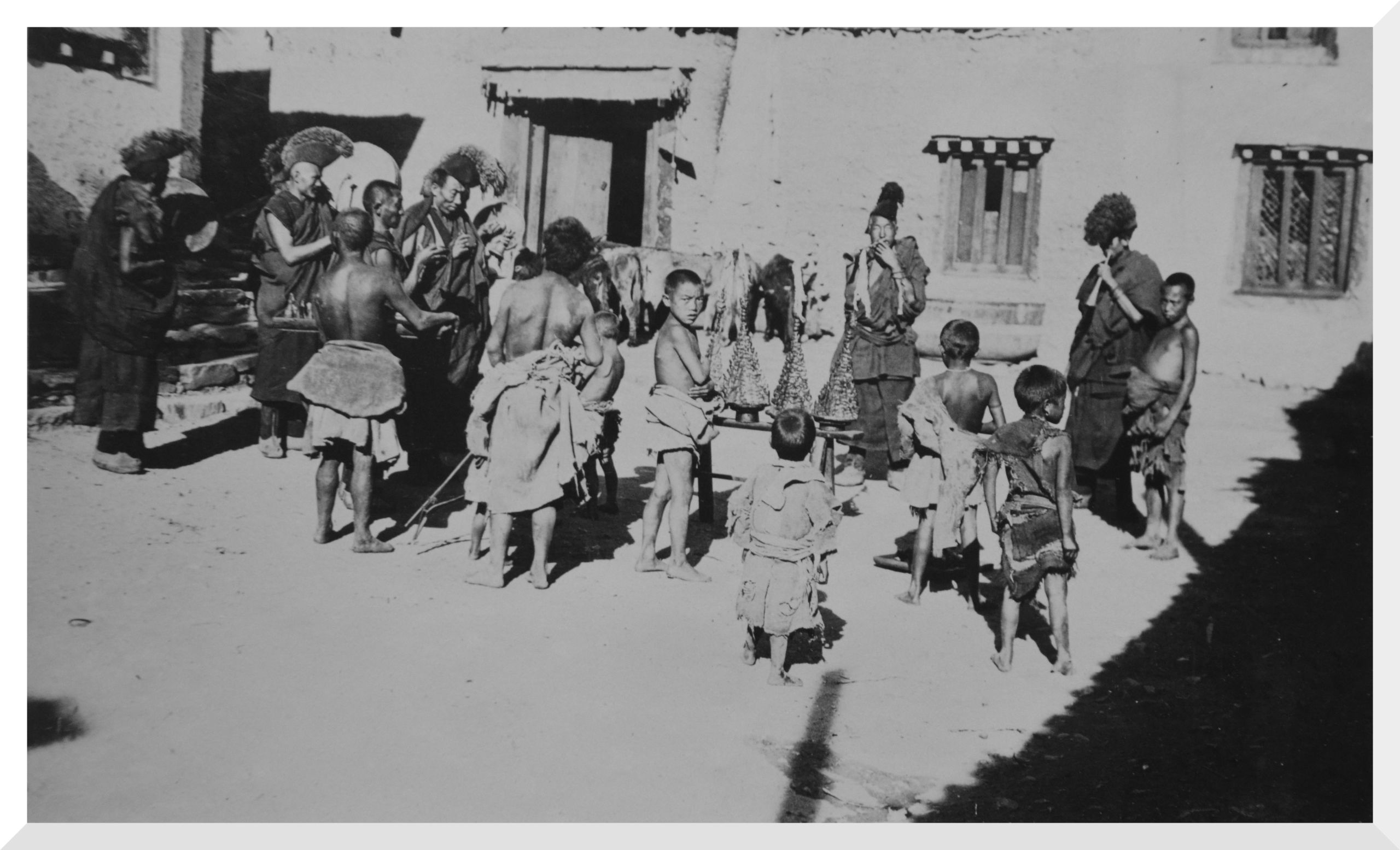

Days forty-six to fifty Sept 1st-5th 1923 Stayed in Atuntze

“Whilst there (at Atuntze) we got some more news about the squabble between the Kun K'a lama and the Lan Ka lama. It seems the latter crossed the Yangtze into Szechuan - a few months ago, invited some of the Szechuan soldiers to a feast, and then attacked them - killed 4 and bolted with 300 rifles, a lot of ammunition and a small gun. The former, the Kun Ka lama had also wanted the Szechuan soldiers to help him to attack Atuntze. They refused, there was a squabble. He attacked them and they retaliated and nearly killed him, but they could not fire straight. He got away with his men and is now somewhere in this country - waiting till he is strong enough to make another move”.

The Tibetans in this district, where they formed the majority of the population, seemed to prefer to be under Chinese rule. M. Peronne said the lamas were constantly fighting among themselves, and there was a vendetta between the chiefs, whilst the Chinese did keep some sort of order and peace. In Atuntze, they met the local Tibetan chief (called Twiss) from Dong, their next stop.

They learnt the Mekong and Yangtze in these parts do not freeze, though there is sometimes an ice fringe on the banks of the Mekong. They planned to stay at Atuntze for 2 full days and then start on again for Yakalo on the third day.

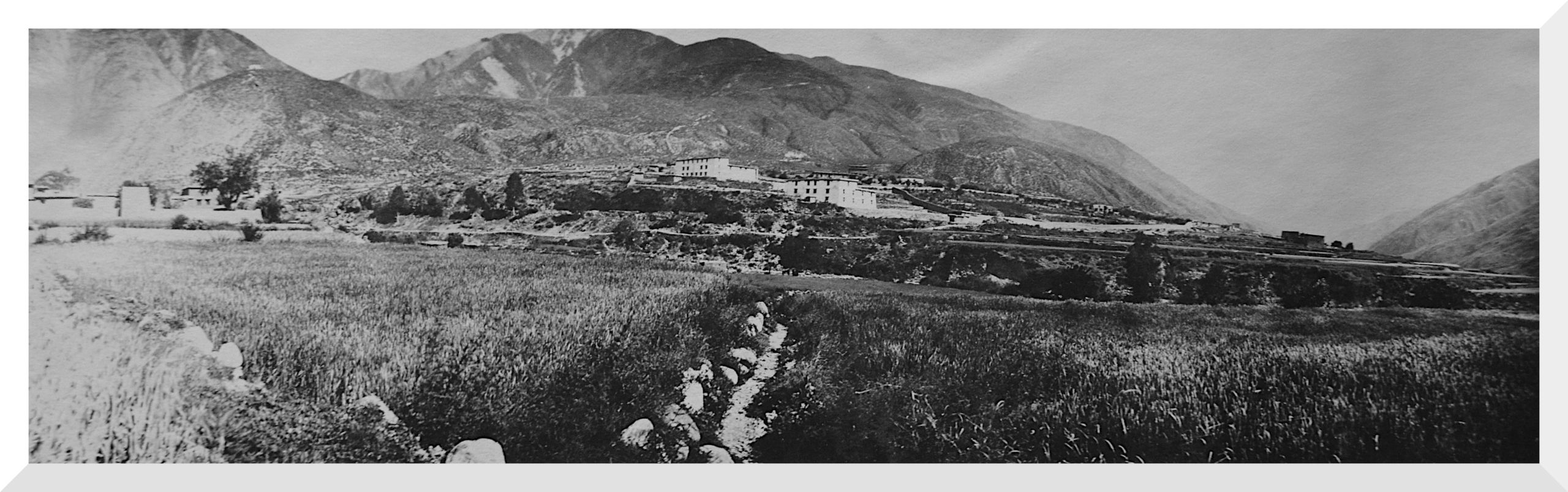

“A-tun-tze is a town of four hundred families, half Chinese and half Tibetan, at an elevation of 10,810 feet. The country is nominally under Tibetan princes to whom the Chinese have granted the rank of t'u-ssu, but they have no power. The northern prince rules the country from Yakalo to Dong, the next stage north. The southern prince rules some way south down the Mekong. A third t'u-ssu is a Mosu who resides at Yeh-chih".

"Trade is very bad. The Chinese are gambling and letting things go. Chinese rupees are current here. Among the rupees I found one of the East India Company of William IV. 1835. There is a bad habit here of cutting the rupees in half, and often people will not take what they considered the smaller half!”.

Day fifty-one September 5th Atuntze to Dong - 9 miles

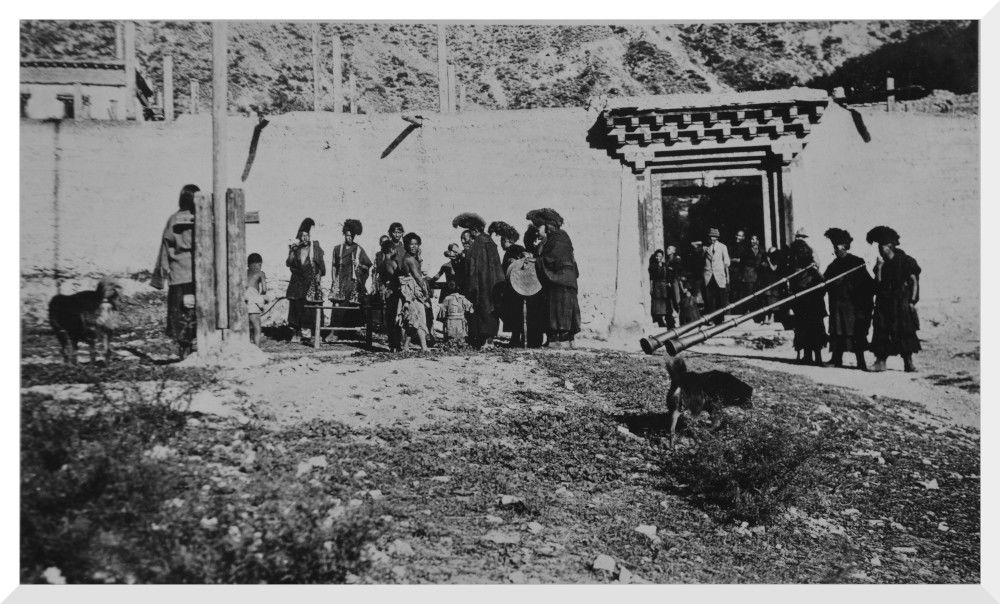

“We left Atuntze just after 2 p.m., having hired fresh mules and after I had recovered from an attack of fever, and set out again on our march to Yakalo (in 4½ days) and then on to Batang. Monsieur Peronne accompanied us to the end of the little town, then the general went on, while I waited to see to the mules and get a parting snapshot of Atuntze”.

Leaving Atuntze & saying farewell to M. Peronne

Leaving Atuntze & saying farewell to M. Peronne

“M. Peronne is very keen on stereoscopic photography. He has taken two snaps of GP and myself - and has promised to send us copies. They are intended for use with a magnifying stereoscope. He also has some beautiful negatives of the district. He has just got out a hundred ,and 20 dozen plates; to last him, he says the next two years, after which is going back to France. He speaks English quite well, and was most kind. We went to him to lunch each day and he came to us for dinner".

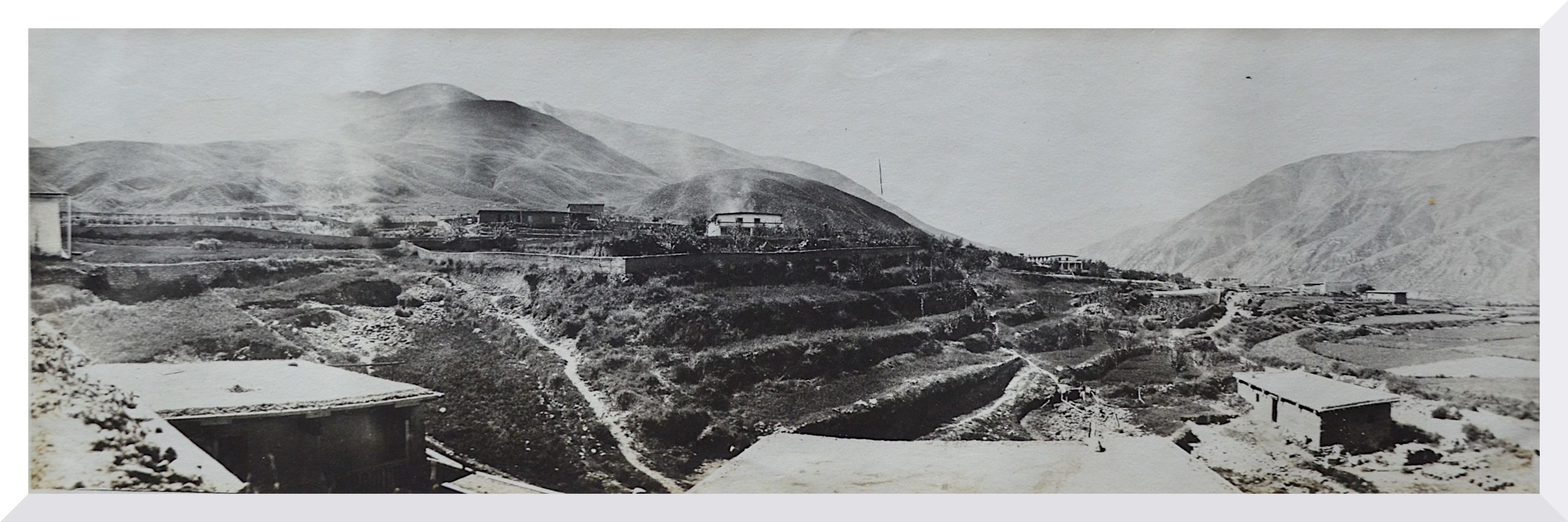

“The first part of today’s journey - a steep climb for two and half miles - was uphill to the Chu la pass (11480 ft.). Then downhill all the way for six and a half miles to the village of Dong (8216 ft.) It is a Tibetan village of forty families situated deep down in a valley”.

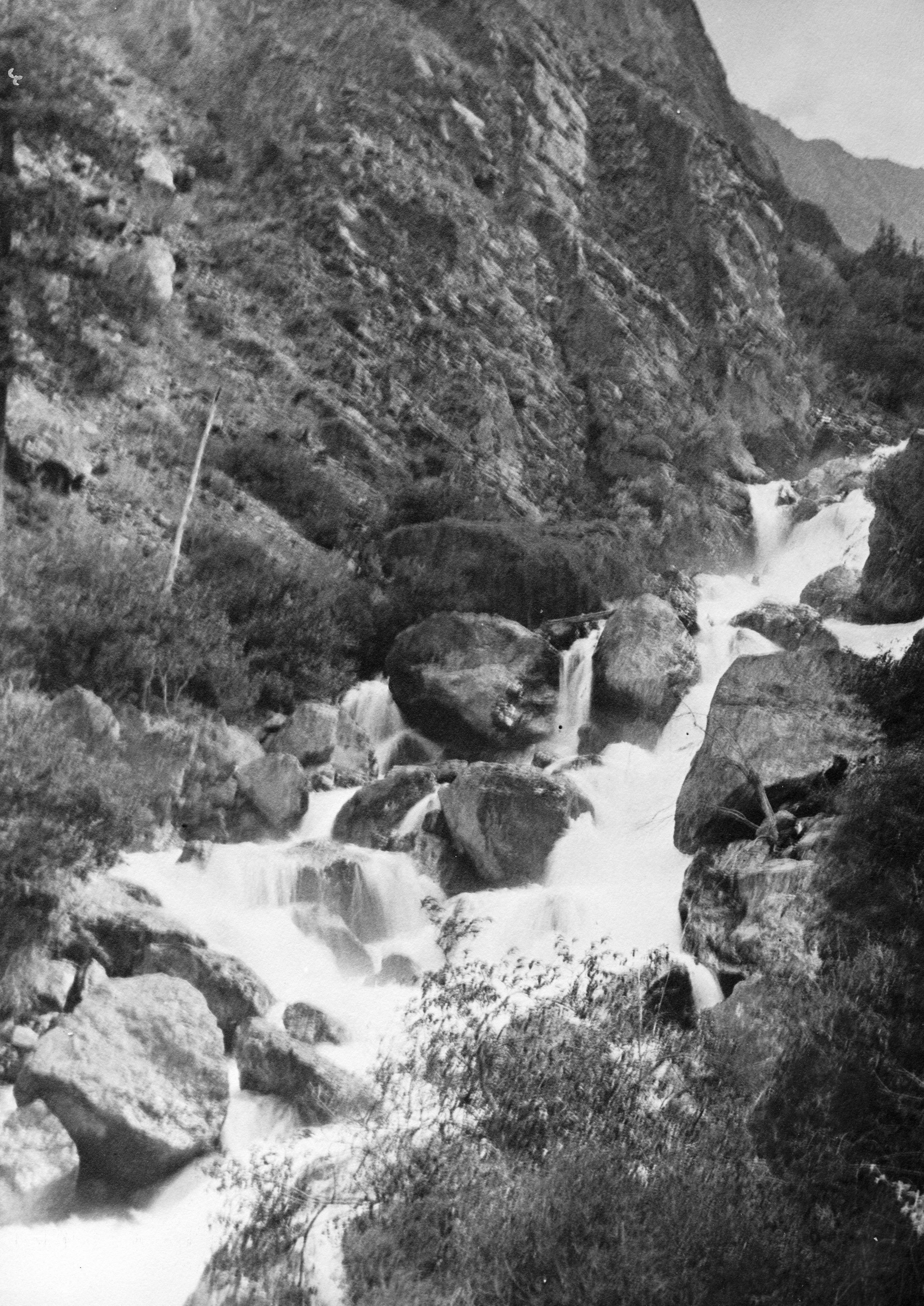

Waterfall at Dong

Waterfall at Dong

“The downhill part of the journey was very beautiful, following a small stream, which every now and again broke into small cascades and waterfalls. About halfway down, a huge vertical rock - about 500 ft. high, - stood out in the defile on the right-hand side, like some great sentinel guarding the way.

“Looking back, the great mountain of light sandstone, with firs, growing from the crevices of the rock looked like a beautiful Xmas tree - shining in the sunlight of the setting sun, while we were down in the shadows”.

Day fifty-two September 6th 1923. Dong to Ku Shih (or Go-hsieh) - 19¼ miles

They left Dong at 7:30 a.m. and at 9:15, after following the small river from Dong down, they arrived at the Mekong again. It was of a dark reddish colour, showing that it had been raining lately in Tibet. They then followed the Mekong and arrived at Ku Shi at 12:30, after travelling 13½ miles. From this point on they planned to only travel in short stages – days’ walk.

“On route we met a man from Ba-Tang. He reassures us that the road from Yakalo to Ba-Tang is quite quiet”.

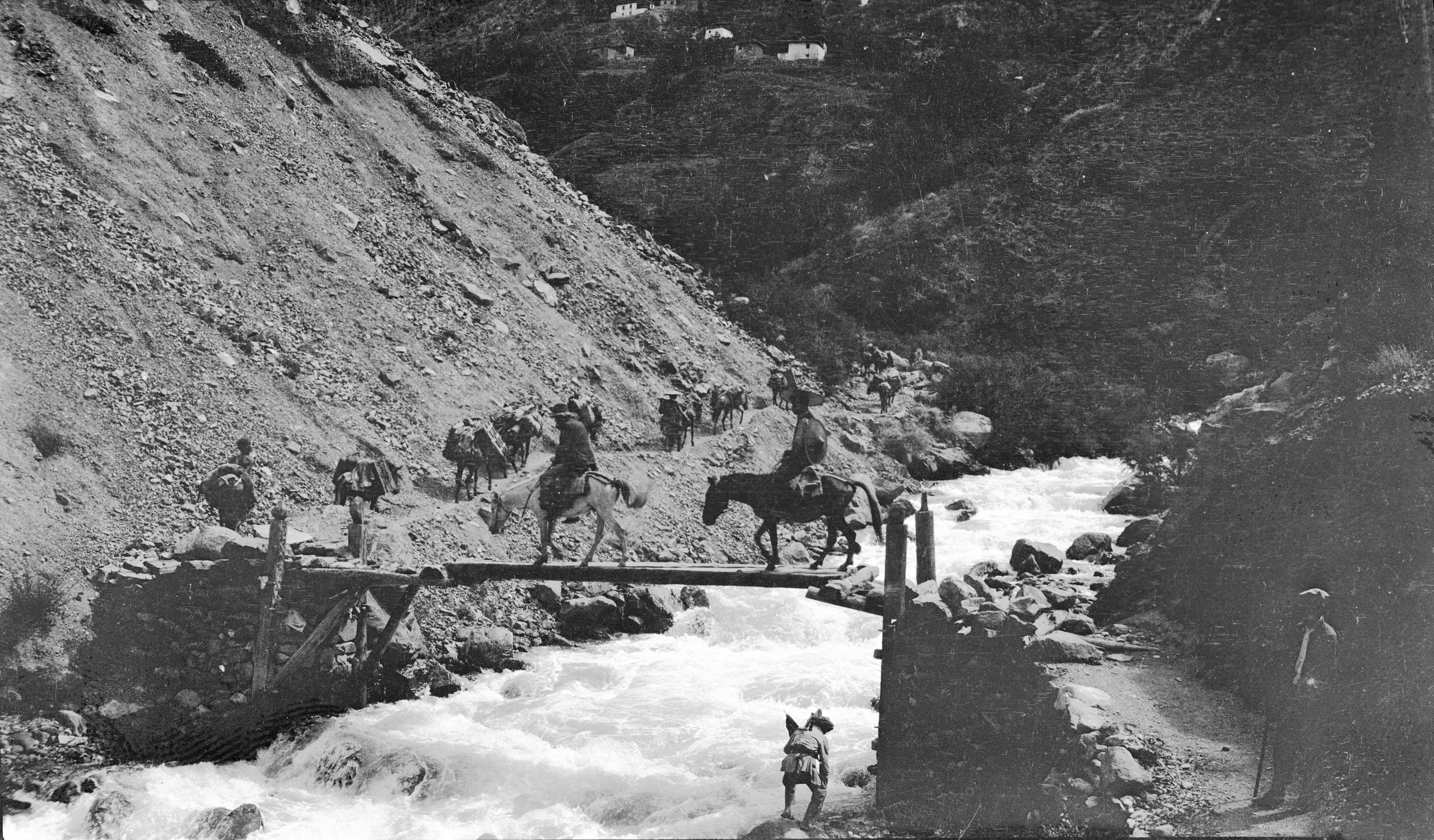

The Ru-wa-shou Gorge between Dong and the R Mekong - GP riding

The Ru-wa-shou Gorge between Dong and the R Mekong - GP riding

There was a rather steep descent down the Dong-lung Chu valley. The path lead through the wild Ru-wa-shou gorge between high rocky precipices - great walls of rock, rising almost vertically, of red and yellow sandstone. High up on a ledge was a monastery.

Then there was a climb of 500 feet to the Ma-pa La, (7,890 ft.), from which there was a steep descent. GP recorded in his journal:

- “On the opposite side was Ma-pa-t'ing, from which there is a trail between A-tun-tzu and Chamdo. After two stages this trail leaves the river, crosses the wild Shu La and proceeds on to Pi-t'ou monastery, which has always been notorious for its anti-foreign feeling, and which pays little attention to the Kalon Lama at Chamdo”.

HGT noted in his journal and letter home:

“We stayed in a house in Ku-Shih – on the inside veranda. In one corner was an old lady who was blind – she spent her time, sitting on the floor – tailor fashion, counting beads and turning a small prayer wheel. The landlady admired my carpet slippers!”

“There is quite a strong breeze blowing from the south, and it looks like rain. I must stop”.

Day fifty-three September 7th 1923 Ku-Shih to Sung-Shih - 19½ miles

“We left Ku Shih at 7 a.m. and for the first hour had a stiff climb (1,600 ft.) up the hill – till we reached the topmost point, Ku-La (8,655 ft.) At this spot was a small white square erection, which at home would be called a cairn – but here is called a “luan shi”. There are frequently stones carved with the characters “om mane padme hum,” placed there when for example a child is sick. But this one had no special significance except to mark the highest point”.

After reaching that height, they skirted round the mountains, passing through Jung, a scattered village of about sixty-five houses. All the while they kept parallel to the Mekong – which was about 2,000 ft below. They reached their midday halt at 11:30 – a place called Tang Ku Kung (or Tang Ku Gung). They could see the road stretching far ahead – over a big round spur of mountain, and then over a sharp knife-edge ridge – away in the background was a five peaked mountain.

They lunched under the shade of a big Walnut tree and looking across the Mekong could again see the great snow-capped Ka' Ka Puh mountain (or Ka-go bo mountain) said to be 20,000ft (though the map they were using said 16,000 ft).

“As we face the mountain, – just to the left, on the other side of the river was a great valley, – up which we could see a path running, which we were told was the main road up to the Shu-la (Shu pass) across which practically all the traffic between Yunnan-fu and Tibet (Lhasa) passes”.

Bridge over torrent by a landslide near Sung shih

Bridge over torrent by a landslide near Sung shih

After lunch they started again at 1:15 and keeping at a high level, crossed the rounded, and then the sharp knife edge spur of the mountain. There was a steep descent to a gully, then a slight rise to Sung-ting at 17 ¾ miles, and down to cross a torrent near a landslide, followed by a short rise to Sung-shih.

“Since leaving Atuntze, we have in the caravan, a merchant who had asked permission to join us, and also a woman with a child. The woman was from Batang and was making her way back".

“The woman’s story is that she, her husband and child whilst on their way down to Wei Si had all their belongings stolen by Tufei (bandits). The husband who was on his way to Kwang Tung – had gone on and left the woman to make her way back to Batang with the child (about 3 years old). A round faced cheerful little woman, – she is carrying the little one on her back. As she looked so tired (as I was walking) I told her she could ride my mule, or put the little one on it. She gladly accepted the offer for the child, so the wee mite was put on the saddle and then tied on with the woman’s girdle and the mother walked alongside. She would not ride herself, but it was a great relief to her, and mother and child chatted together as they travelled. On arrival at Sung Shih, GP and I talked things over, and agreed to pay for someone to carry the child the following day. We also gave her $1.00 to help her with food, for she had nothing except what had been given her, and our two “boys” were seeing that she had some of their food".

They had hoped to reach Napu, but stopped at Sung-Shih (7,126 ft.), 3 miles short, as they had had a long day – a distance of 19½ miles.

HGT wrote in his journal and letter home:

“I could not help thinking of my dear little Greta and her dear mother, and “fellow feeling makes us wondrous kind”.

“Alas, and alack! – My little green teapot went smash yesterday, and one of the Worcester cups. The teapot had lost its lid – near to Wei Si, and now the teapot spout has gone, right down at the base – so after nine years’ service, it is done for. However, the “boy” still manages to make tea in an enamelled cup. I hope to raise another teapot at Batang. (I must stop).”

Day fifty-four September 8th 1923 Sung-Shih to Pa-mei - 15 miles

They left Sung Shih at 7:30 a.m., and an hour later passed through Napu.

This was the place they had hoped to reach the previous day.

Na-pu houses built against rocks in the Mekong valley

Na-pu houses built against rocks in the Mekong valley

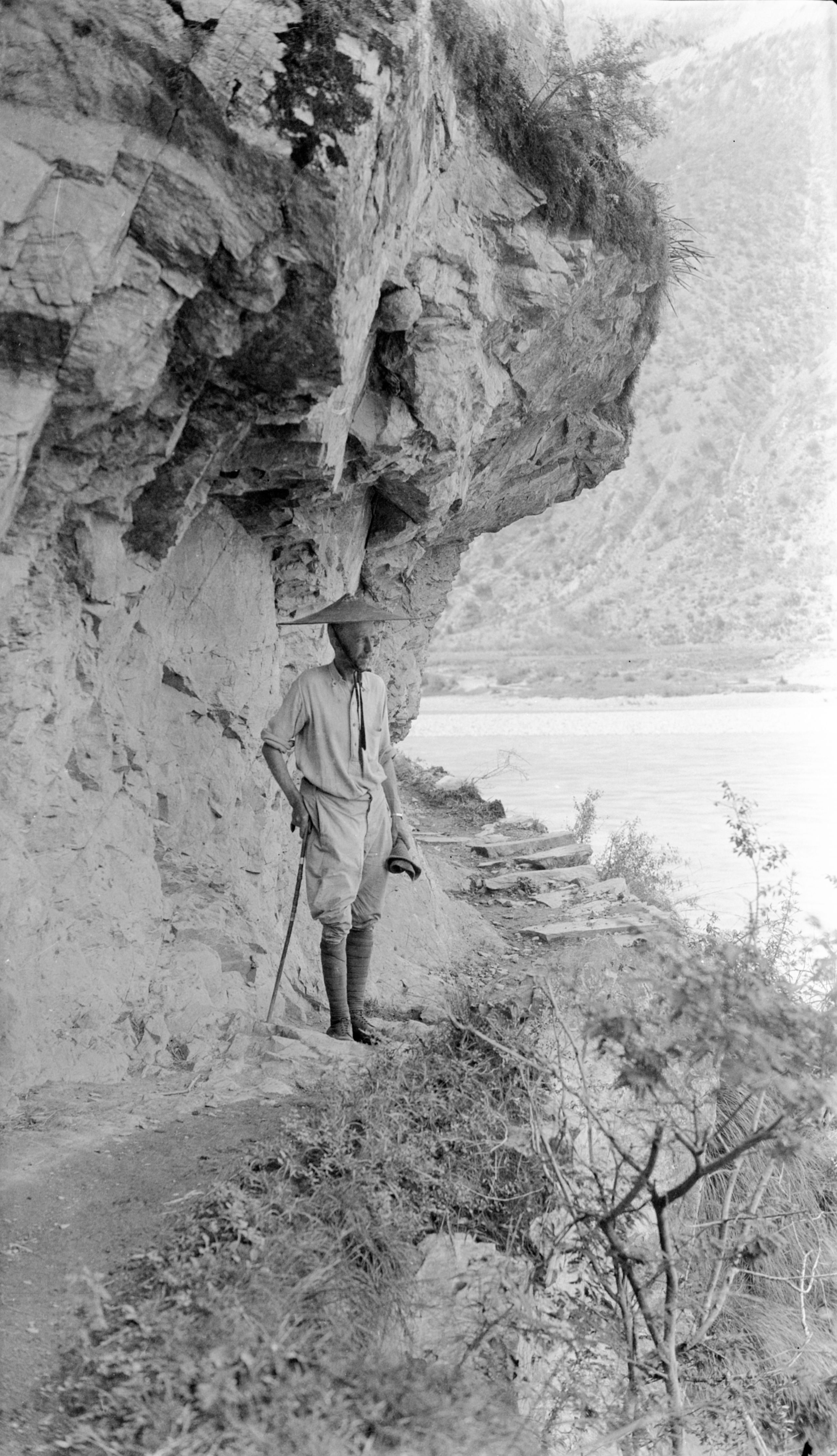

They continued along the left bank of the Mekong – in its various bends and turns. At one place, close to Chao Ba, the river gave a great bend, with its concavity to the West, and here the road which had previously been slowly rising above the river – dropped down to river level. At one place there were pieces of scaffolding to support planks for a roadway against the rocks.

HGT noted:

“I’ve never seen such a variety or colour of rock – these form the cliffs running down to the river. There was red sandstone and a blueish slate – a golden yellow formed by quartz – a beautiful purple, where the little streams had made watercourses, – and then away up and above, perhaps 2000 ft. up the deep green pine trees and down near the river, the bright green of the cultivated fields of an occasional village. It was marvellous – for at the foot of the cliffs was the river Mekong – an absolute chocolate brown – due to the rains in Tibet”.

“At one place looking up a great valley we could see towering above in the background, the snow-clad heights of the mountains which continue the Ka Ka Pu, and form the Mekong Salween divide. The pure white snow was glistening in the sun. Oh! for the brush of a ready painter! It was no use photographing it for the photographs would not show the colours”.

The road carried on scaffolding along the Mekong cliffs

The road carried on scaffolding along the Mekong cliffs

After descending to river level, the road mounted again to about 500 ft. above the river, and edged along the face of the rock, being carried on crude scaffolding. This was just about 9 miles from our starting place, one could look down from these rough planks, almost vertically to the river below.

HGT wrote:

“It was very strange for I had just mounted my pony after walking the first three hours, and was busy eating walnuts and getting the kernels out with a penknife, when the old soldier (a Tibetan with an antiquated gun), who is leading the way, called out to me, and looking up I saw this marvellous piece of scaffolding. I was soon off the pony and taking a photograph”.

Once again, the road descended to the River’s edge and then 3 miles from here, began to rise and zigzagged up to reach the village of Pa-mei (8,381 ft.) which was hidden in a small fertile fold high up on the hill-side - a village of twenty-five families.

Day fifty-five September 9th 1923 Pai meh to Peh Yung Gung - 15¼ miles

Heights: Ascent to Ta Key No 9,867 ft.

Drop to Shi-ti Chw Ka (lunch place) 8,490 ft.

Ascent to Mu Chia Kung 10,199 ft.

Slight descent to Peh Yung Kung 10,088 ft.

N.B. Gung (or Kung) = A Monastery; short for Gomba