Travelling the Tibetan and Mongolian Borders in 1923 - Part 3 Sichuan

Final journey of a remarkable traveller and companion.

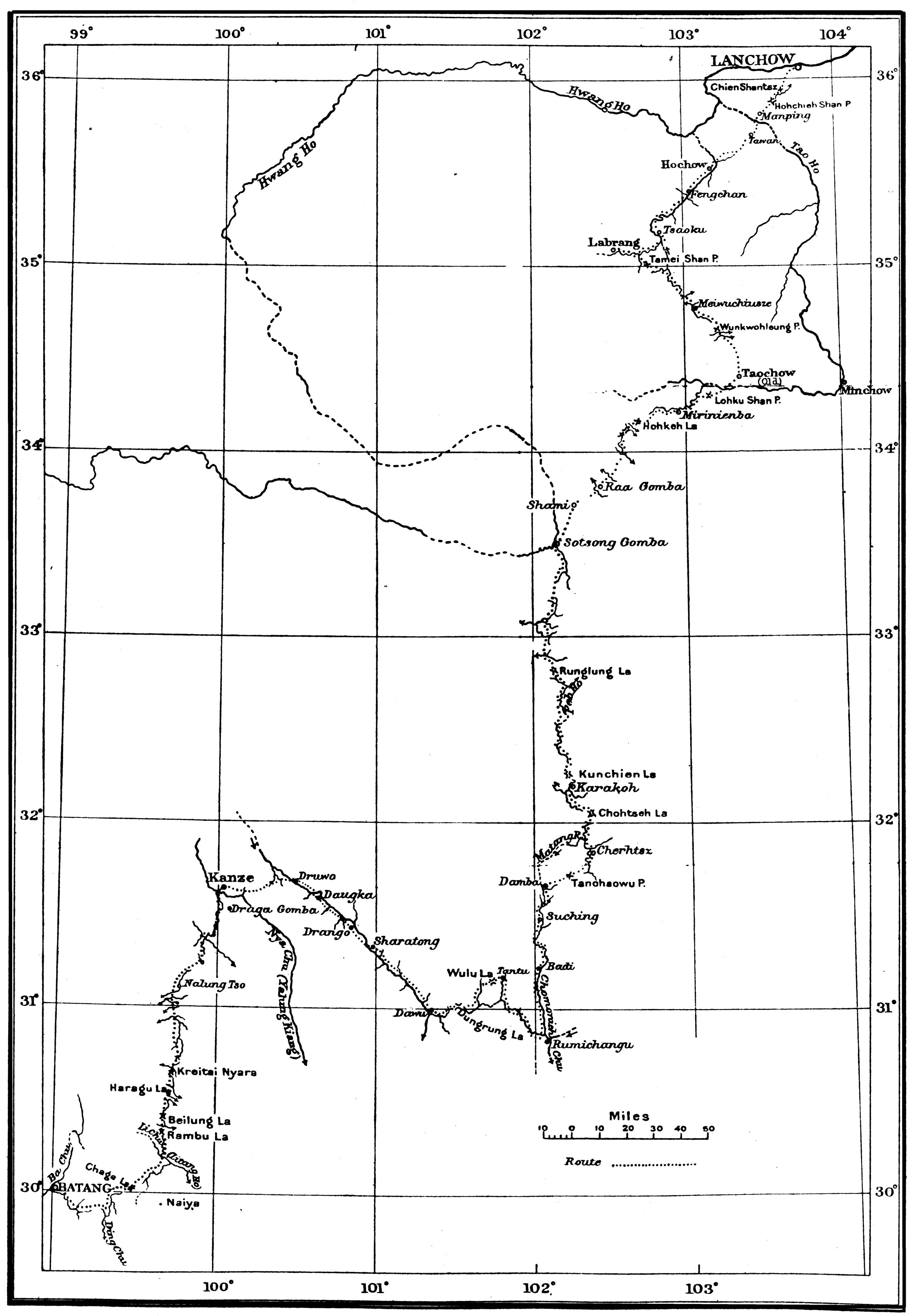

Overall hand-drawn map by HGT of the route from Batang to Lanchow Note: -The longitude of the great bend of the Hwang Ho (also known as the Yellow River) is from the observations of Capt. de Fleuselle on the expedition of Major D'Ollone (Geo. Journ. 36, 357, September 1910).

Overall hand-drawn map by HGT of the route from Batang to Lanchow Note: -The longitude of the great bend of the Hwang Ho (also known as the Yellow River) is from the observations of Capt. de Fleuselle on the expedition of Major D'Ollone (Geo. Journ. 36, 357, September 1910).

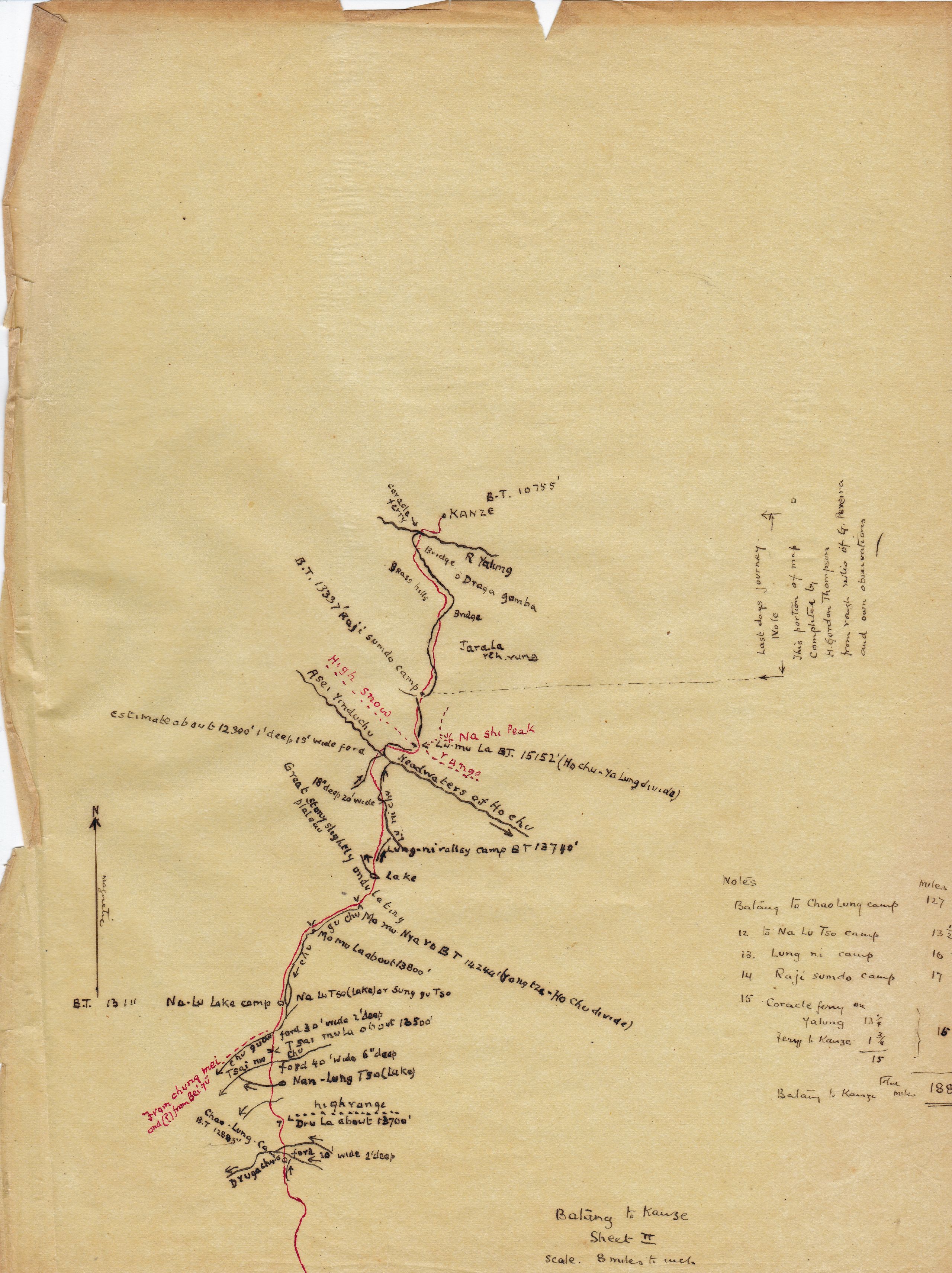

Click on the map above to see the route of the third section of the journey from Batang to Kanze (now known as Garze), - fourteen stages

Click on the map above to see the route of the third section of the journey from Batang to Kanze (now known as Garze), - fourteen stages

This shows the route from Batang to Ganze on a modern map. It is hard to be precise on the map as many of the place names have changed or are unlisted

This shows the route from Batang to Ganze on a modern map. It is hard to be precise on the map as many of the place names have changed or are unlisted

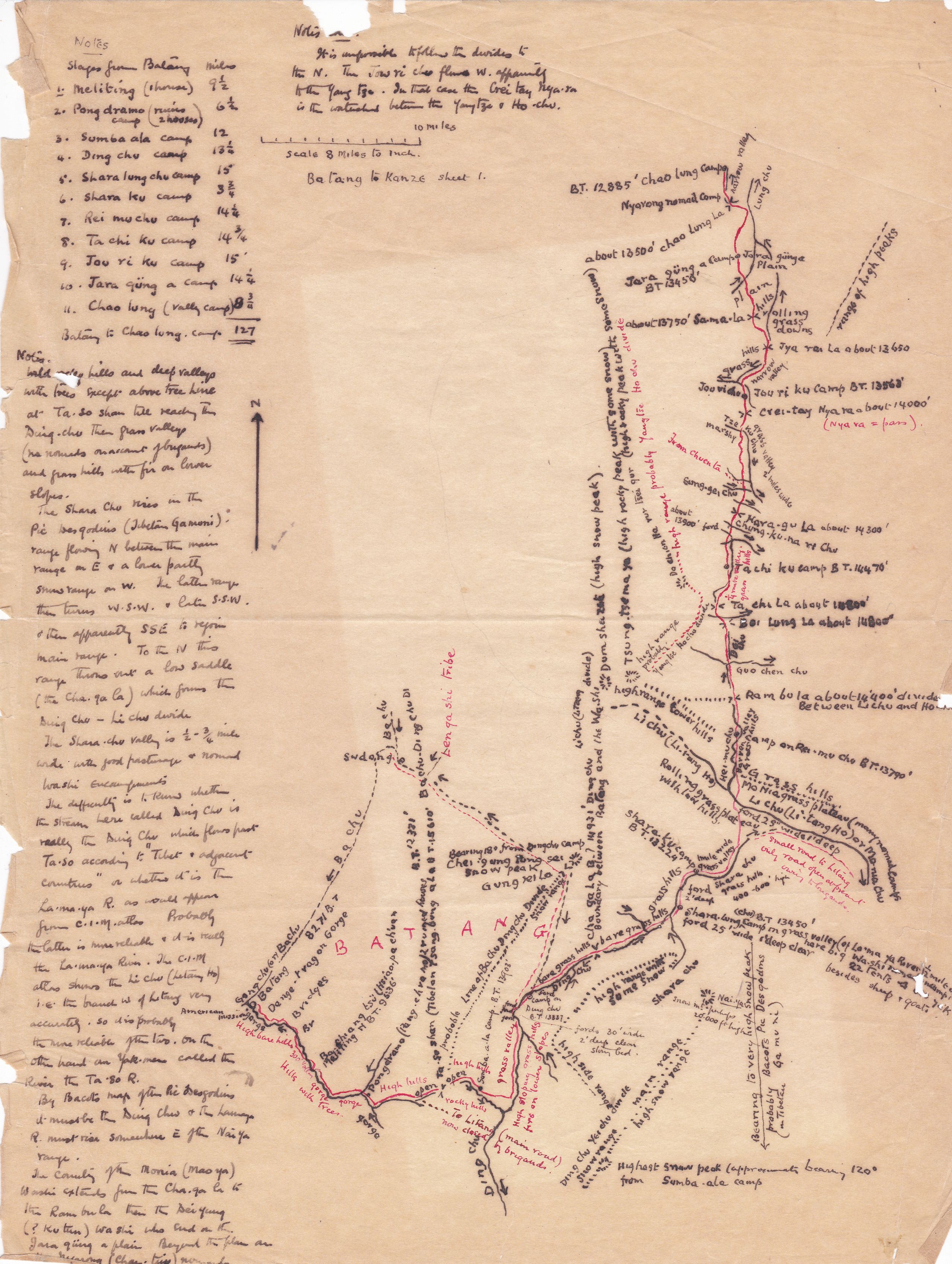

Hand-drawn sketchmap of the 1st stage - frrom Batang to Chao Lung camp in total a distance of 127 miles

Hand-drawn sketchmap of the 1st stage - frrom Batang to Chao Lung camp in total a distance of 127 miles

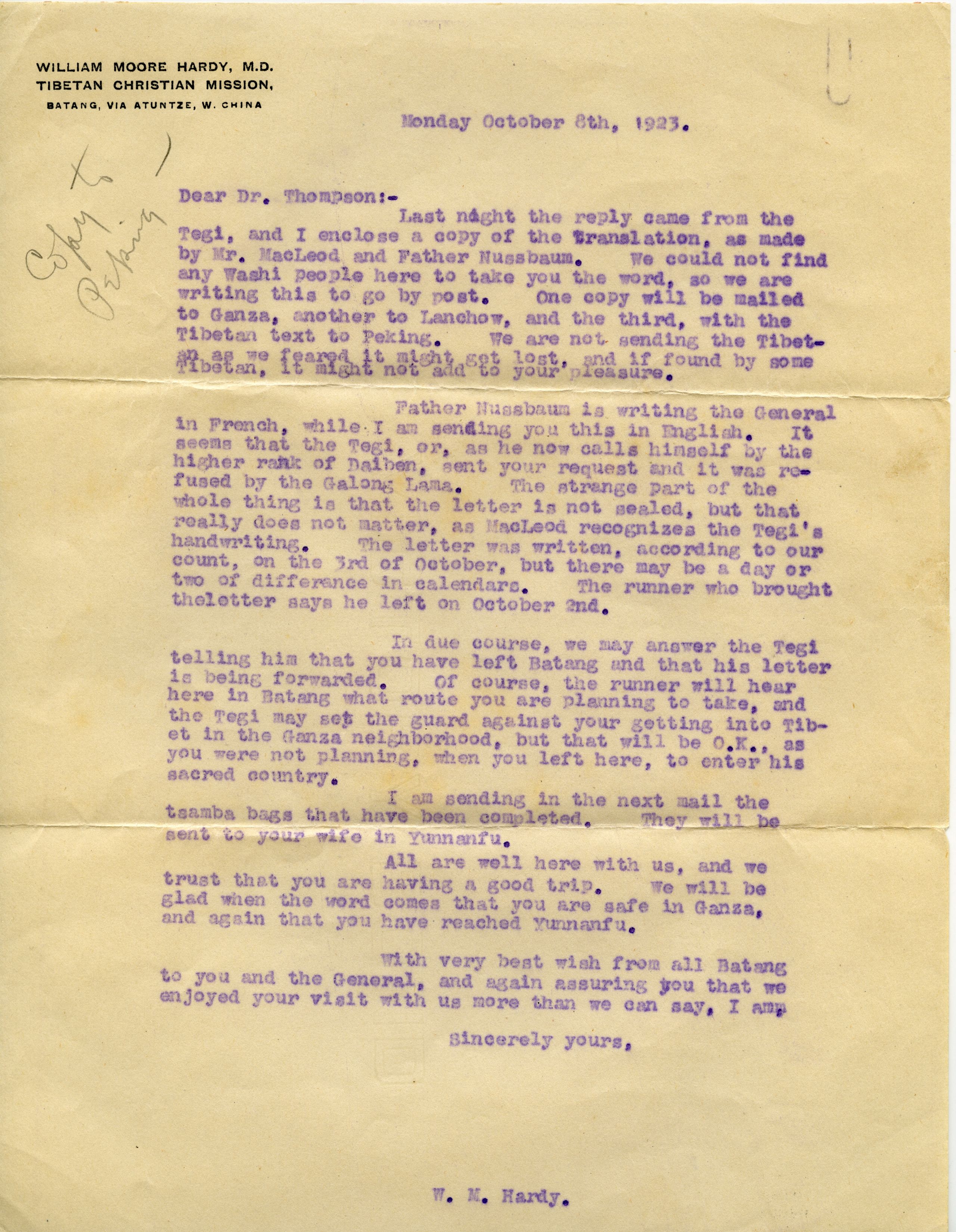

WILLIAM MOORE HARDY, M.D.

TIBETAN CHRISTIAN MISSION,

BATANG, VIA ATUNTZE, W. CHINA

Monday October 8th 1923

Dear Dr. Thompson

Last night the reply came from the Tegi, and I enclose a copy of the translation, as made by Mr. MacLeod arid Father Nussbaum. We could not find any Washi people here to take you the word, so we are writing this to go by post. One copy will be mailed to Ganza, another to Lanchow, and the third, with the Tibetan text to Peking. We are not sending the Tibetan, as we feared.it might get lost, and if found by some Tibetan, it might not add to your pleasure.

Father Nussbaum is writing the General in French, whilst I am sending you this in English. It seems that the Tegi, or, as he now calls himself by the higher rank of Daiben, sent your request and it was refused by the Galong Lama. The strange part of the whole thing is that the letter is not sealed, but that really does not matter, as MacLeod recognizes the Tegi's handwriting. The letter was written, according to our count, on the 3rd of October, but there may be a day or two of difference in calendars. The runner who brought the letter says he left on October 2nd.

In due course we may answer the Tegi, telling him that you have left Batang and that his letter is being forwarded. Of course, the runner will hear here in Batang what route you are planning to take, and the Tegi may set the guard against your getting into Tibet in the Ganza neighbourhood, but that will be O.K., as you were not planning, when you left here, to enter his sacred country.

I am sending in the next mail the tsamba bags that have been completed. They will be sent to your wife in Yunnan Fu.

All are well here with us, and we trust that you are having a good trip. we will be glad when the word comes that you are -safe in Gansa, and again that you have reached Yunnan Fu.

With very best wish from all Batang to you and. the General, and again assuring you that we all enjoyed your visit with us more than we can say. I am

Sincerely yours

W.M Hardy

WILLIAM MOORE HARDY, M.D.

TIBETAN CHRISTIAN MISSION,

BATANG, VIA ATUNTZE, W. CHINA

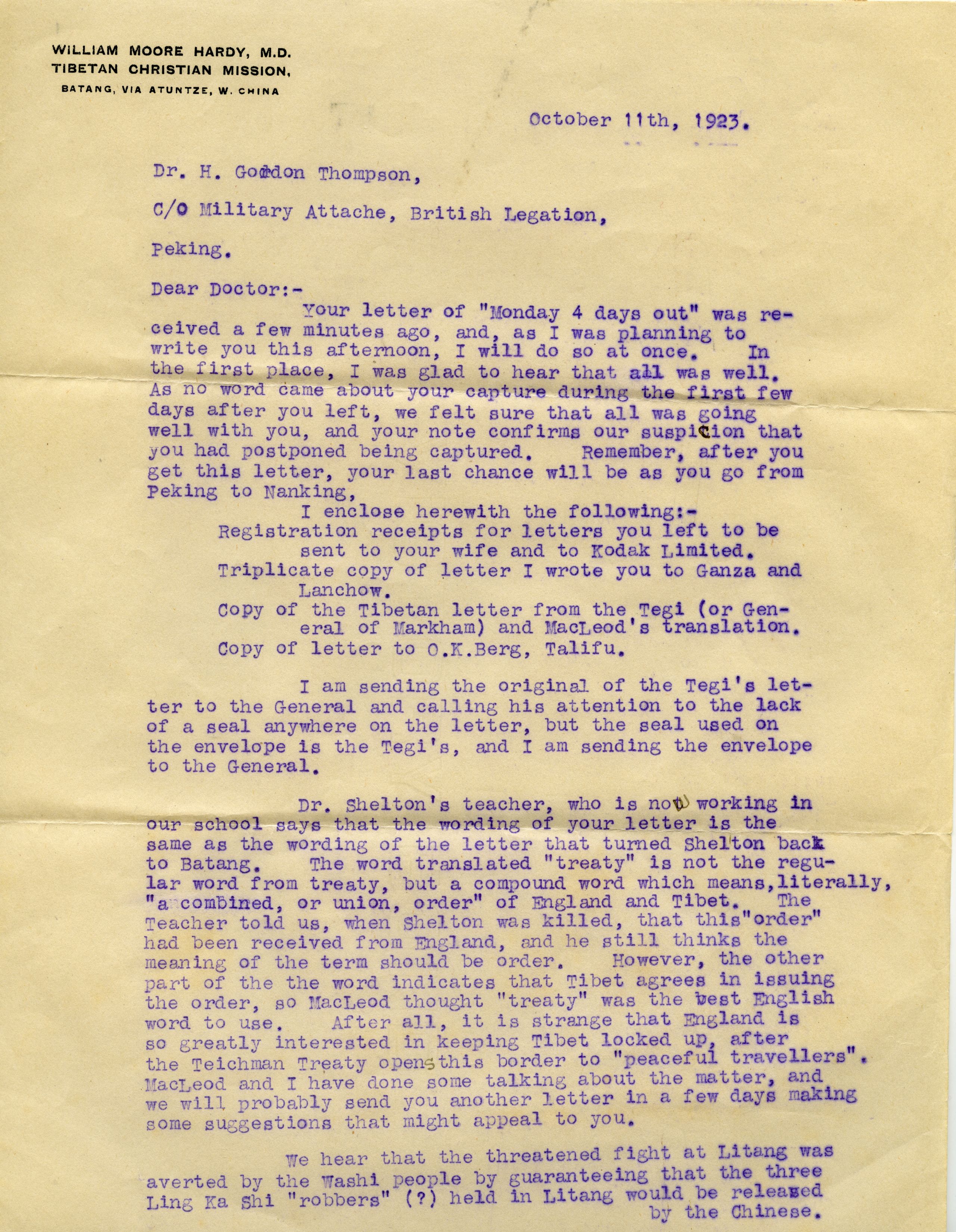

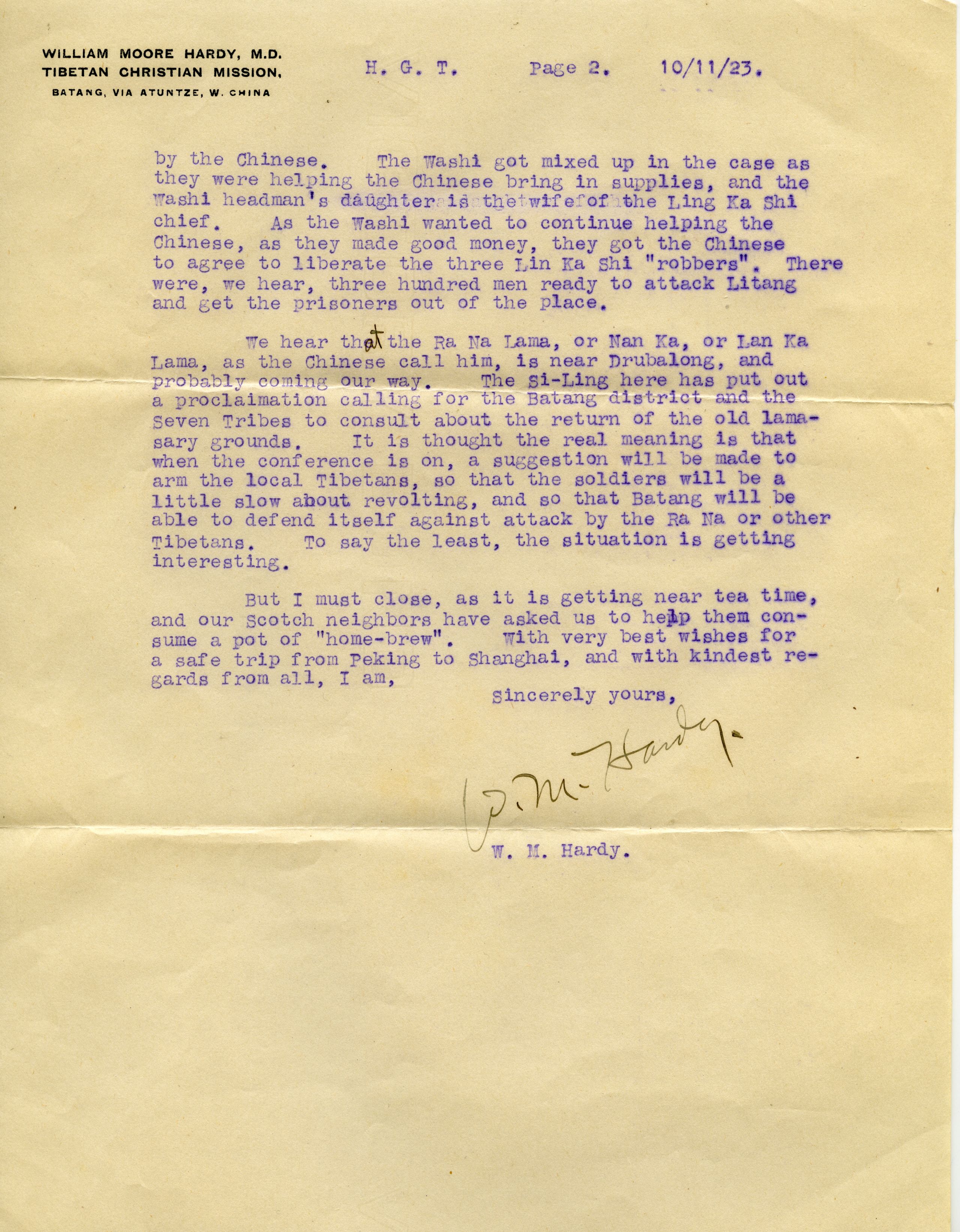

October 11th, 1923.

Dr. H. Gordon Thompson,

C/0 Military Attaché, British Legation,

Peking.

Dear Doctor,

Your letter of "Monday 4 days out" was received a few minutes ago, and, as I was planning to write you this afternoon, I will do so at once. In the first place, I was glad to hear that all was well. As no word came about your capture during the first few days after you left, we felt sure that all was going well with you, and your note confirms our suspicion that you had postponed being captured. Remember, after you get this letter, your last chance will be as you go from Peking to Nanking,

I enclose herewith the following:

- Registration receipts for letters you left to be sent to your wife and to Kodak Limited.

- Triplicate copy of letter I wrote you to Ganza and Lanchow.

- Copy of the Tibetan letter from the Tegi (or General of Markham) and MacLeod's translation.

- Copy of letter to O.K. Berg, Talifu.

I am sending the original of the Tegi's letter to the General and calling his attention to the lack of a seal anywhere on the letter, but the seal used on the envelope is the Tegi's, and I am sending the envelope to the General.

Dr. Shelton's teacher, who is not working in our school says that the wording of your letter is the same as the wording of the letter that turned Shelton back to Batang. The word translated "treaty" is not the regular word from treaty, but a compound word which means, literally, "a combined, or union, order" of England and Tibet. The Teacher told us, when Shelton was killed, that this "order" had been received from England, and he still thinks the meaning of the term should be order. However, the other part of the word indicates that Tibet agrees in issuing the order, so MacLeod thought "treaty" was the best English word to use. After all, it is strange that England is so greatly interested in keeping Tibet locked up, after M the Teichman Treaty opens this border to "peaceful travellers”.

MacLeod and I have done some talking about the matter, and we will probably send you another letter in a few days making some suggestions that might appeal to you.

We hear that the threatened fight at Litang was averted by the Washi people by guaranteeing that the three Ling Ka Shi "robbers" (?) held in Litang would be released by the Chinese. The Tegi got mixed up in the case as they were helping the Chinese bring in supplies, and the Washi headman's daughter is the "wife" of the Ling Ka Shi chief. As the Washi wanted to continue helping the Chinese, as they made good money, they got the Chinese to agree to liberate the three Ling Ka Shi "robbers". There were, we hear, three hundred men ready to attack Litang and get the prisoners out of the place.

We hear that the Ra Na Lama, or Nan Ka, or Lan Ka Lama, as the Chinese call him, is near Drubalong, and probably/ coming our way. The Si-Ling here has put out a proclamation calling for the Batang district and the Seven Tribes to consult about the return of the old lamasery grounds. It is thought the real meaning is that when the conference is on, a suggestion will be made to arm the local Tibetans, so that the soldiers will be a little slow about revolting, and so that Batang will be able to defend itself against attack by the Ra Na or other Tibetans. To say the least, the situation is getting interesting.

But I must close, as it is getting near tea time, and our Scotch neighbours have asked us to help them consume a pot of "home-brew". With very best wishes for a safe trip from Peking to Shanghai, and with kindest regards from all, I am,

Sincerely yours,

W.M. Hardy.

WILLIAM MOORE HARDY, M.D.

TIBETAN CHRISTIAN MISSION,

BATANG, VIA ATUNTZE, W. CHINA

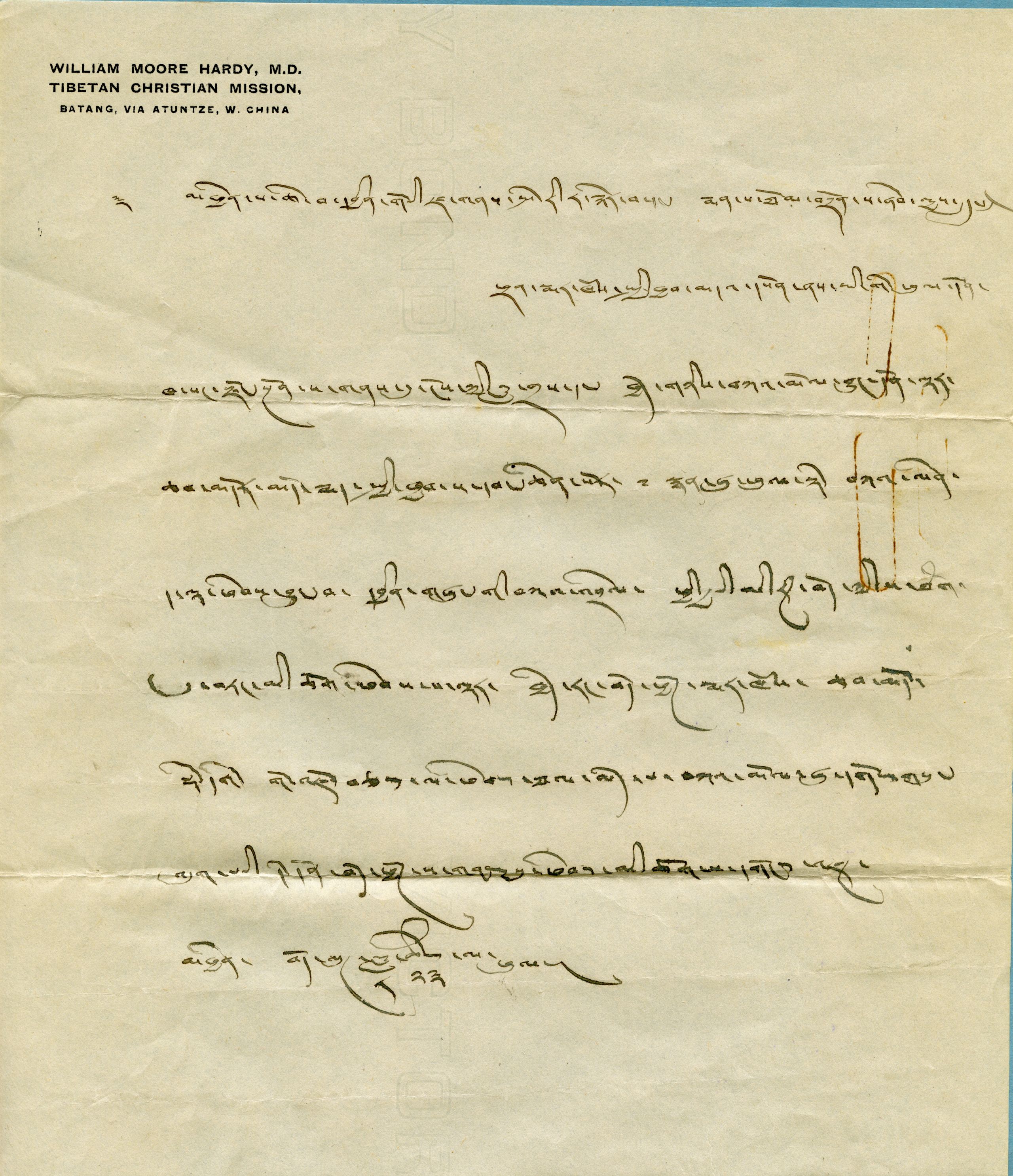

To Mr. Pereira and Dr. Thompson:-

A letter from the Markham General

According to a recent conference between my servant and yourselves at Dzong Ngen, I have sent word to the Galon Lama at Lower Chambdo, and an answer has now arrived, and says that according to a treaty with the English Government, which prohibits foreigners entering Tibet, you may not enter Tibetan territory at Markham, Chambdo, Derge, or Gonjo.

Please know and bear in mind that the answer to the request of your conference, which has been reported, means that you are not permitted to enter Tibet at any point whatsoever.

Tibetan Eighth month, twenty-third day

(Received in Batang Oct, 7th, 1923. Translated by R.A. MacLeod.)

Day Eighty-one October 5th 1923 Batang to Me Li Ting - 9½ miles

They now prepared for the most difficult and most risky part of the journey — the stage to Kanze (now known as Garze).

“Between Batang and Kanze, lies the territory of three important Tibetan tribes: - the Leng kashi, the Washi (or Wa Qie), and the Nyarong. It had been our intention to reach Kanze by a circuitous route more to the north, parallel to the Yangtze but just inside the Tibetan frontier. As the Tibetan Magistrate at Gartok has refused us permission, this route is ruled out.”

(Note: Although HGT refers to them as “Tibetan tribes”, it now seems more likely that these are people from different areas rather than different ethnic groups. Lengqi is a town in the Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Sichuan; Wa Qie is a remote high‑altitude region (42 kms northeast of Hongyuan and 60km south to the first bend of the Yellow River) on the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau with grasslands, and meandering rivers that cross them and some extensive marshlands; and Nyarong is a Tibetan historical region located in Eastern Kham. It is generally equated with modern Xinlong County, which is called Nyarong in Tibetan, though the traditional region also includes parts of Litang County and Baiyü County.)

Letter from WM Hardy Oct 11 1923

Letter from WM Hardy Oct 11 1923

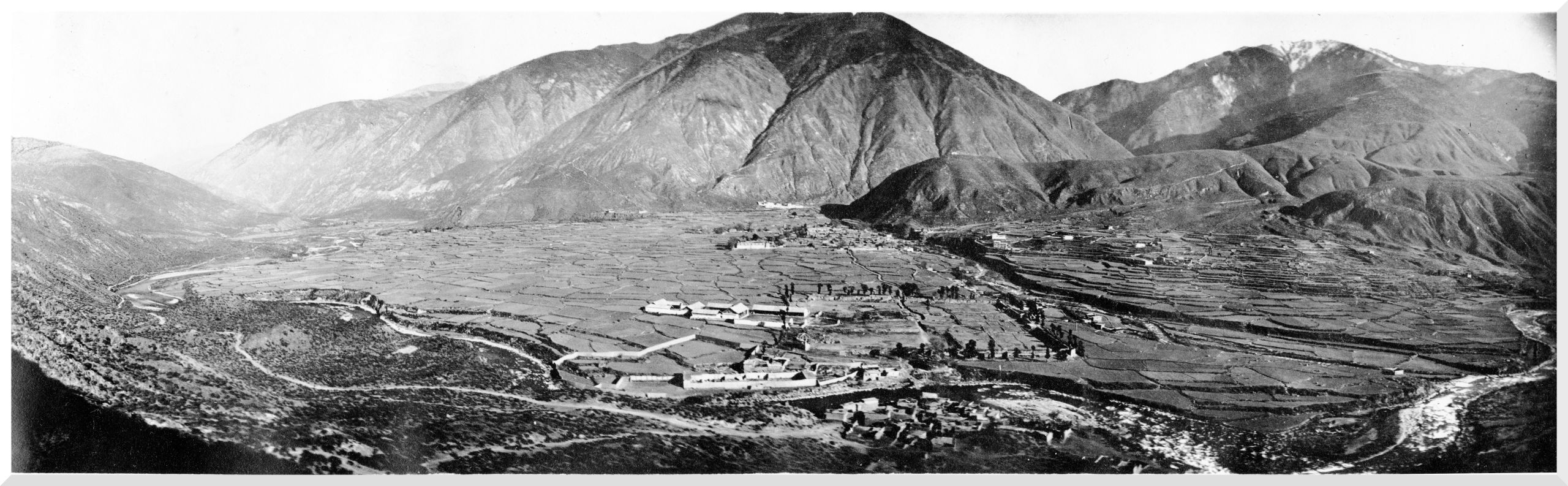

Batang from across the big river. The lamasery is near the centre of the picture and the hill with the white fort

Batang from across the big river. The lamasery is near the centre of the picture and the hill with the white fort

“The usual road due east to Tatsienlu viâ Litang was closed by brigand bands of Lengkashi, who were reported to be attacking Litang. At first it was reported to be between the Nanka Lama men and the Batang Chinese soldiers - then it was said to be the Leng Kashi people, and not the Nanka lama men. Two soldiers with bullet wounds were brought into the Hospital, and one dead soldier was brought into the town. It is difficult to tell truth from rumour. As we were quite determined not to return by the way that we had come, the suggestion was made that we should attempt to cross the Washi country. This was the more attractive option as the Washi country had not previously been crossed by Europeans, yet it was known that the source of several large tributaries of the Yalung, which in turn pours its waters into the Yangtze, were in this hitherto unexplored country”.

“The Washi country is divided into three districts, called the Monia or Mao Ya, the Dai Yung or Ko tun, and the Tsong Hsi, each with its separate chief, but all owing a loose allegiance to the Queen. The Queen of the Washi, who had been helped by Mr. MacLeod and Dr Hardy of the Tibetan Christian Mission when she had been a fugitive in Batang, said that her people could take them through to Kanze. She thought the road was all right, but that it would be best to keep their eyes open”.

They still had considerable difficulty with the officials at Batang, who said the route would be difficult as they would have to cross high ranges with the winter now approaching. They also said it would be risky, because there was no kind of rule or order in the region they would have to traverse. The Chinese magistrate tried to make the Washi muleteers whom GP had engaged, give a guarantee for their safety. This they naturally refused to give, and after much dispute both GP and HGT sent letters to the magistrate and the general relieving them of all responsibility.

“At last we could set off. The Moore's, Duncan’s, Dr. Hardy and his 2 elder children escorted us to the gate of the town, and once more we are on the road”.

“We are travelling mostly eastwards, and have climbed 1260 ft in altitude. It began to rain before we left Batang and has carried on all afternoon with a steady drizzle. It is also quite a lot colder. We have followed the stream which supplies Batang with water and as we went up the valley, we passed the place where the Amban Feng Lama was killed in 1905. It is marked by an inscription cut out in the rock. We crossed the stream – a small torrent - four times over very rickety log bridges. Pereira said that at the one at the top of the valley - a handful of men could hold up an army”.

At 6½ miles the valley became more open and at 9 miles they reached the hamlet of Ba-chiang-hsü with eight families. After 9½ miles they reached Me Li Ting (only two houses at 9,536 ft.).

“We are glad to be under cover and out of the rain”.

Their miscellaneous collection of transport animals — donkeys, mules and ponies — were now changed for yaks.

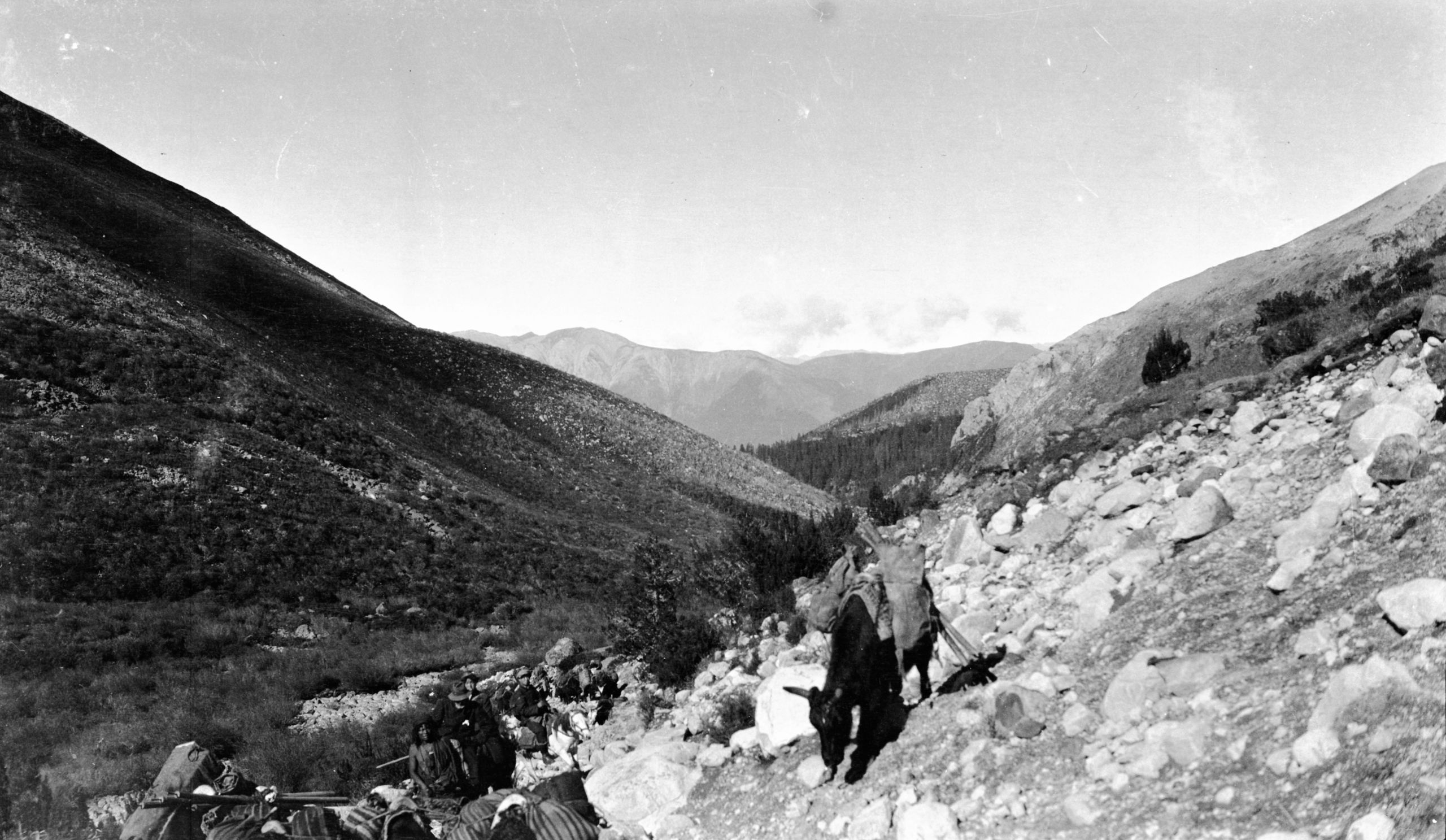

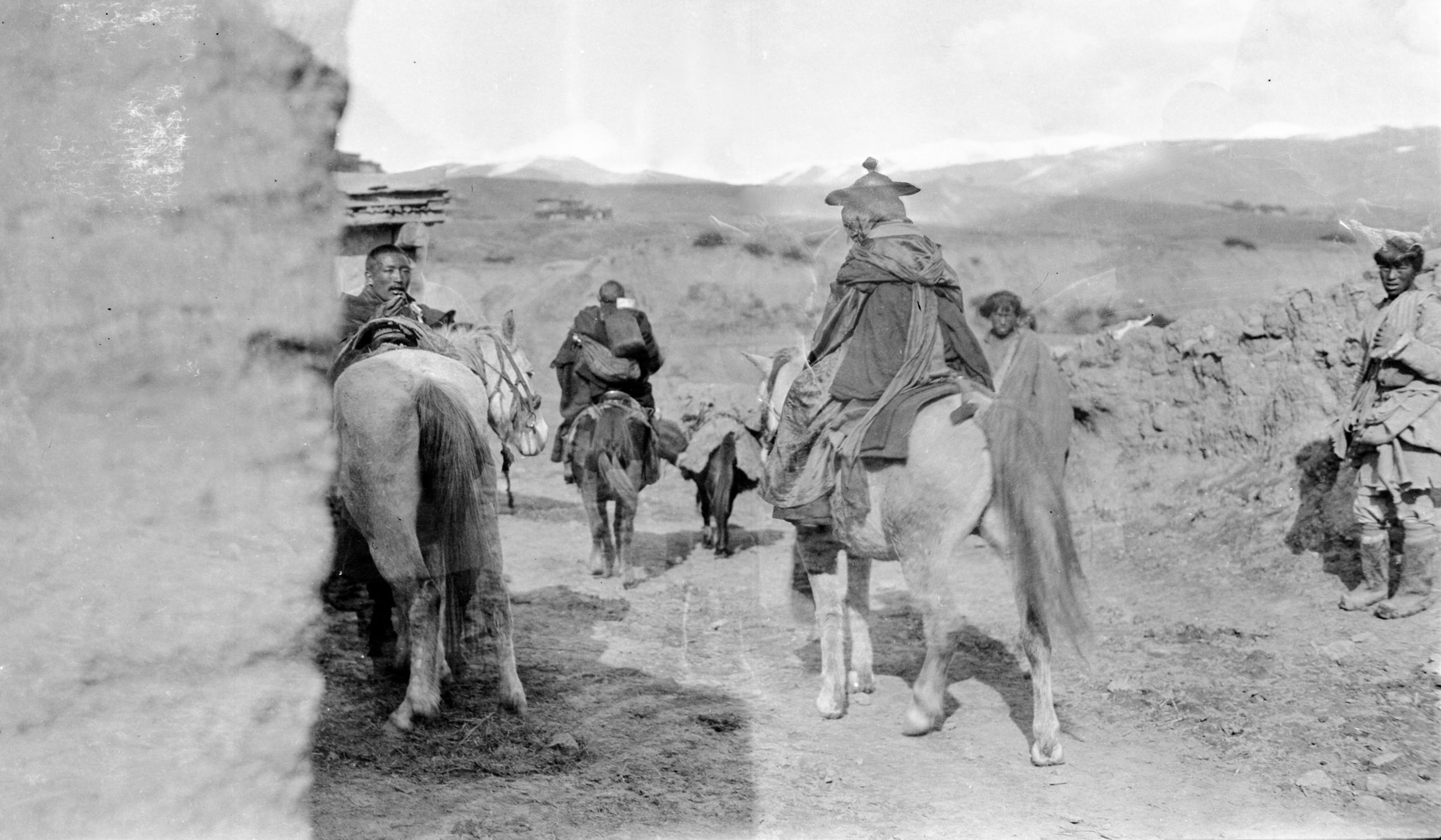

Looking back towards Ba-tang at the junction of the large and small Litang roads

Looking back towards Ba-tang at the junction of the large and small Litang roads

Day eighty-two October 6th 1923 Me Li Ting to Pang Wa Mo (or Pongdramo) 6½ miles

“We started out this morning at 10 minutes past 5 - and have come steadily up the valley, still following the stream which goes down to Batang. There was first a steep ascent up the stony hill- side, the valley narrowing between high fir-covered hills. After 1¾ miles, we passed the place where the fight between Chinese soldiers and the Nanka Lama had taken place 4 days ago and we could see traces of it on the road. The path then descended slightly crossing a side stream full of boulders. After that it continued up the valley with the Ba Chu, a small raging torrent, always on the right, to Pang Wa Mo (Pongdramo), two or three ruined houses on a clearing. The day was cloudy in the morning, but the sun came out in the afternoon.

The yak were quite unsuited for this enclosed country. They were constantly running in all directions and shedding their loads.

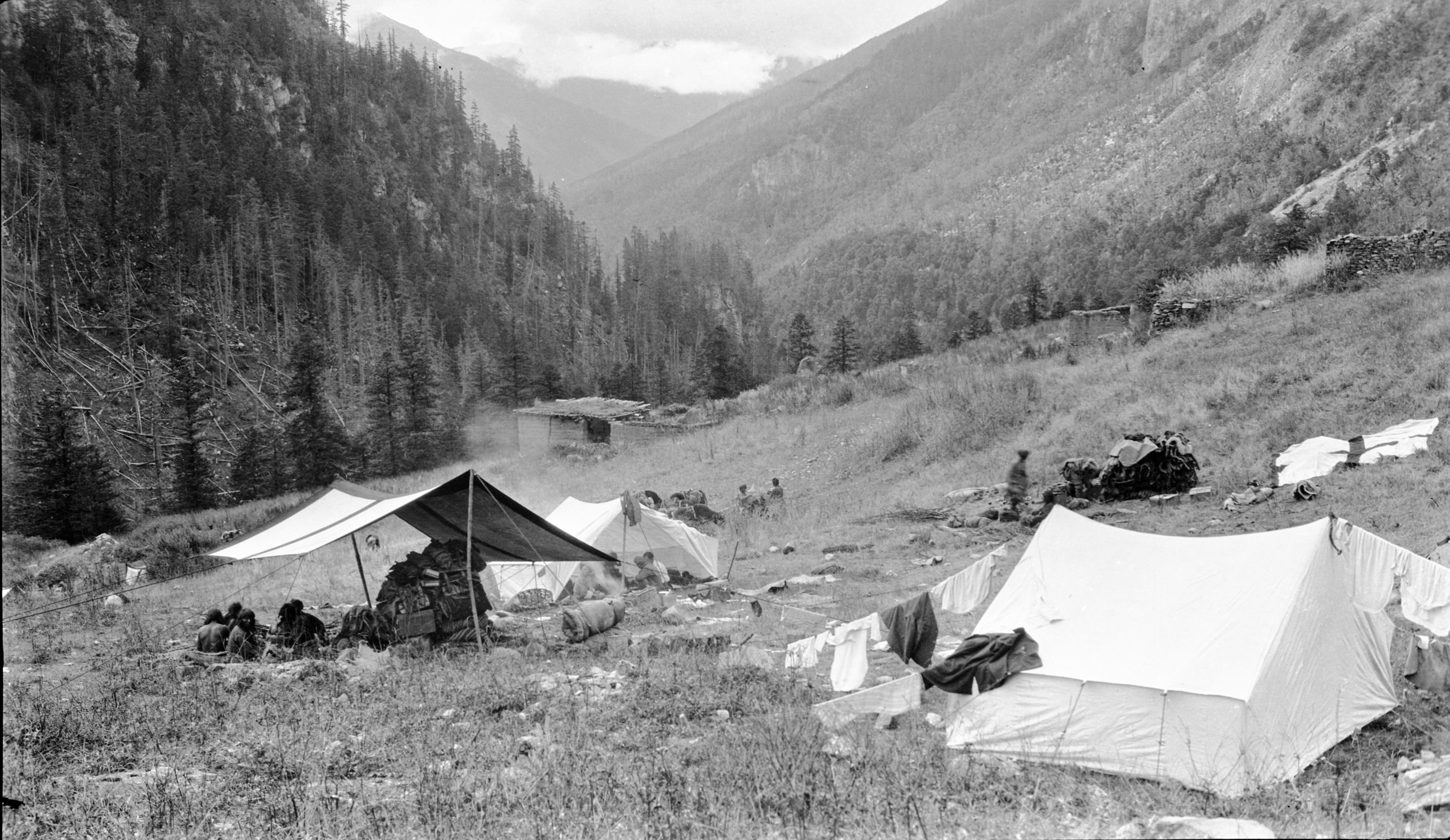

“We had to cross a torrent which was going to join the main stream. The Yak were very obstinate and one of them took a plunge with my box of photographic material and the box containing my warm clothing. However, we were only about 15 minutes from Pang Wa Mo (12,231 ft.) where we were to camp. We arrived at 1.30 p.m. and I was able to empty the two boxes and put the things out to dry.

"The tents we had made at Batang, (one for GP and HGT and one for the two boys) are not very strong, and the one that Pereira and I are using has a hole in it already".

With only a single fly sheet, they were bitterly cold, and the cold was increasing, as not only was winter approaching but they were rising higher. However, there was no wind, the weather was fine, and the sun came out. The tents were fixed up and seemed all right. HGT was able to empty the saturated boxes and dry off the contents and their things were soon dry.

1st camp at Pang Wa Mo after leaving Batang in Washi country

1st camp at Pang Wa Mo after leaving Batang in Washi country

Day eighty-three Sunday October 7th 1923 Pang Wa Mo to Sum baa ala - 12 miles

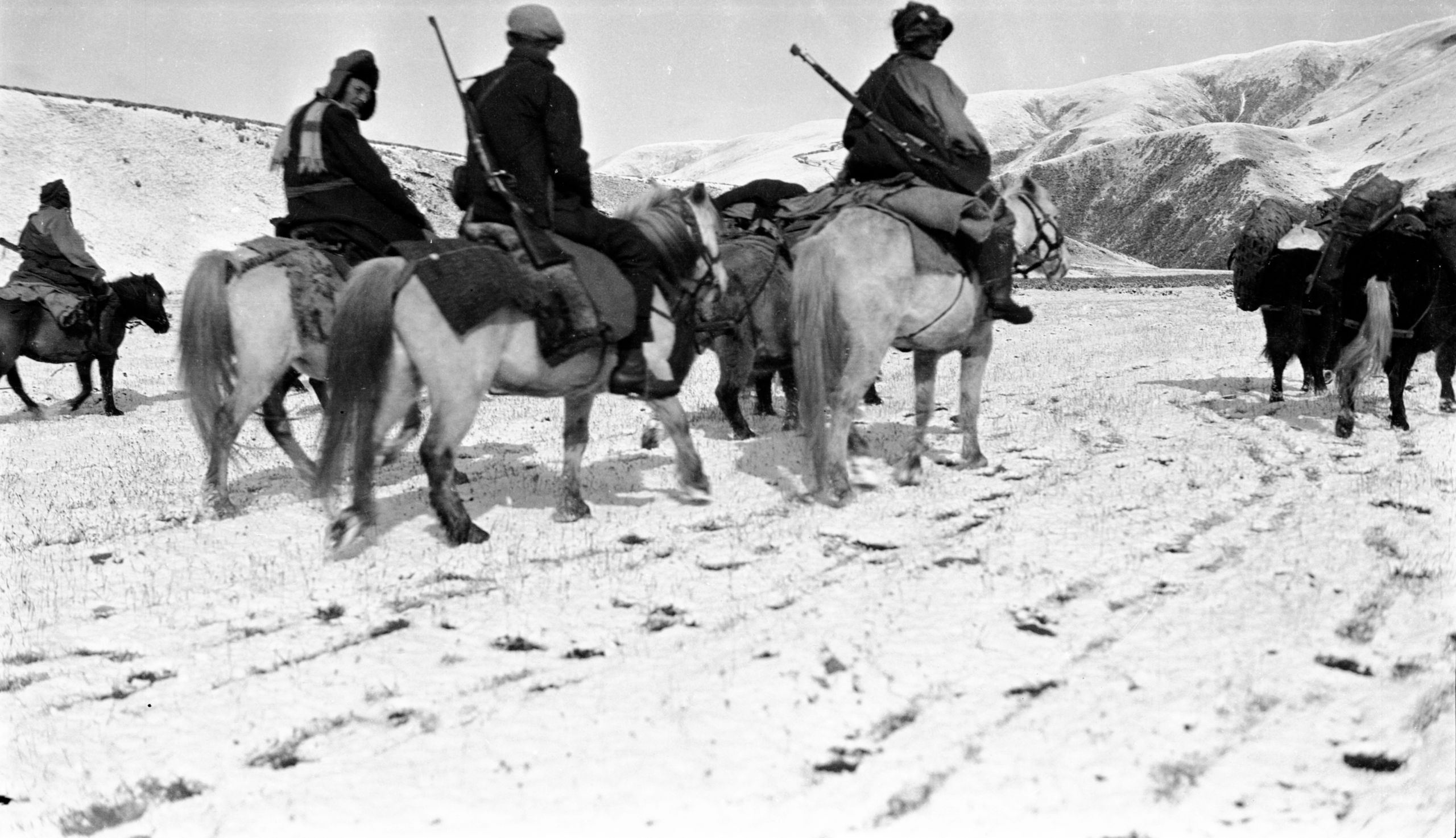

“We made a good start this morning at 7 a.m., following the Litang main road for about 6 miles. In our group, for the first time on the convoy, there were now 5 mounted Washi militia armed with Mauser rifles, and the two boys, one with a rifle, and the other with a shot gun. We also had about two dozen Yak carrying baggage and salt, etc.

“Two of the Washi went on ahead scouting. The valley was well wooded but not as enclosed as yesterday. The path continued up alongside the Ba Chu, ascending a steep narrow valley between high hills. At 4¾ miles the limit of trees was reached and a steep climb over stony open ground followed. At about 9:30 we came to the place where their road branched off from the Litang main road. We turned N.E. and climbed a long wide-open valley, till at last after 7½ miles we the pass called Ta Sa Shan by the Chinese, and Tsung Bung-a La by the Tibetans”.

“As we reached the pass, we met about 40 soldiers who were returning to Batang after hunting for the Kanka Lama's men who were supposed to be the band who killed and wounded the soldiers 4 days ago. I scribbled a note to Dr. Hardy to say where we were and that all was going well and I gave it to one of the soldiers who knew Dr Hardy. He knew Mr. MacLeod so I told him to deliver it to him”.

Taking the boiling point at summit of Cha-ga-la. Chinese boy, Tibetan boy and GP

Taking the boiling point at summit of Cha-ga-la. Chinese boy, Tibetan boy and GP

“We rested up to measure the height by taking the boiling point. The apparatus was fixed up but match after match went out with the wind, till only one was left. I stripped off my Burberry and threw if over the heads of GP and the boys. GP was lying flat on the ground watching the thermometer. The match was struck inside this “tent”, and succeeded. The height found to be 15,610 ft. This is the divide between the Ba Chu (or Li Chu) and the Ding Chu and the highest point we have reached on the journey from Yunnan.

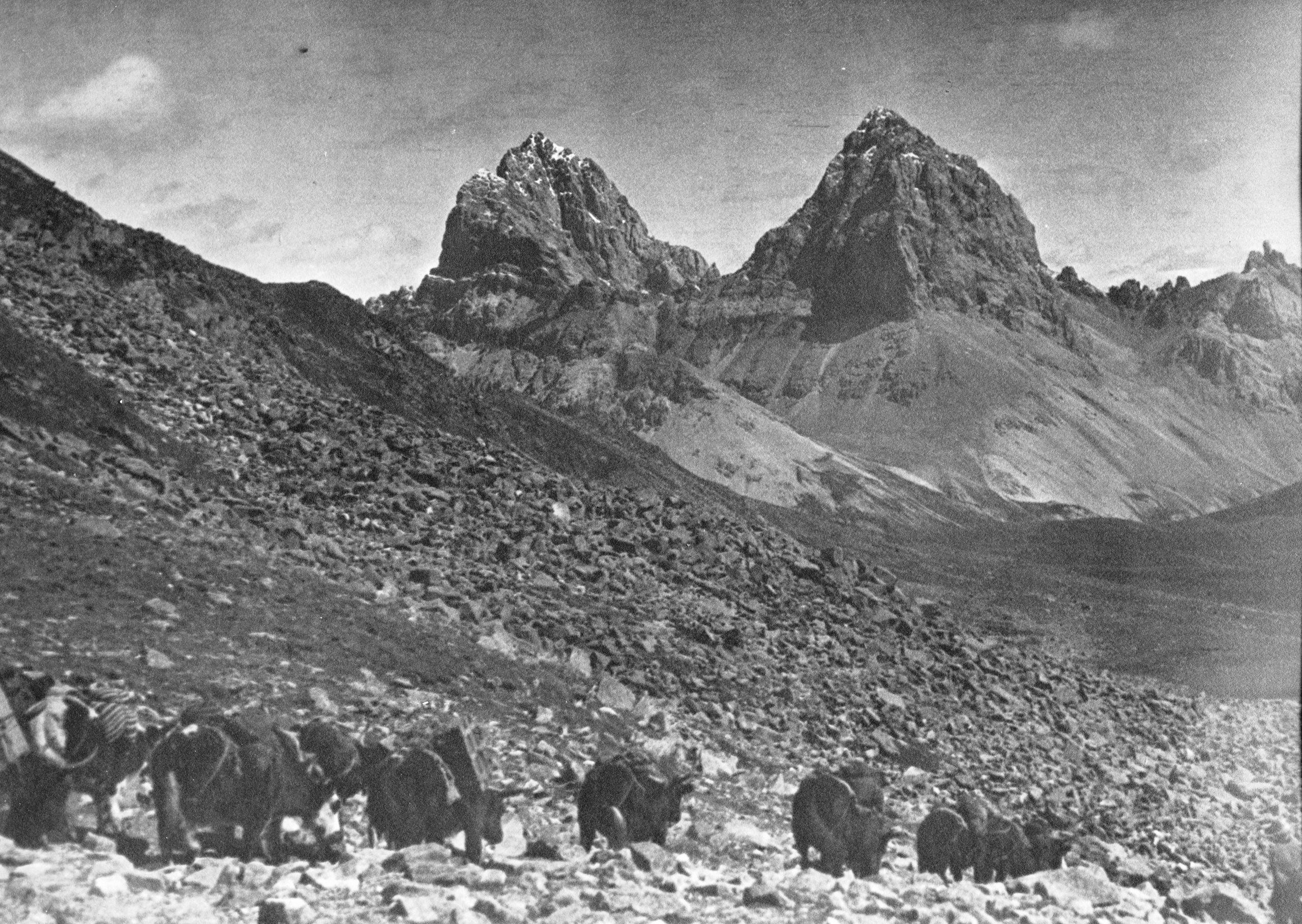

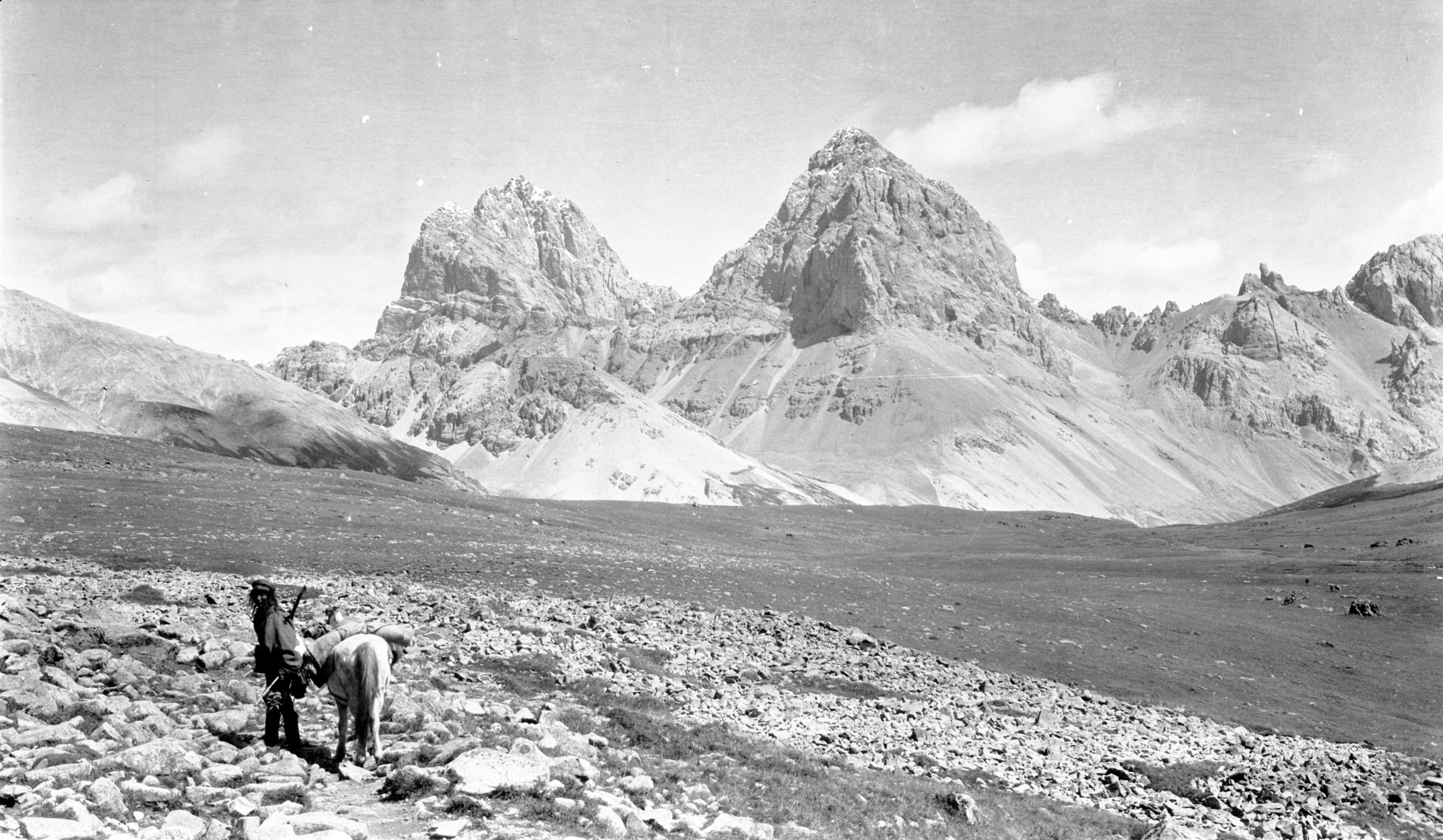

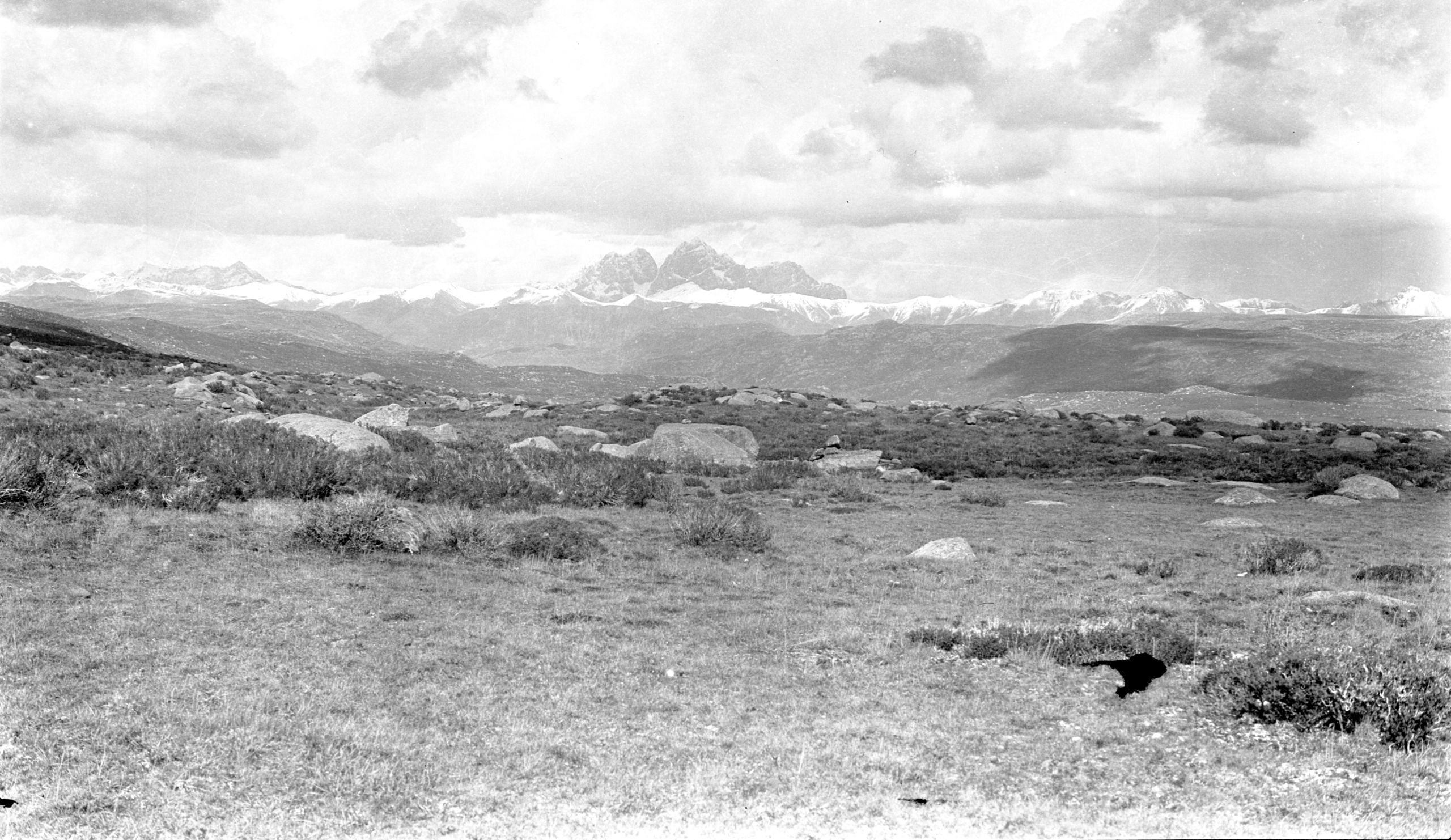

“There was some snow on the ground and it was very cold - pools were frozen. As we came down from the pass, two peaks with snow on their summits came into sight. Then we began to descend, and soon I had to take off my fur coat it was so warm. At 12.30 we arrived at the camping place we called the Sum baa ala camp (13,903 ft.) - a beautiful spot by a stream a tributary of what was sometimes called by the Washi Tibetans, the Ding Chu and at other times the Ta So. In front was a range of snow mountains, behind it was the valley we had descended.

“We had lunch and a good rest. It is Sunday and my thoughts are with all at Yunnan-fu. Now I must stop and have a read and probably snooze!!”

Twin peaks from pass called Ta-so-shan (chinese) and Tsung pang a la (Tibetan)

Twin peaks from pass called Ta-so-shan (chinese) and Tsung pang a la (Tibetan)

Twin peaks and entrance to the Sun ba-a-la valley

Twin peaks and entrance to the Sun ba-a-la valley

Camping in the Sum ba-ala valley (Washi country) on the Tibetan border

Camping in the Sum ba-ala valley (Washi country) on the Tibetan border

“From the camp we got a bearing, 120°, to a high snowy peak 8 to 10 miles away. The highest peak in the range in front is the “Pik des Goudins”, so called after the French priest who first discovered it was 19,000 to 25,000 ft. high and its Tibetan name is Ga mu ni.

Day eighty-four October 8th 1923 Sum baa ala to Ta Soh Kok - 13¼ miles

"We have had a glorious morning, starting at 7.10 a.m. and getting in at 12.35 mid-day. When we got up at 5.30 there was sharp frost on the ground, and my sponge had frozen hard. However, the valley in which we were camped lay East-West so the sun was soon shining on us and warming us up”.

“We continued our descent down the valley which we entered yesterday. The Washi headman told us that he had news that the Tibetans were attacking the Chinese garrison at Litang and that probably the Lan Ka Shi people would be on the warpath on our road. However, he thought it was best to go on, and see how things were by means of scouts”.

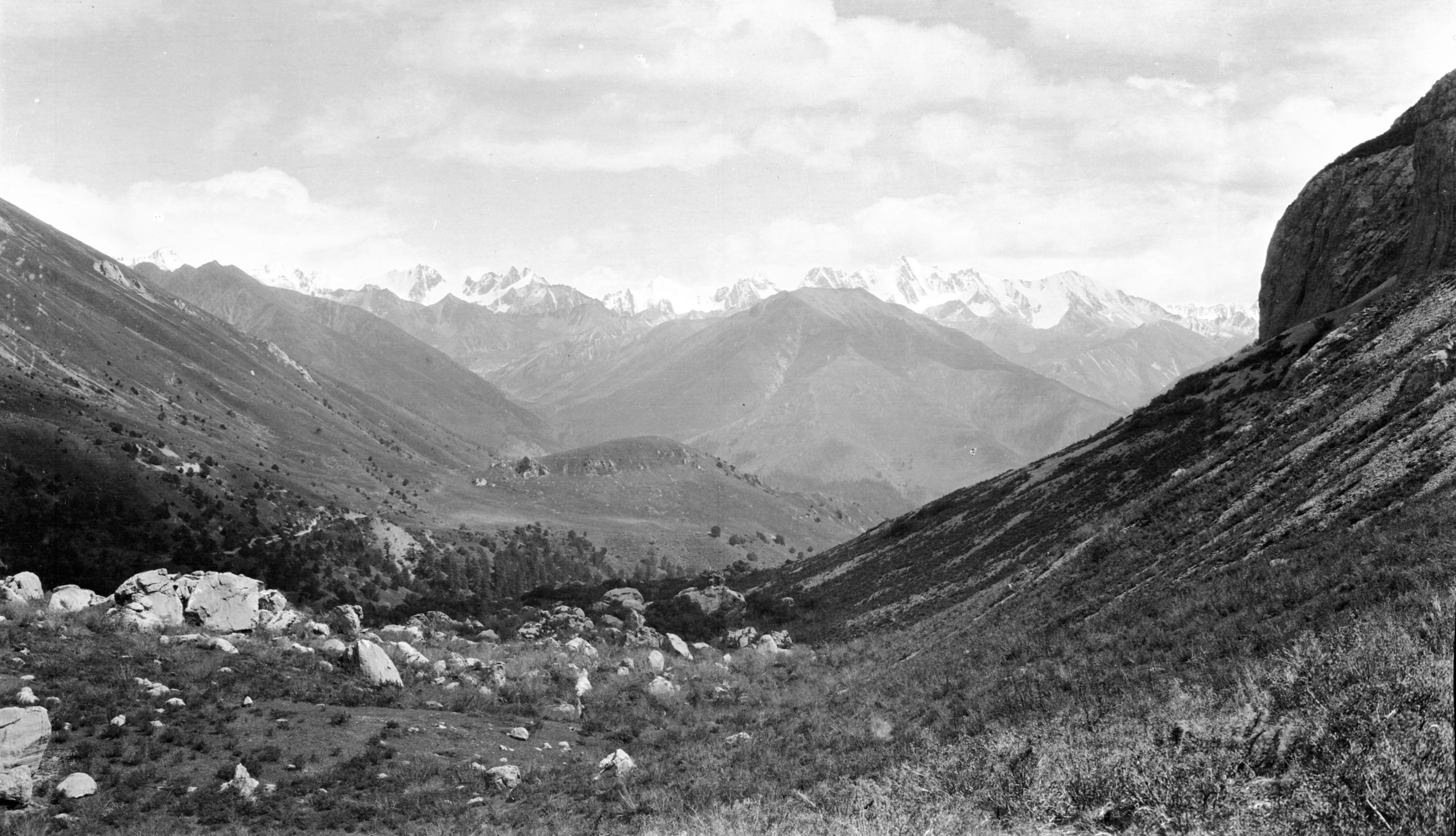

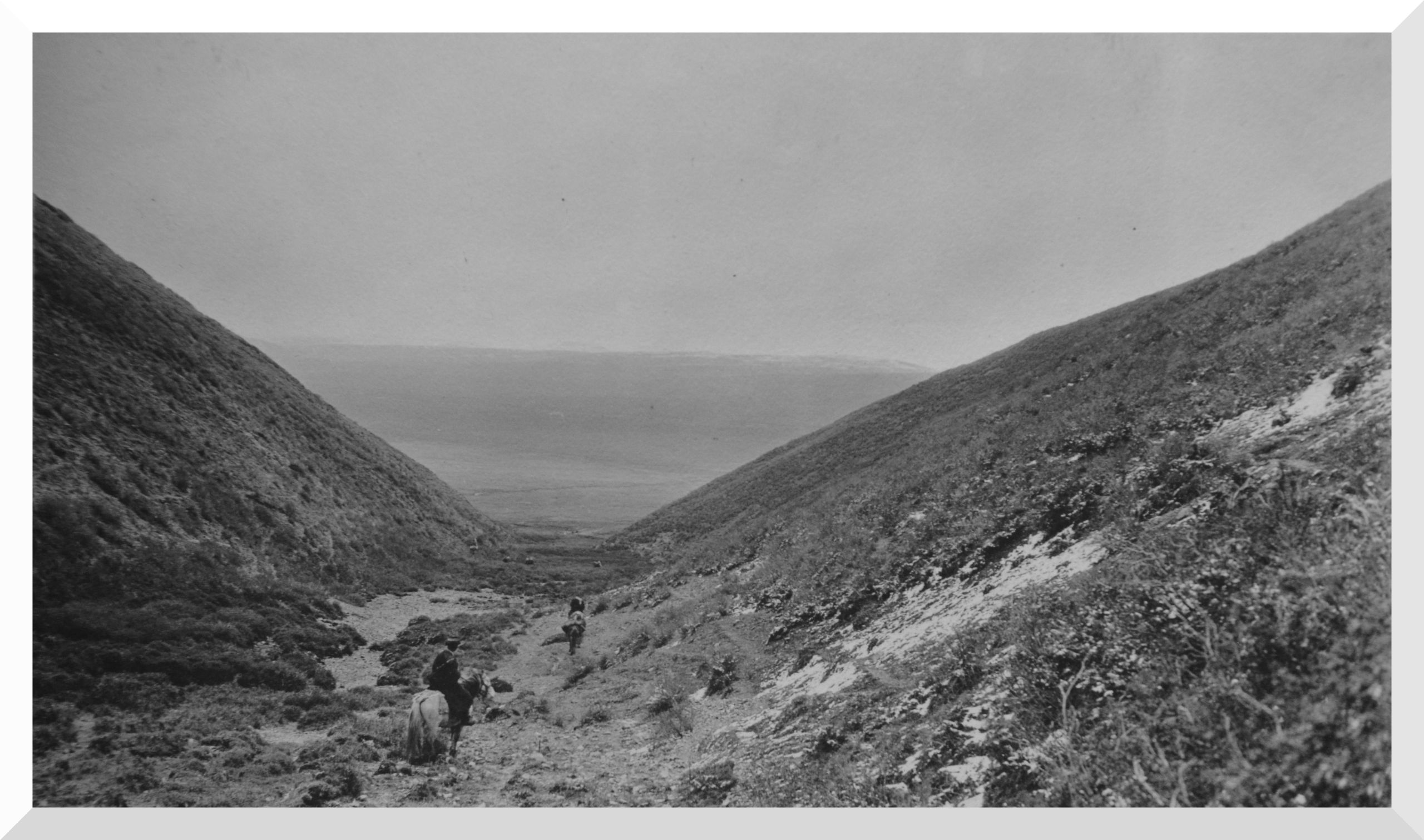

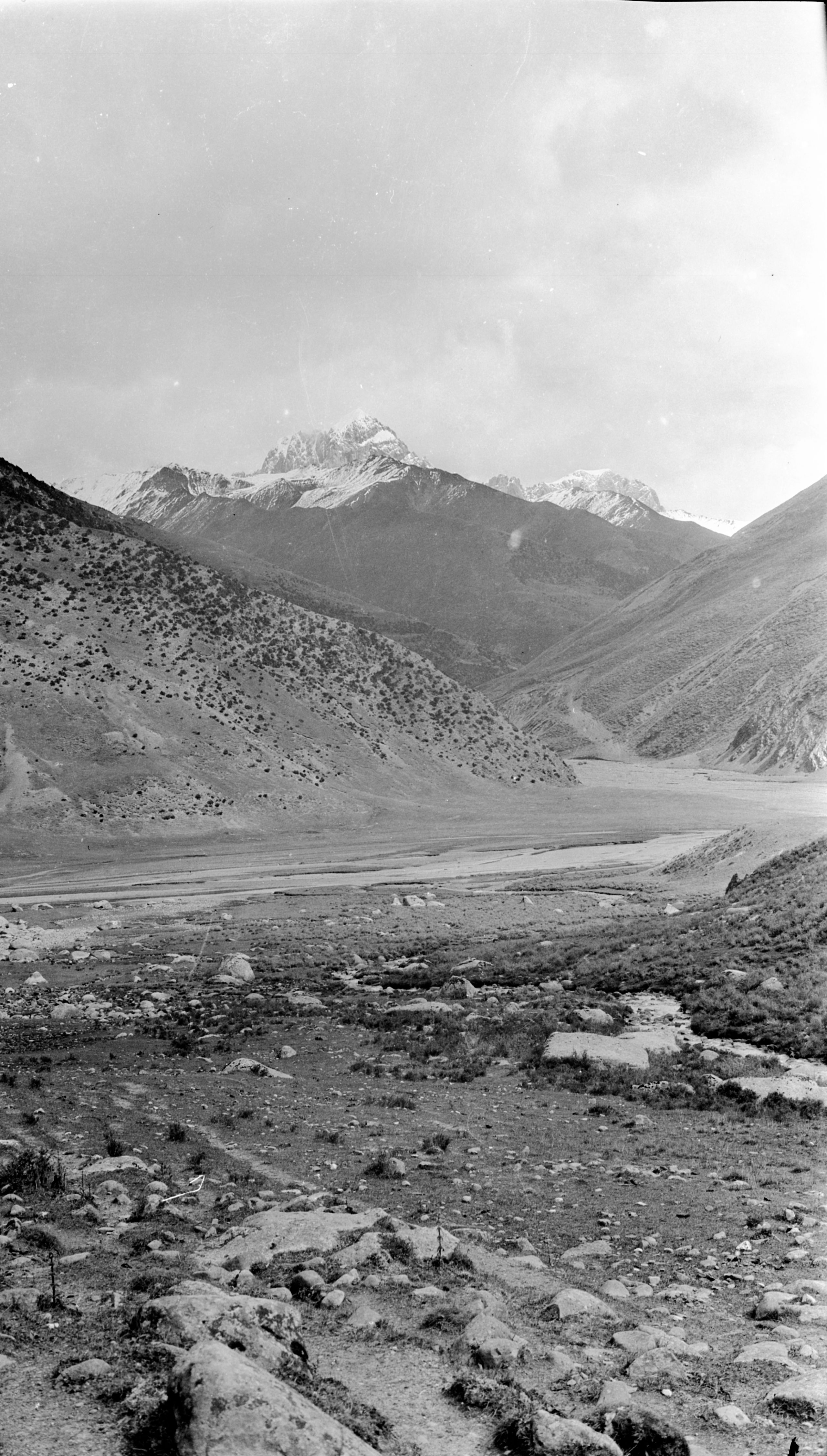

Looking up towards the Ding Chu valley. In the lower altitude parts of Washi country

Looking up towards the Ding Chu valley. In the lower altitude parts of Washi country

“After following the Sum baa ala valley down, we came to a big valley lying at right angles, North-South. At the junction were the foundations of six houses which had been burnt out 4 years ago. All along our route we have seen the remains of houses which were said to have been destroyed by Tibetans. Flowing down the N & S valley was the Ding Chu River, which was joined to the Ya Lung and some other tributary of the Yangtze. They now entered the Ding Chiu valley (or La ma ya). After crossing the river several times, we came to a rise from which there was a good view of two snow covered peaks between which their Washi muleteers told us the road passed from the Ling Ka Shi country to Litang.

“When we were about 2/3rds of the way along the Ding Chu valley we saw a large convoy coming in the opposite direction. It was the Litang convoy with about 100 soldiers - a large number of Yak, and the new official on his way to Batang and Yen Chung. He told us that Litang was peaceful, as was the road over which he had come. His name was Chong. He promised to convey a message to Hardy & Mr. MacLeod to say we were so far safe on our journey. He seemed a very pleasant man and most courteous”.

Continuing up the Ding Chu (or Tung Chien) river valley they came to the place where the road branched off to Ling Ka Shi country up a side valley towards the snow mountains. The river was forded three times. It ran in a stony bed and was 80 yards wide and 2 feet deep. They camped at the foot of the valley.

Day eighty-five October 9th 1923 Ta Soh Kok to La Ma Ya valley (Yew Chin in Tibetan) - 15 miles

“In the morning we set off about 10 minutes to 7 and continued up the grassy and often rocky and marshy Ding Chu valley for 7 miles until we reached the Chaga la pass at the top (14,981 ft.); the divide between the Ding Chu and Li Chu. It was also the boundary between the Batang district and the Washi country. We are now in the country of the Monia Washi and near the sources of origin of the Li Chu or Litang River”.

View of confluence of Sumbala and Ding-chu

View of confluence of Sumbala and Ding-chu

The top of the valley divided into 4 small valleys and the pass was at the top of the third small valley from the right. Looking back they could see some snow covered peaks and one in particular rose like the tower of a large cathedral, but the top, instead of being square, tapered to a point.

Snow covered peaks taken from Sun ba ala valley

Snow covered peaks taken from Sun ba ala valley

“I tried to take a photo of some of the muleteers, but they were very frightened of the camera and would not do anything in the way of standing so that I could get the mountains in the background. They have a superstition that if anyone possesses anything connected with them e.g. a few hairs of their head, they could bewitch them”.

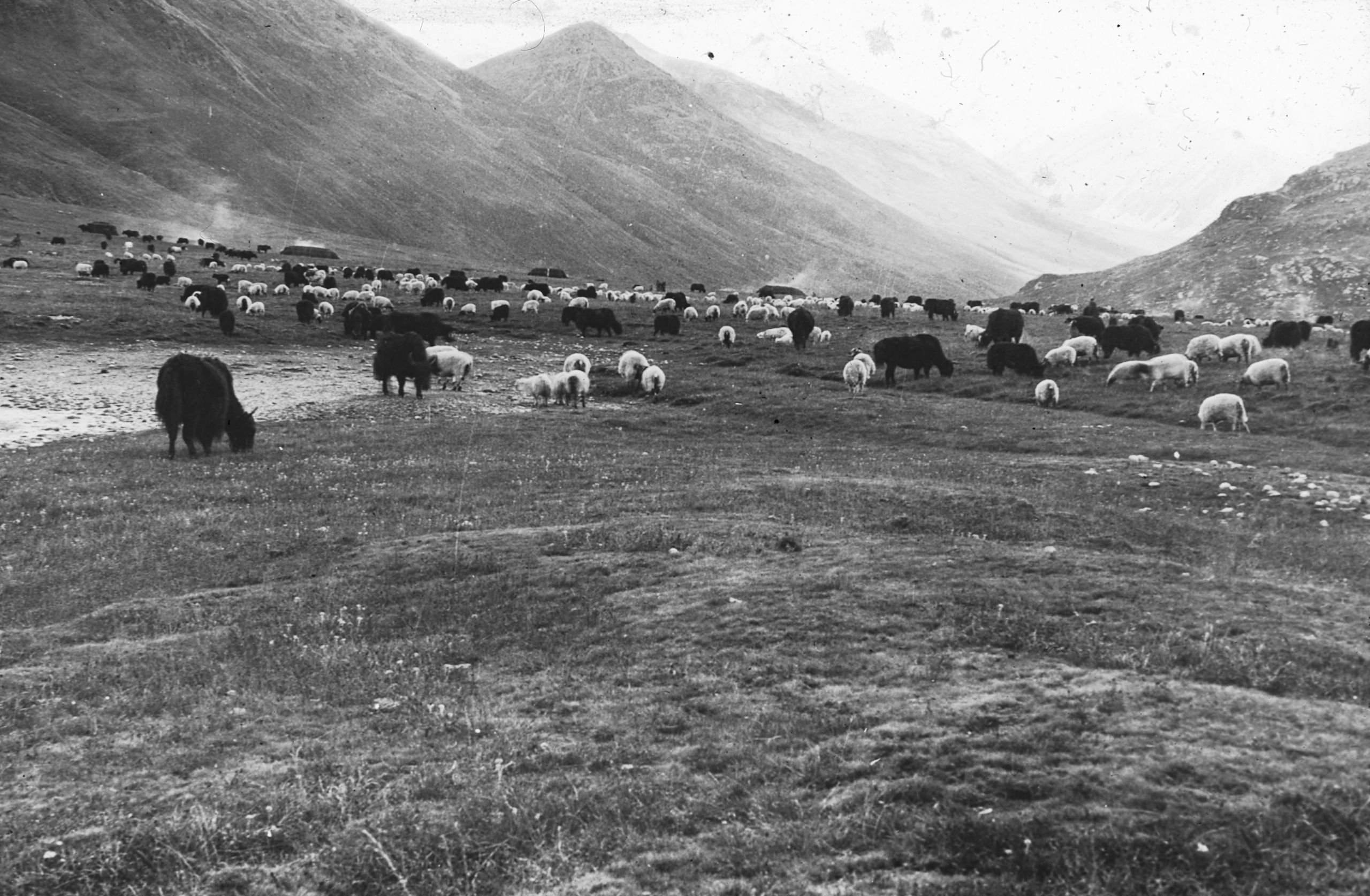

Washi camp at the source of the La ma ya river. Nai ya snow mountains in background

Washi camp at the source of the La ma ya river. Nai ya snow mountains in background

"After crossing the pass. We descended into a large open valley, which, at the south-west end was divided into 2 small valleys, down which came two streams. We followed a small stream which in turn emptied into the Shara Chu, one of the three main sources of the Litang or Ding Chu River. Called in Tibetan Yeu Chin. As we came into the large open valley we could see across the river a large Tibetan encampment with 20 black tents and 2 white ones (for Lamas), about 800 yak and a similar number of sheep.”

“We crossed the river and passed through the edge of the camp where the animals were grazing. I jumped off my pony and tried to get a photo, but 2 of the mounted muleteers tried to stop me. They gesticulated in Tibetan for me to move on and follow the caravan. I threw the reins of my pony to them, and said “take my pony”. I quickly fixed up the camera, and before they knew what had happened I pressed the button. I was not near enough to the tents to get a good view of them. Behind the sheep and yak was the mountainside and behind that a great range of snow covered peaks. The highest called Nai Ya which must be at least 20,000 ft. high”.

Valley of La ma ya river looking south with Washi tents in the distance

Valley of La ma ya river looking south with Washi tents in the distance

They passed quickly through the encampment and followed the La Ma Ya River for about 1 mile and then encamped (13,450 ft.), arriving at 1 p.m.

HGT wrote in his journal:

“We are now in the Washi country and the risk of brigands is very small, because these people we are travelling with are in their own country and nobody would dare to attack them. It is the Batang and Litang districts which are bad and we are out of the Batang district and into the Washi country, at least 4 days journey from Litang.”:

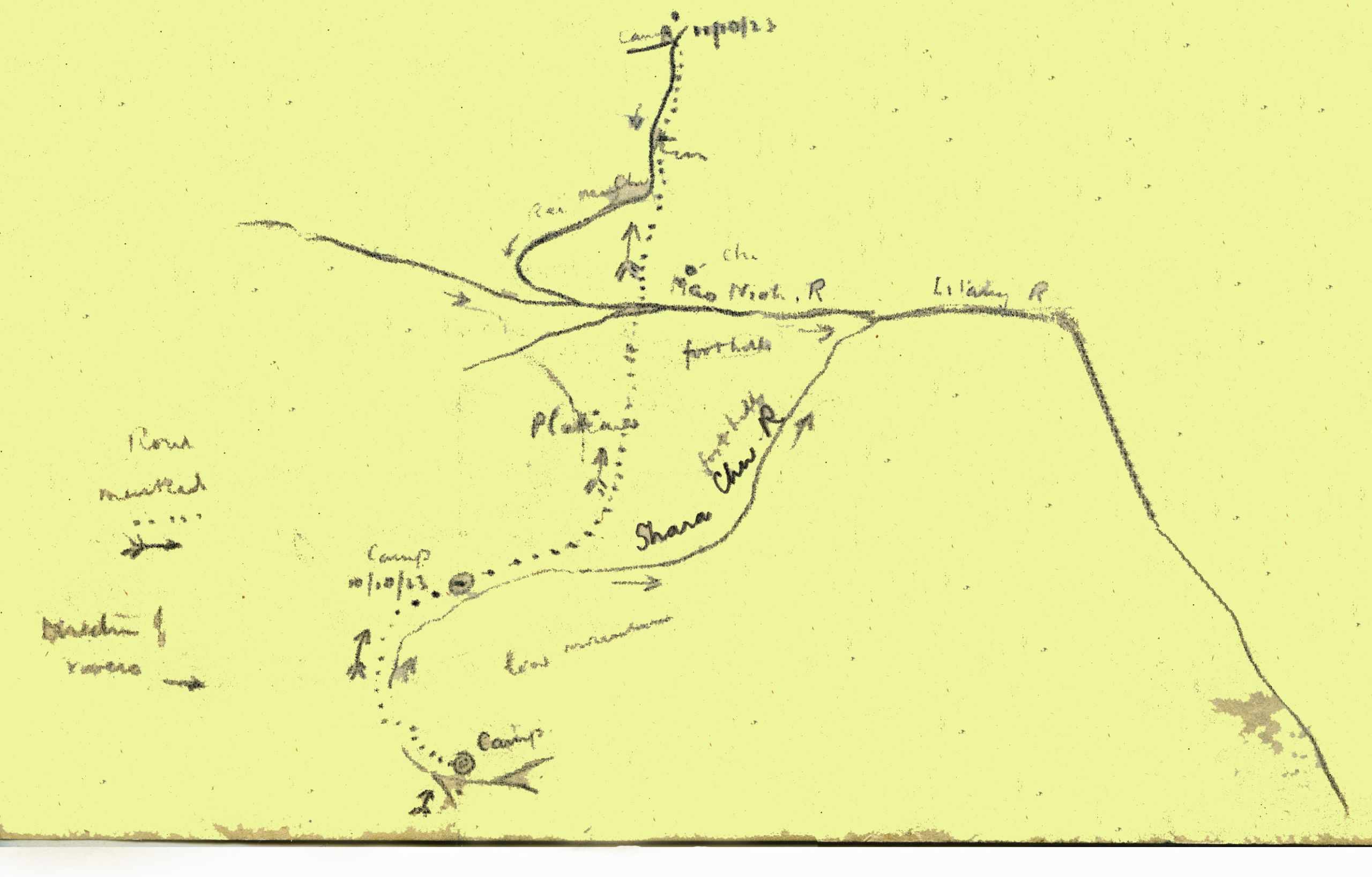

Day Eighty-six October 10th 1923 La Ma Ya valley to Shara chu - 3¾ miles

“An easy day’s journey only 3¾ miles. Starting at 7:30 a.m. we crossed the La Ma Ya River again and skirting the foothills arrived at 9 o’clock at this Washi encampment, the muleteers are anxious to give the yak a rest. They cannot go for more than five or six days without a halt and they were exchanging three which are somewhat fatigued. The yak seem to be very timid creatures. But it is noticeable that when the muleteers approached them to adjust their loads, they are quite careful in their approach – though whether it is so as not to startle the yak and make them run away, or whether it is not to arouse their ire, they couldn’t say. It is said, that when roused, they can be very fierce.

“The valley through which we have been travelling the last day or two has been very devoid of trees – the hills rock, with a coarse grass in between – the lower part to the valley near the river covered with a low scrub, where the ground is marshy. Between the marshy parts at the foot of the hills, there is plenty of good grazing ground for the yak and sheep. At the place where we are now in camp in the Shara-chu valley (13,224 ft.), the Tibetan women and children were busy digging up a root. It grows in the grassy ground and has a tuberous appearance. They said it is good to eat”.

Washi women and children

Washi women and children

Children digging for roots outside a Washi tent

Children digging for roots outside a Washi tent

“As we crossed the river today, we saw a road going off to the right, keeping to the right bank of the river, which we crossed to the left. We were told that this was the road to Litang, which is only 4 days journey away. Now that we have left the Litang Road, we go more directly in the direction of Kanze. It is interesting to note that the La Ma Ya River at whose source they are now at, enters the Yangtze at about the level of Atentze. The source of the river has not hitherto been mapped, and we are now in country which no European had previously traversed”.

“The boy has just come to say that the “Big Lama” is coming along the road, and will probably call on us. I hope he may give us some information about the Kanze road. We are all glad of a short stage and a day's rest today”.

Day eighty-seven October 11th 1923 Shara-chu valley to Rei Mu Chu - 14¼ miles

“Although there was a bad frost in the morning, at 10:30 a.m. it was quite hot in the sun. The “old boy” did not come.” maybe “He copied the Priests and the Levites and passed us by on the other side”.

“We started out at about 8 a.m. following for about half an hour yesterday’s river, which turned out not to be the La Ma Ya, but one of the other sources of the Litang River. After half an hour we crossed a low spur of Hill and found ourselves on a great plateau, with low hills covered with a coarse grass; higher up was limestone rock, and away to the west a snow-peak called Dun Sha. After crossing the plateau, we descended a little (perhaps 100 ft).

In the grassy Monia plateau three streams, - the Monia Chu from the north-west, the Reimu Chu from the north, and the Sara Chu from the south-west - united to form the Li Chu, or Litang (Lijiang), which flows for 300 miles to its junction with the Yalung (Yulong), a tributary of the Yangtze.

The Monia plateau and the Litang (or Li chu) river

The Monia plateau and the Litang (or Li chu) river

"The Monia plateau is about 8 miles across each way; on the higher grassy slopes were herds of gazelle. GP had 3 shots at the gazelle, but they were a long way off, and he had no success. On the lower parts of the plateau near the small rivers were numerous black tents and thousands of sheep and yaks. In one encampment alone we counted twenty-seven tents. Numerous small streams had to be crossed, they were pouring the water into the Monia Chu river. This with the Sara Chiu River later joined the Litang River”.

In his journal HGT noted

“I’ve come to the conclusion that the River which we labelled the Ding River is really the La Ma Ya River and what we called the La Ma Ya River is the Sara Chiu, a tributary of the Litang. Where the Ding River is to be found, I cannot say, but I believe the above is correct, and probably the Ding River does not take its source till further South.”

However, GP didn’t agree. He believed that what they labelled as the Ding River was the Ding River, that they had not seen the La Ma Ya and what they called the La Ma Ya was the Sara Chiu – a tributary of the Litang (or Lijiang) River.

Sara-chiu river depression going to join Litang river

Sara-chiu river depression going to join Litang river

Sketchmap showing the campsites between 9th and 11th October as they crossed the confluence of the two rivers

Sketchmap showing the campsites between 9th and 11th October as they crossed the confluence of the two rivers

As they crossed the plateau, they saw the Sara Chiu River depression on the far side at the foot of the hills, which joined the foothills of the great range of limestone crags, forming the left bank of the Litang (Lijiang) River lower down.

“On these low hills there is a great herd of yak and nomad encampments. In one, I counted 27 tents, and there must have been about 700 or 800 yak in the one camp. After crossing the Li-Chu River 25 yards wide and 1 foot deep, we emerged on to the Mo-nia plateau. Here, the muleteers (whose home is in this valley) changed 3 yak. Then we crossed a low hill and entered the small valley of the Rei Mu Chiu river”.

“The valley is a great grazing ground and just covered with beautiful white sheep, and in another group hundreds of black yak. It is wonderful how these animals keep in their own groups. A covey of 6 or 7 partridges rose just before us and crossed the little river onto the hillside beyond, but there were so many sheep and yak about that the shot would have been risky, also the Tibetan boy advised against shooting, as there are many Tibetan herdsman about, and the Tibetans object to the taking of life”.

They continued up the Rei Mu Chu Valley (13,790 ft.) till the sheep and yak were left behind, and they then pitched camp on a piece of fairly level ground close to the stream. It was very cold and as they crossed the plateau, they were glad of their fur coats, as a bitter wind was blowing from the snowy mountains.

In his letter home HGT said

“Yesterday, we bought a sheep for 4 shillings, so we are going to have liver and bacon for supper. The bacon came from Mr. MacLeod, his own curing”.

“The Monia plateau and the valley of the Litang (Lijiang) river is the main centre of the Monia section of the Washi. Unfortunately, we did not get to see the Queen of the Washi tribe, as she is ½ day’s march down the Mao Neob Valley and we could not spare the time”.

“We pushed on due north up the valley of the Rei mu chu till we camped at the foot of the pass called Rambu La. It is a barren spot and bitterly cold. Besides the eiderdown I had two thicknesses of Jaeger sleeping bag, a blanket, the fur lining of my Burberry, 2 pairs of socks and a vest, and one shirt under my pyjamas; in this way I got warm. Just as we were turning in we heard a gentle patter on the tent, and found it was snowing hard and blowing from the north. During the night the front of our flimsy tent collapsed with the weight of snow and the wind. It was fixed up somehow by the boys, and soon morning dawned”.

Day eighty-eight October 12th 1923 Rei Mu Chu to Ta Chi La valley - 13¾ miles

“The morning dawned cold and inclined to snow. We started at 7.30 and continued up the Rei Mu Chu Valley, a long steep climb, till at last we crossed the pass at the top called the Rambu la, (14,400 ft. approx) 3¼ miles from our start. This is the divide between the Li Chu and the Ho Chu. Here there is a most wonderful view – looking back, we can see range upon range, and in the far distance the Pik Des Gaudins. Looking forwards there is a valley with hills surrounding it covered with snow, and a river flowing at the bottom, called the Guo chen chu (13,600 ft.)- a tributary of the Ho Chu”.

Looking north from Rambu-la

Looking north from Rambu-la

Before going down GP asked HGT to take the boiling point in order to get the height. HGT records in his journal:

“Unfortunately, yesterday, our last bottle of methylated spirits got broken by the yak carrying the load frisking about. So, I filled up the lamp with brandy. I tried for nearly half an hour and could not make it burn, then we tried a little fire with matches – no use – then I took some fur from my fur coat, soaked it in brandy – no use! So, we had to guess the height and get on our journey.”

They descended into a narrow grass valley between bare grass hills. At 6½ miles the Guo-chen Chu, was forded. Here there were the usual tents and barking dogs. They were the only nomads seen during the day and they belonged to the Dei-yung tribe of the Wa-shi.

“After crossing the tributary of the Ho Chiu, we began the ascent of another valley. At the top another pass, the Bei Lung La (about 14,800 ft.) (10 miles from the start). This is a very narrow pass. Looking from the top there is an amphitheatre of hills with a stream running out at the Eastern side, and a huge limestone crag in front. All the hills are practically covered in snow, and it is magnificent”.

Looking north from Bei Lung La valley

Looking north from Bei Lung La valley

“We could see another ridge in front with a pass called the Ta Chi La also (about 14,800 ft.). We skirted round the amphitheatre of hills and crossed the pass. In front is a great valley with a stream running North, and beyond there are low hills forming the boundary of a far distant valley, which is evidently the Valley of the Ho Chu. Beyond this was a range of mountains, the divide between Ho Chiu and the Ya Lung – which we will have to cross before we reached Kanze. On the left, great mountain ranges, evidently bounding the Yangtze”.

“It is all so beautiful, but snow keeps falling and it is very windy (a Northwind - very bitter). We descended into the Ta Chi valley and then set up camp on a ledge on the west slope. It was snowing a little as we arrived, though the sun has been shining. We got our tents up, had a hot lunch and later dinner, and then turned into bed”.

Looking south towards Ta-chi-la in Washi country

Looking south towards Ta-chi-la in Washi country

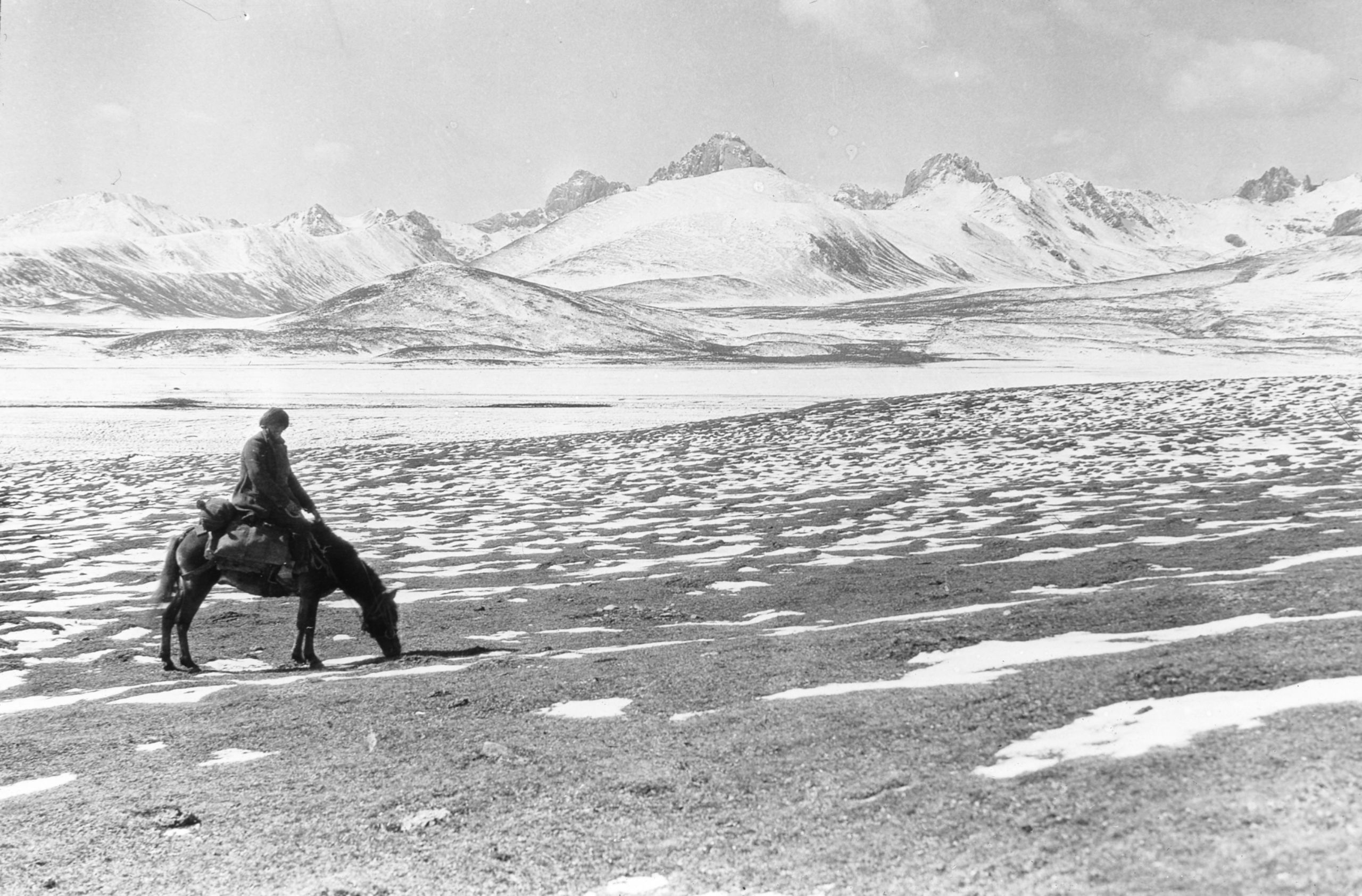

GP and Yaks coming through snow

GP and Yaks coming through snow

“Between the two passes GP’s pony went lame and something went wrong with his compass. However, one of the Tibetans has let him have his pony and I supplied him with a prismatic compass, and so we managed to keep going and keep our records. I spent an hour or two fixing up the hypsometer to work with a candle instead of methylated spirit, and found that the boiling-point gives the altitude of their camp as 14,470 ft. It is a bitterly cold night, snow and a strong north wind, hardly any fuel to be obtained and GP beginning to feel distinctly unwell”.

Day eighty-nine October 13th 1923 Ta Chi La valley to Jou Ri Ku - 15 miles

“Another day's journey over. It has been a bitterly cold night, snow, and towards early morning so strong a North wind that we both thought the tent would be blown down. However, all stood firm, except one peg. We are on a very exposed place on the mountain side”.

“We had breakfast at 6.45, but did not get off till 8 a.m. Oh! it was cold! But with both the fur waistcoat and coat I was able to keep warm”.

They continued down the valley, crossed a small river, evidently a tributary of the Ho Chiu and then crossed a great open valley - there was about 2 inches of snow in the hollows, and the hills and mountains were covered, mostly on the windy side. They crossed a pass called the Hara gu-lu 5¼ miles from start, not very high, but about 14,400 ft. and then descended a few hundred feet down a valley into a big open plain, surrounded by mountains - except at a gap at the North side. This was the Tze-ku Chu valley, about 2 miles wide and 7 miles long from the place where they entered it. The road ran mostly along the West side, but occasionally out across a piece of the plain. The river ran southward, evidently going to join the Ho Chiu.

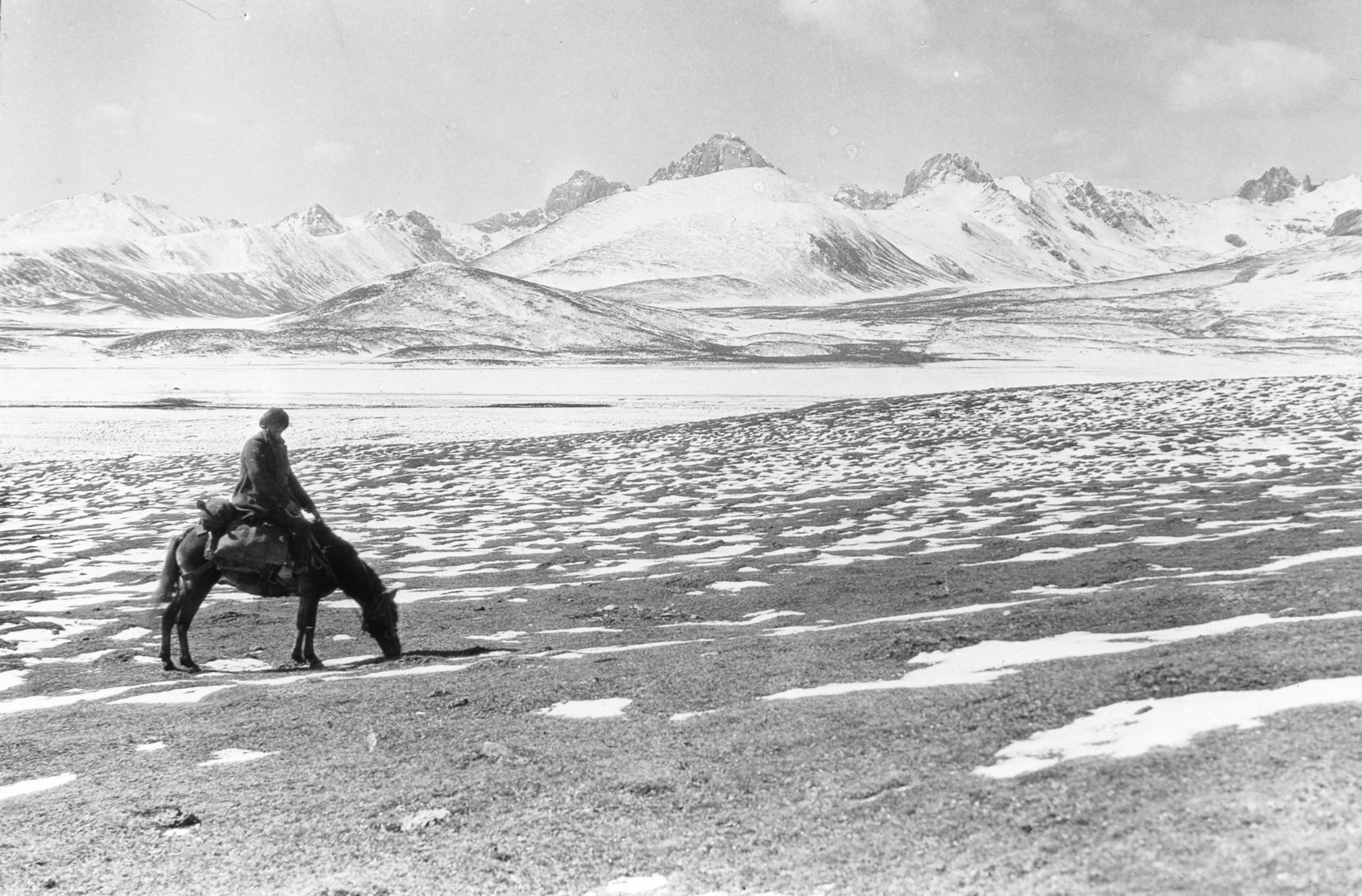

“The place is one large grassy, peaty surface, with pools in between, and we have to guide the ponies carefully, for a false step would land them up to their chests in black mud. It was a long track without a sign of life, except a few gazelle in one herd on the hillside; at which one of the Tibetans had an unsuccessful shot. The General had lent him his rifle, which the boy was carrying, and in passing it over, the boy's pony was startled and bolted, tossed the boy off and dislodged the saddle. However, he was soon caught and the boy was none the worse; neither were the gazelle!”

Camping at Jou Ri ku in the Washi country

Camping at Jou Ri ku in the Washi country

Following this was a gradual rise. At the end after 13½ miles they crossed a low pass, the Crei tay Nya-ra (Nya-ra or Ya-k’ou means pass) (14,000 ft.), and another mile and a half down a steep valley descent with a river flowing North brought them to their camp Jou Ri ku (13,563 ft.). They were about l,000 ft. lower than the previous night and although they had had more snow it was much warmer as they were in a cosy corner, protected from the wind. No human had been seen all day, but there was a small stone chorten just opposite the camp, to take care of them!

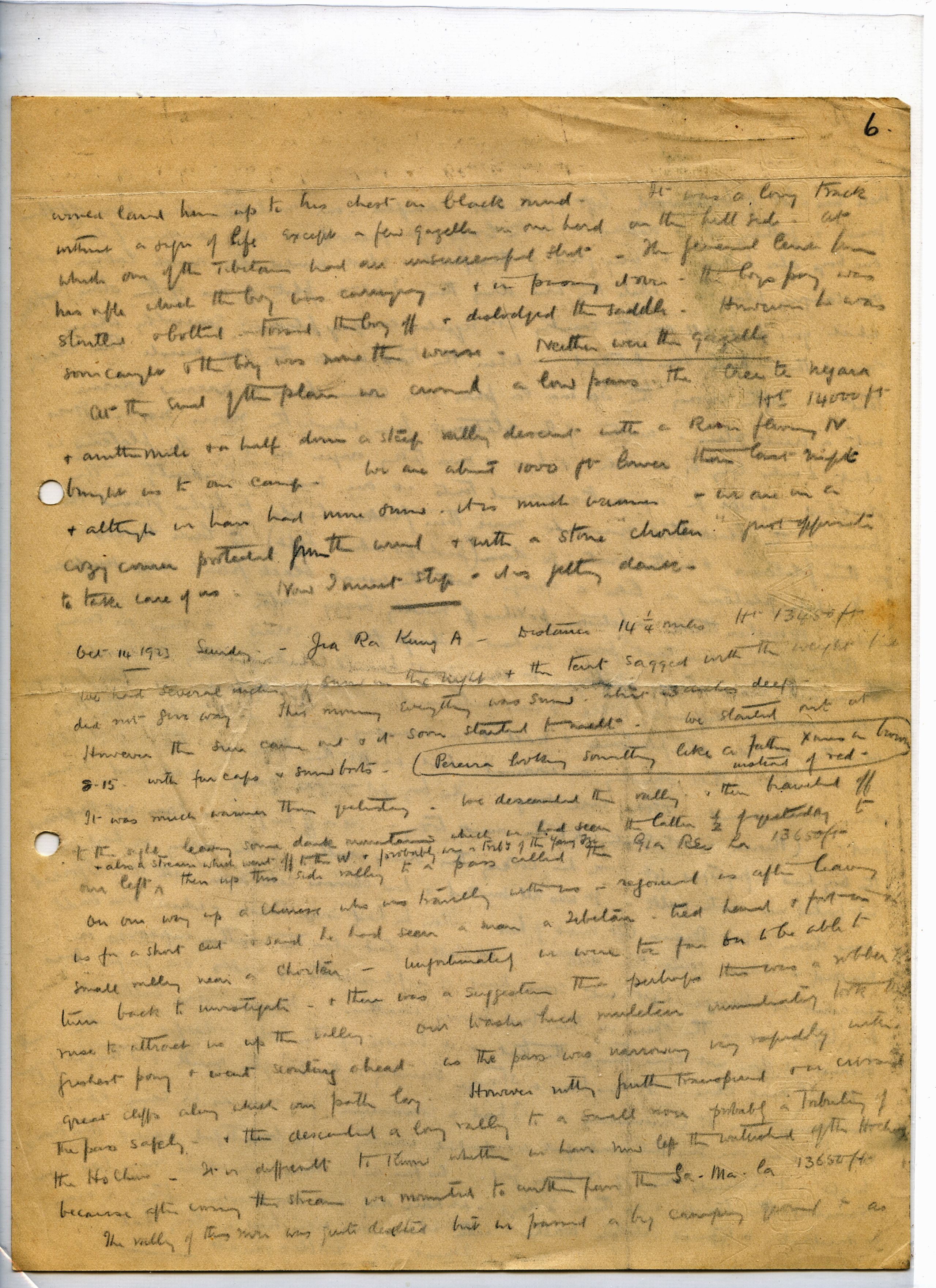

Excerpt from his journal that HGT copied and sent as a letter home

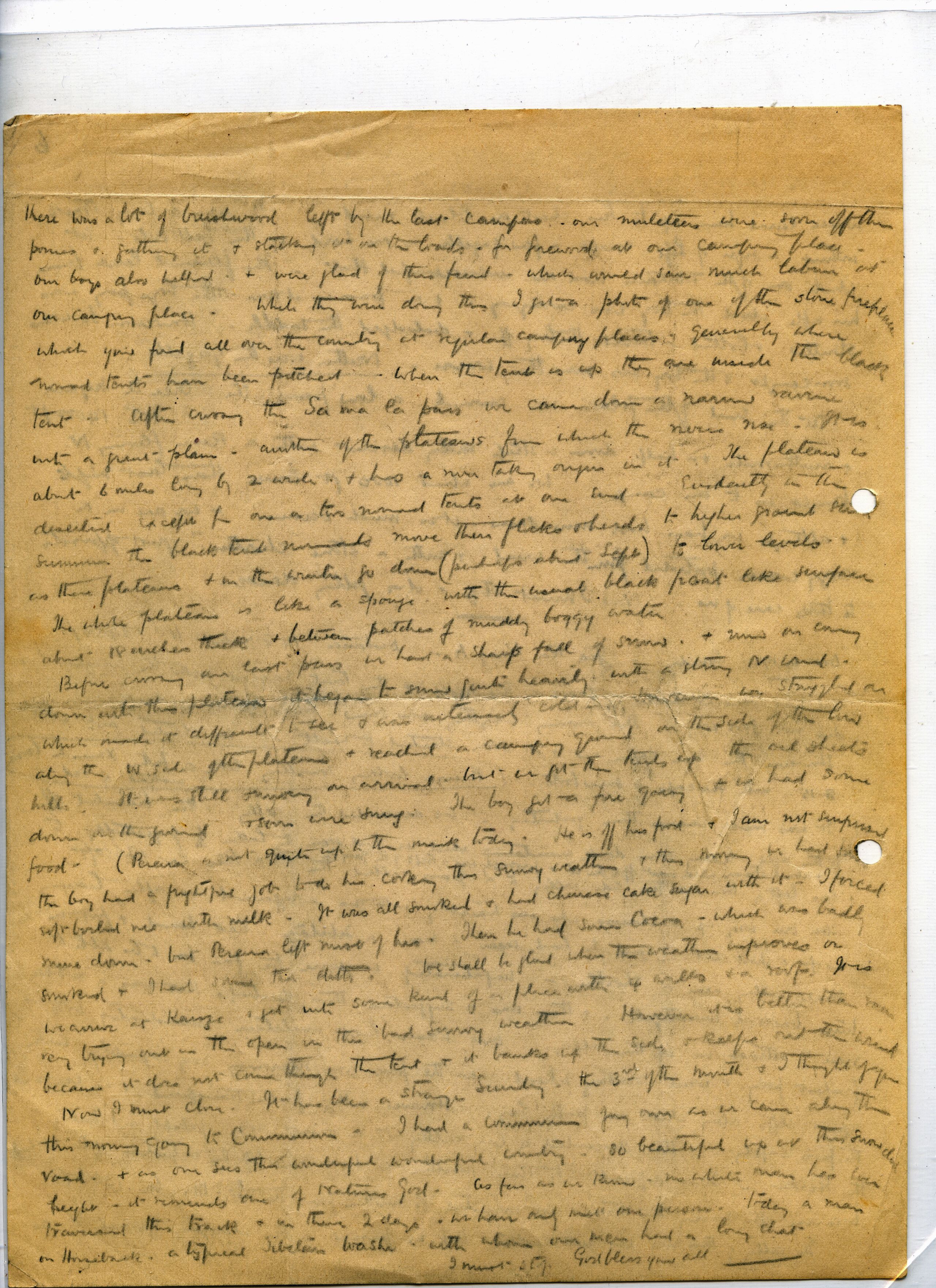

Day ninety Sunday October 14th 1923 Jou Ri Ku to Jia Ra Kunga - 14¼ miles

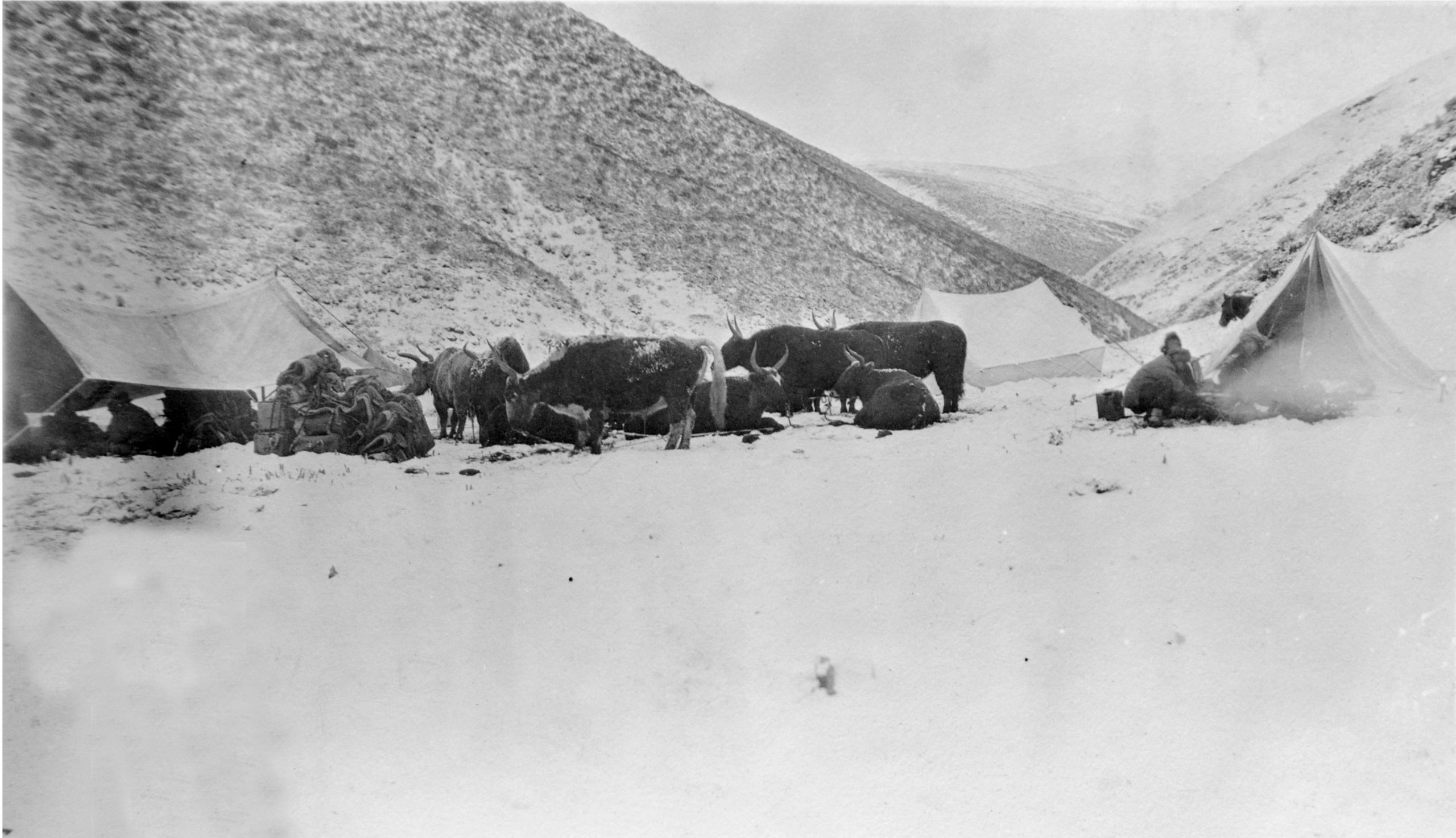

We had several inches of snow in the night and the tent sagged with the weight, but did not give way. This morning everything was snow - about 3 inches deep. However, the sun came out and it soon started to melt. We started out at 8.15 with fur cap and snow boots - Pereira looking something like a Father Xmas in brown instead of red. It was much warmer than yesterday. We descended the valley and then branched off to the right, leaving some dark mountains which we had seen the latter half of yesterday to our left, and also a stream which went off to the West, and probably was a tributary of the Yangtze.

Then up this side valley to a pass called the Gsa Rei la, 13650 ft. On our way up, a Chinese who was travelling with us rejoined us after leaving us for a short cut, said he had seen a man, a Tibetan, tied hand and feet in a small valley near a chorten. Unfortunately we were too far on to be able to turn back to investigate, and there was a suggestion that perhaps this was a robber's ruse to attack us up the valley. Our Washi head muleteer immediately took the fastest pony and went scouting ahead as the pass was narrowing very rapidly, with great cliffs along which our path lay. However, nothing further transpired and we crossed the pass safely and descended a long valley to a small river, probably a tributary of the Ho Chiu. It is difficult to know whether we have now left the watershed of the Ho Chiu, because after crossing a stream we mounted to another pass, the Sa Ma La, 13750 ft.

The valley of this river was quite deserted, but we passed a big camping ground and as there was a lot of brushwood left by the last campers our muleteers were soon off their ponies and gathering it and stacking it on the loads for firewood at our camping place. Our boys also helped and were glad of this find, which would save much labour at our camping place. While they were doing this I got a photo of one of the stone fireplaces which you find all over the country, at regular camping places, generally where nomad tents have been pitched. When the tent is up they are inside the black tent. After crossing the Sa- ma-la pass, we came down a narrow ravine into a great plain, another of the plateaus from which the rivers rise. It is about 6 miles long by 2 wide and has a river taking origin in it. The plateau is deserted except for one or two nomad tents at one end. Evidently in the summer the black tent nomads move their flock and herd to higher ground, such as the plateau and in the winter go down, (Perhaps about September) to lower levels.

The whole plateau is like a sponge with the usual black peat like surface about 15 inches thick, and between, patches of muddy boggy water.

Before crossing our last pass we had a sharp fall of snow, and now, on coming down into this plateau, it began to snow quite heavily, with a stormy North wind which made it difficult to see, and was intensely cold. However, we struggled on along the West side and reached the camping ground on the side of the low hills. It was still snowing on arrival, but we got the tents up and oil sheets down on the ground, and soon were snug. The boy got a fire going and we had some food (Pereira is not quite up to the mark today - he is off his food, and I am not surprised, the boy had a frightful job to do his cooking this snowy weather , and this morning he had some soft boiled rice with milk. It was all smoked and had Chinese cake sugar on it. I forced mine down but Pereira left most of his. Then we had some cocoa, which was badly smoked, and I had some .......... We shall be glad when the weather improves, or to arrive at Kanze to get into some kind of place with 4 walls and roof. It is very trying out in the open in the bad snowy weather. However, it is better than rain because it does not come through the tent, and it banks up the sides and keeps out the wind.

Now I must close. It has been a strange Sunday, the third of the month, and I thought of you this morning going to Communion. I had a communion of my own as we came along this road, and as one sees the wonderful, wonderful country - so beautiful up at this snow-clad height, it reminds one of Nature's God. As far as we know no white man has ever traversed this track, and in these two days we have only met one person. Today a man on horseback, a typical Tibetan Washi, with whom our men had a long chat. I must stop.

God bless you all.

Day ninety Sunday October 14th 1923 Jou Ri Ku to Jia Ra Kunga - 14¼ miles

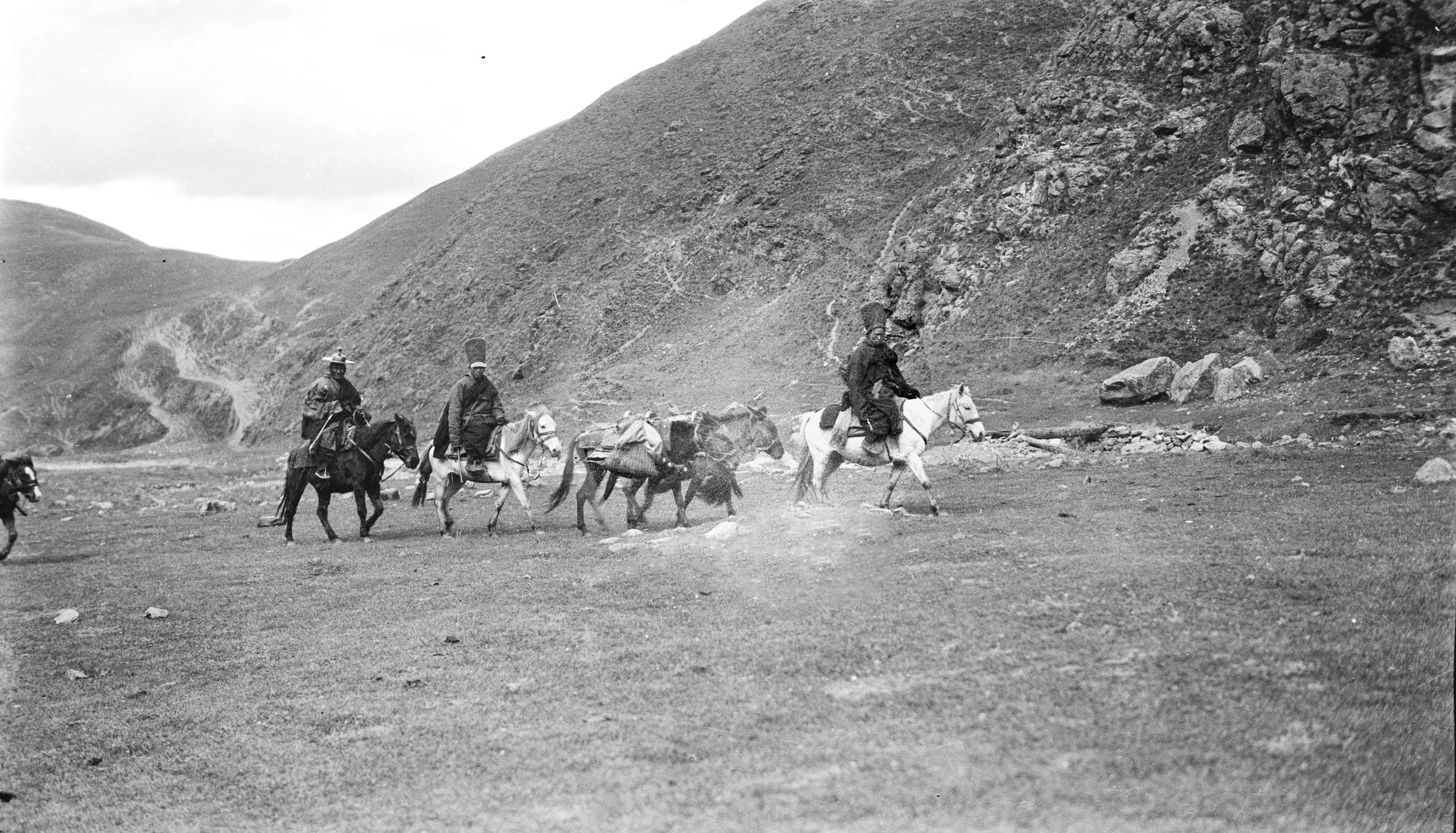

GP and caravan trekking through Washi country

GP and caravan trekking through Washi country

“We started out at 8.15 with fur cap and snow boots – GP looking something like a Father Xmas in brown instead of red. It was much warmer than the previous day. We descended the valley and then branched off to the right, leaving behind some dark mountains to our left, and also a stream which went off to the West, and probably was a tributary of the Yangtze”.

“The valley of this river was quite deserted. We passed a big camping ground where there was a lot of brushwood left by the last campers. The muleteers were soon off their ponies and gathering it and stacking it on the loads for firewood at their camping place. The boys also helped and were glad of this find, which would save much labour at our eventual camping place. While they were doing this, I got a photo of one of the stone fireplaces which we have found all over the country, at regular camping places, generally where nomad tents have been pitched. When the tent is up, the fireplaces would be inside the black tent”.

A Tibetan camp fireplace - hearth and home

A Tibetan camp fireplace - hearth and home

“After crossing the Sa- ma-la pass, we descended a narrow ravine into a great plain (debouching); another plateau from which the rivers rose. It was about 6 miles long by 2 wide and had a river taking origin in it. The plateau was deserted except for one or two nomad tents at one end. Evidently in summer the black tent nomads move their flock and herd to higher ground, such as the plateau and in the winter (about September) they go down to lower levels”.

Debouching onto the Jia-Ra-Kunga plateau

Debouching onto the Jia-Ra-Kunga plateau

The whole plateau was like a sponge with the usual black peat like surface about 15 inches thick, and between, patches of muddy boggy water.

Before crossing their last pass there was a sharp fall of snow, and then, on coming down onto the plateau, it began to snow quite heavily, with a stormy North wind which made it difficult to see, and was intensely cold. However, they struggled on along the West side and reached the camping ground on the side of the low hills. Jia Ra Kunga (13450 ft.).

“It was still snowing on arrival, but the boys got the tents up and oil sheets down on the ground, and soon we were snug. The boy got a fire going and we had some food. Pereira is not quite up to the mark today - he is off his food, and I am not surprised, the boy had a frightful job to do his cooking this snowy weather, and this morning he had some soft-boiled rice with milk. It was all smoked and had Chinese cake sugar on it. I forced mine down but Pereira left most of his. Then we had some cocoa, which was badly smoked, and some tinned stores. We shall be glad when the weather improves, or to arrive at Kanze to get into some kind of place with 4 walls and roof. It is very trying being out in the open in the bad snowy weather. However, it is better than rain because it does not come through the tent, and it banks up the sides and keeps out the wind.”

In spite, of his sickness GP still kept up his detailed description of each day's march. In his journal GP said:

“Prospects very wretched, besides I had nausea and indigestion, and the sight of my boy's food made me feel sick”.

Day ninety-one October 15th 1923 Jia Ra Kunga to Chao Lung - 8¾ miles

“I had a very trying night. It snowed and froze hard during the night. There was something wrong with my bedding and I could not get really warm. I did get some sleep, but was very glad when daylight came. The roof of the tent was like a sheet of ice and the ground was damp and very cold. However, the ground sheet had kept it from striking up too badly. Soon the sun came out and things warmed up”.

“We struck camp in 2 to 3 inches of snow, but the sun was shining and made things cheerful. At 8 a.m. we were under way; leaving the plain referred to above, by crossing a shoulder of hill and then entering a valley bearing to the North. After a steady but gradual descent we came in sight of two chorten which were at the entrance to a good-sized plain about 5 miles by 2 miles wide, with a lot of yak and sheep, also tents in the distance and a river running through it”.

“When we reached the chorten we crossed the stream we have been following and began to ascend in a Westerly direction. Passing a spar of hill, we entered another valley and going steadily up eventually reached a small pass at the top called the Chao lung la. We descended the other side, passing a nomad camp of about 6 tents, where the dogs were very fierce. Finally, we camped in the Chao Lung valley (12,885 ft). This was the lowest we had camped since the day after leaving Batang, 10 days before. The weather seems to be on the mend and I was able to sit in the tent without my fur coat. We did have a shower of hail, like snow, but it was quite mild compared to what we have had. This was the day we left the Washi country at the Jara-güng plain and entered the Nyarong (or Chantui) nomads’ territory”.

“The other night a yak got loose from his tether and came munching the grass close to our tent and bumping into the rope. We expected the tent might go over, but the Tibetan muleteer got him before he had done much damage. Yesterday the muleteers lost their way, but today we have seen quite a number of people, and we are apparently on the right track again. They say we shall be in Kanze in two days, but Pereira reckons about 5. It will be interesting to see who is right. I hope the muleteers are!!”

“GP was not well, though an attack of vomiting seemed to give him relief, and some bismuth and other drugs I administered seemed to ease him slightly”.

Sketch map of the 2nd stage from Chao Lung Camp to Kanze - 61½ miles

Sketch map of the 2nd stage from Chao Lung Camp to Kanze - 61½ miles

Day ninety-two October 16th 1923 Chao Lung to Chu Gu Chu - 13½ miles

Encamped by lake

“Last night we had just turned in, GP was asleep and I was reading, it was only about 7.45, when suddenly it began to blow hard and I really thought the tent would either be blown away or be torn from its stay ropes. The Tibetan boy drove in the tent pegs. Then it began to rain and this turned to snow. However, the wind dropped and we had a good night. In the morning there was 2 inches of snow”.

“However, we were up betimes (in good time) - struck camp and started out at 7.30. Heavy clouds everywhere make it look like more snow. During the night the muleteers told the boys that there was a band of 40 or 50 robbers in the country between us and Kanze and that two days before they had stolen a dozen horses. GP asked if they could go by any other road and miss them, but they said there was no other road. One of the drivers had got the news when he went out to try to get a guide for the rest of the journey”.

“We discussed what we should do. I thought it was best to go straight on through and not delay, so that we might be ahead of our own news.

“We learnt that with so few people on the road, the bands of robbers do not wait specially by the road, but move about. We decided to carry our arms and go ahead. The muleteers seemed to think it was very important to push ahead, now that they were only 2 or 3 days from Kanze. It seemed more risky to turn back than to go on. (See Daily Light for yesterday October 15th).

They pushed on and marched 13½ miles to Nan-lung Tsa camp. All day the road lay up and down over high grass downs with streams flowing south-west, presumably into the Yangtze. They forded the two branches of the Druga Chu, a large river flowing West, then climbed the Dru La hills at 3¼ miles, and then down into more open country.

“We entered a valley where there were lots of hares which bolted at our approach. At one end of the valley was a small lake called Nam Loong, about 1 mile long by ¾ mile wide, very pretty and almost like Lake Louise in the Rockies”.

Valley of Chu-gu-chu

Valley of Chu-gu-chu

“After fording the Tsai-mo Chu, we climbed over another shoulder of hills called the Tsai mo La (13,500 ft.), at 9½ miles. We crossed the low pass and then descended into another nice grassy valley, where the Chu-gu Chu river flows West South West. We forded the river and followed it Eastwards to our camping ground by a second lake”.

Making camp by lake of Na-lu-tso

Making camp by lake of Na-lu-tso

“The lake was about 2¼ miles long by 1 mile wide. It was quite pretty, but not so picturesque as the Nam Loong lake. Unfortunately, the concern about bands of robbers made us all keep together and I was not able to get a photo of the Nam Loong lake, as it was about 3/4 of a mile from the road. But I did get a photo of the lake where we camped. It is called Na Lu Tso (13,111 ft.).

Na Lu Tso lake

Na Lu Tso lake

“Both of these lakes empty their waters into rivers going West, evidently to the Yangtze, so now we are on the Yangtze side of the Ya Lung-Yangtze divide. Tomorrow we expect to ascend the river that feeds the lake, cross the divide at a pass and begin to descend to the river Ya Lung. If our guide is right, we hope to get to Kanze in two days”.

“GP seems a little better but he is not right yet. I think he must have caught a chill. He is living on milk, Bovril, cornflour and dry biscuits. We recognise it will be good to get to Kanze, where we can have a day or two’s rest, in a house instead of a tent”.

Day ninety-three October 17th 1923 Chu Gu Chu to Lung Ni - 16 miles

"It was a glorious morning as we got the camp broken up and got under way. The lake looking so beautiful, but it was too cold for a dip - icy cold. No snow last night, only a sharp frost”.

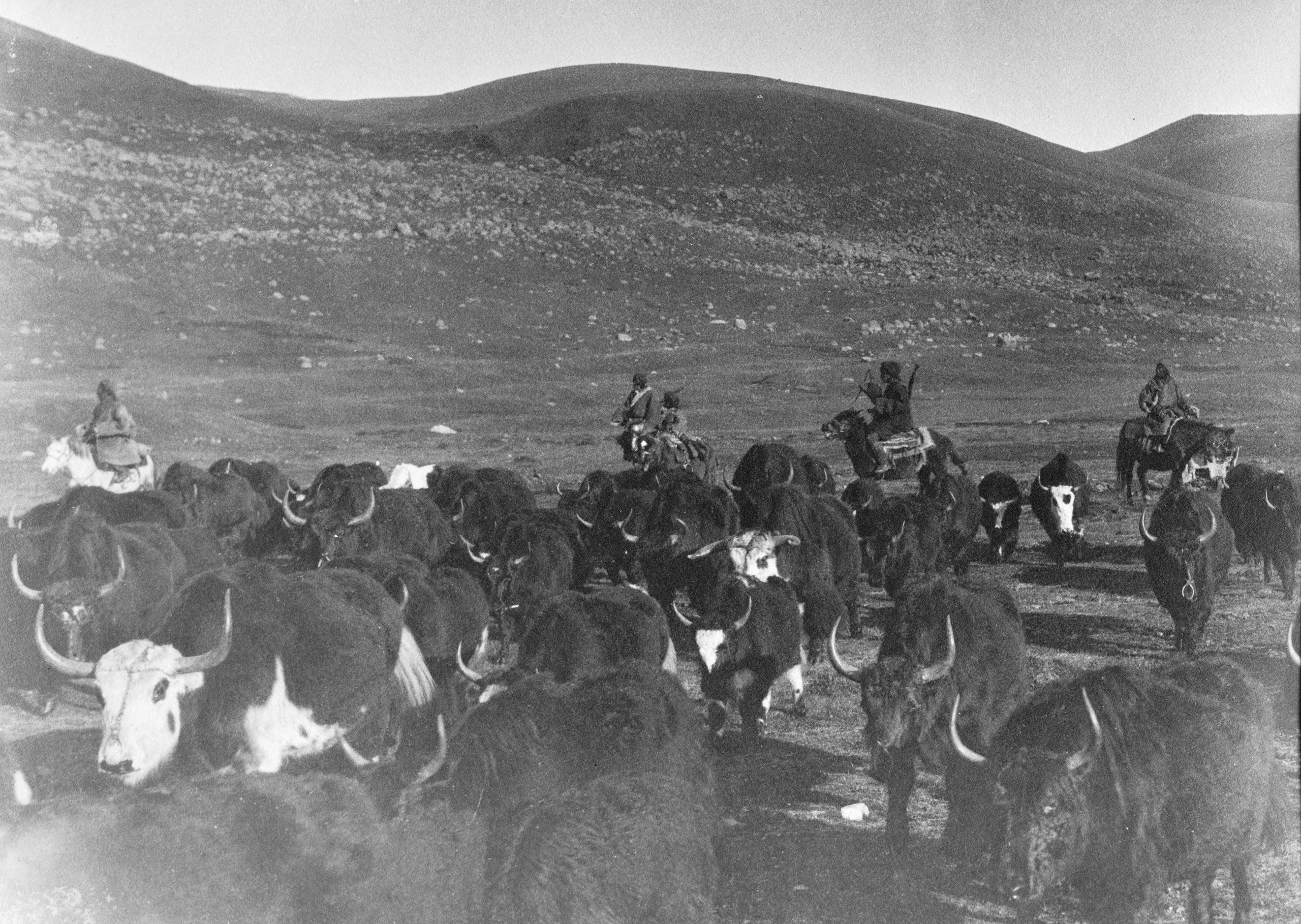

They were just leaving at 7.30 when a great herd of about one thousand yak with, as they thought, Nyarong tribesmen went past. They told GP that they were Jyade and not Nyarong people They were changing their grazing-ground.

“A young girl with her hair done in numerous plaits woven into round silver plate-like ornaments, with her brightly coloured high-top boots and sheepskin coat and cap, made a picturesque figure as she rode at the rear of the herd. I got a couple of snapshots - one in the middle of the yak - the other of GP having a chat with some of these people. They gave us good news that there is nothing to fear on the road”.

Jyade tribes’ people moving camp

Jyade tribes’ people moving camp

Enquiring the way. Young Jyade Washi woman (in the foreground)

Enquiring the way. Young Jyade Washi woman (in the foreground)

“We set off immediately after the herd had gone by. We skirted the west bank of the lake and then continued up the valley- going North, up and up, and up, until after 2¾ miles at about 11.30 a.m., we reached the pass at the top called Momu Nya-ra (or maybe Ngo Mi Kyana) 14,244 feet. This pass is the divide between the Tang-ho and the Ya Lung watersheds. On the top are great rolling plateaus and lying in front of us a range of snow peaks - which lie closest to the Ya Lung river.

“Here we wanted to check the height by the boiling point. Having no methylated spirits we are managing with a bit of candle and just at the critical moment the candle went out. I had a spare piece in my pocket and after some delay got it going. Then this was melted by the hot brass case and out it went, so we soaked a bit of cotton wool in the hot grease, set a light to it and at last got the boiling point, and the height 14,244 ft”.

“Meanwhile the caravan had gone on and was out of sight. However, the boy and I followed the tracks of the yak and at last caught them up”.

Looking down the valley from the Dumbola pass - Note the caravan in the mid-foreground

Looking down the valley from the Dumbola pass - Note the caravan in the mid-foreground

Dum bo la mountains nearing Kanze

Dum bo la mountains nearing Kanze

Another view of the Dum bo la mountains nearing Kanze

Another view of the Dum bo la mountains nearing Kanze

“The road descended and we crossed a great, slightly undulating, very stony plateau extending some 15 or 20 miles to the north-west and north. The path then descended further to a small lake 200 yards wide and 2 feet deep. Beyond this was a descent through an open rocky valley and after 11¼ miles we reached our camping place Lung Ni (13,790 ft.). I carried on to the top of a ridge, 1¼ miles away, to get a better photo of the big Dumbola mountains”.

“Approaching this range from the south, one rocky peak called Nashi or Dumbola was covered with snow, but it was so perpendicular that the rocky face could be plainly seen. It reminded me of the design for the new Liverpool Cathedral, for the peak rose in the centre of other rocky crags like the huge cathedral tower that will soon be seen at Liverpool”.

Dum-bo-la mountain from the top of the pass

Dum-bo-la mountain from the top of the pass

“When I got there, I pegged the pony with a rope, which the Tibetans always carry attached to a halter and sling on the saddle. Then I climbed up on a rock to get a photo. I had taken the thermos flask out of the saddle bag in case the pony rolled, and on my return, I found the pony had got loose. He had pulled the peg out and was trotting quietly back to camp. I tried to catch him but it was of no use and I was too tired. So, I had to trudge back to the camp carrying the camera, stand and thermos etc., while the pony nibbled grass and trotted on in front, just out of reach”.

In his letter home, HGT said:

“Pereira seems a little better tonight, but not right yet. We cannot reach Kanze tomorrow - they say it is a day and a half's journey from here. However, although tonight we are higher than last night, we are on the down gradient. I hope tomorrow night we shall be nearer 12,000 ft. than 13,000 ft. (tonight we are 13,790) then it will be warmer. I must stop now as it is getting dark. Good night”.

Day ninety-four October 18th 1923 Lung Hi to Raji-sumdo - 17 miles

“We set off at 7.15 a.m., following the stream by which we had camped, in the direction of the Dumbola Mountains. Unfortunately, at the start of the journey the upper 2/3rds was enveloped in mist. The way led down valleys for 8½ miles. When we neared the valley, which evidently had a river into which the stream emptied itself – we turned to the left round a hill and still going on down came to the river we had expected, viz., the Ho Chu (Asei-Yindu Chu). We crossed this at a ford which was 15 yards wide and 1 foot deep”.

Their way then lay up a narrow valley, round the side of the Dumbola, up through quite a narrow defile - resting the ponies every few minutes as they got nearer the top. This was evidently the dividing range between the Ho Chu and the Yalung River.

“At last we reached the snow line. The path up the hillside turned sharply to the left and we saw above us the usual pile of stones with prayer flags, which marks the highest point of the pass called the Lu Mu la. We took the boiling point and noted the height was 15,152 ft. The elevation of Ho Chu river was 12,000 ft. so we have just climbed about 3,000 ft.”

Dum-bo-la mountains with Ho chu river in the foreground

Dum-bo-la mountains with Ho chu river in the foreground

“There was a magnificent view from the top of the pass, up the side of Dumbola. The top of the pass was only about 3,000 ft. from the summit of the mountain. It was beautifully clear. I took some photos in 6 inches of snow!”.

HGT and ponies at the top of the ridge

HGT and ponies at the top of the ridge

“GP had ridden his pony nearly all the way, but the last 200 feet of the pass was in such deep snow that he had to get off and do it on foot. He seems in good spirits, for this was, he was sure, the last high pass. As he went by me, he called out to say how much better he feels this morning”.

“After taking the photographs, I followed GP down the valley, a little to the east of north. The journey down was by the side of the Yalung river until at last we camped at Rajisumdo (13,337 ft)”.

Looking up the valley to Rajisumdo camp

Looking up the valley to Rajisumdo camp

“As always each evening, GP works on his map on our arrival in camp”.

Camp at Rajisumdo - snow covered tops of Dum-bo-la mountains from the top of the pass

Camp at Rajisumdo - snow covered tops of Dum-bo-la mountains from the top of the pass

HGT’s noted in his journal:

“A great mass of grey rock towers above us, crowned with snow. The rock has great streaks of yellow in it, and is magnificent.

"Pereira seems distinctly better today, but is still not right yet. We are due to arrive at Kanze tomorrow”.

Day ninety-five October 19th 1923 Raji-sumdo to Kanze - 15 miles

They started out at 7.45 a.m. breaking camp with snow on the ground and also falling slightly.

“GP seems a little better and had his breakfast of milk and biscuit with a little jam - more than he had had for some days. I took the precaution of putting some hot chocolate in the thermos in his saddle bag, for I fear we may have a considerable delay when we reach the coracle ferry over the Yalung river, near Kanze”.

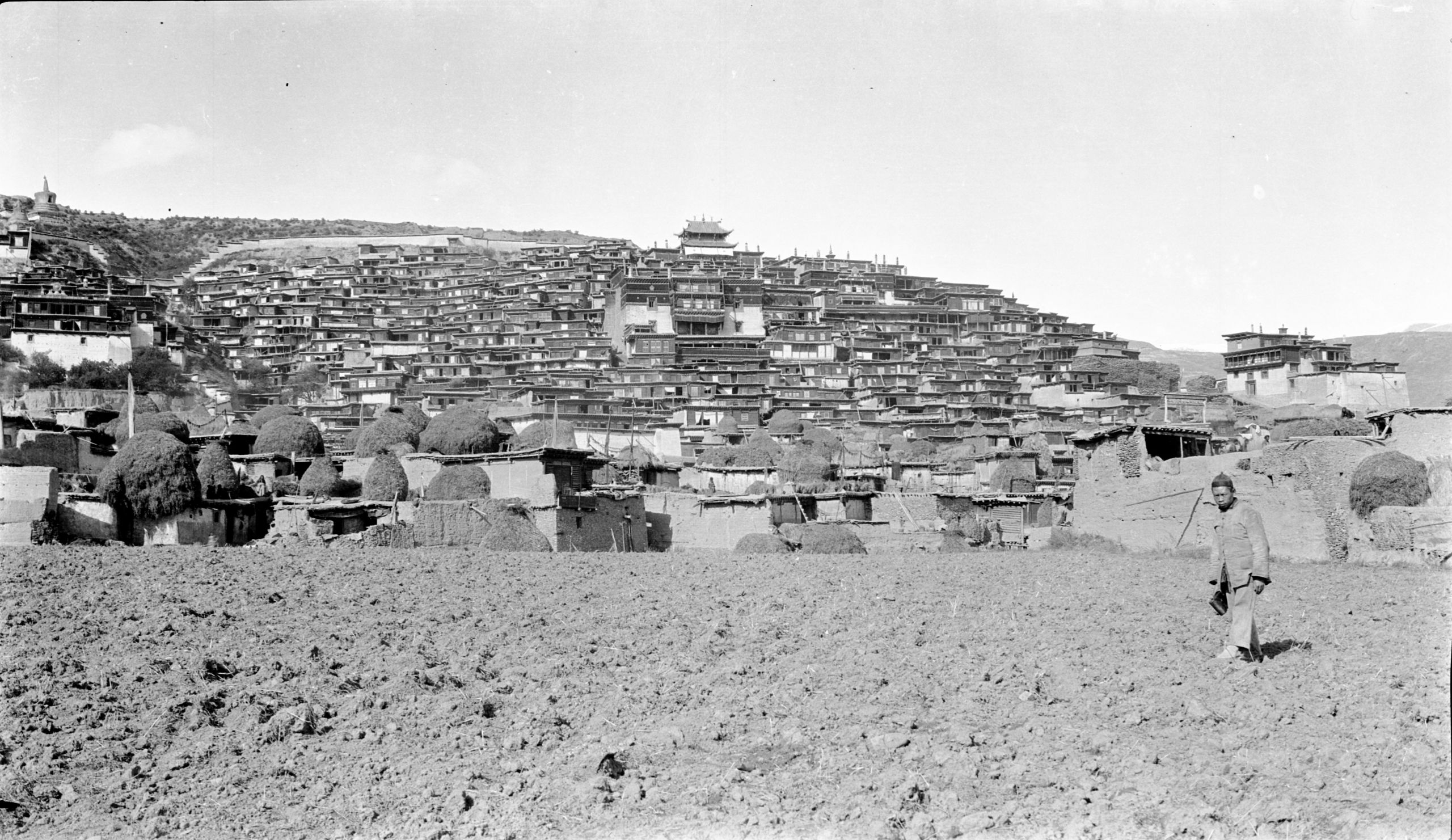

“Once again, our road lay down the valley following the stream. Soon after starting the snow stopped falling, except for occasionally a few flakes - everything was white and beautiful. We had to cross the stream twice by fords, when the track changed sides, on account of the steepness of the mountain side. At 11.30 the valley opened out and on the hill opposite was a Lamasery called Dorga Gumbo, with a peculiar lot of hovels built in mud on the side of the hill just below, looking very much like cave dwellings”.

Dorga Gomba (Lamasery) at Kanze. HGT was housed where tents are hung out (above soldier's head)

Dorga Gomba (Lamasery) at Kanze. HGT was housed where tents are hung out (above soldier's head)

“At 12.05 I was with the muleteers following the first lot of 9 yak when the Chinese merchant who was travelling with us called out to me that GP was off his pony, and he was afraid he was not well. On looking back, I saw that about a quarter of a mile back GP was on the ground - and the Tibetan boy was with him. I galloped back”.

“Just before I arrived GP got on his pony again with assistance and rode on again. He had not fallen from his horse, but was in such pain that he felt he must lie down. Fortunately, by this time we were down at 10,000 ft. altitude and there was no snow on the ground. It was quite mild”.

“I suggested a long rest and GP readily assented. We took off a saddle for a pillow, spread saddle cloths and made him comfortable. The hot chocolate was taken with difficulty. The loads went on ahead in order to get across the river which takes some time in the small coracle boats. After 50 minutes GP said he thought he could go on. I proposed staying at a farmhouse nearby, but as they were only a little over 2 miles from the Yalung river, and 3¾ miles from Kanze, GP said he felt he wanted to go on”.

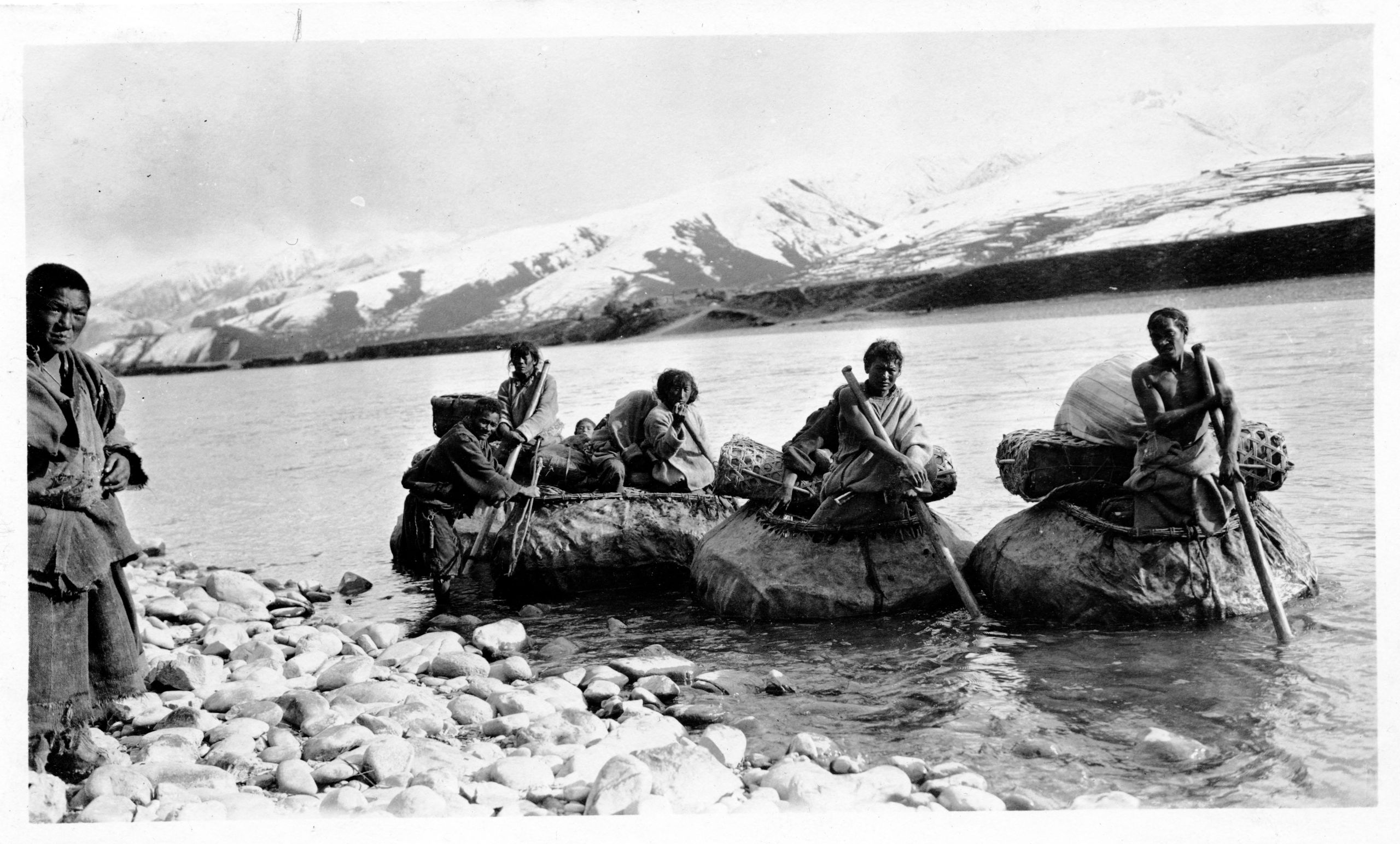

Coracle Ferry over the Yalung river at Kanze with loads going on ahead

Coracle Ferry over the Yalung river at Kanze with loads going on ahead

“So, with GP’s pony being led, we made our way down to the ferry. Here I gave him some stimulant to tide over the rest of the distance, and we got across the river in a coracle boat, having already sent the Tibetan boy on with a man who knew Kanze, taking GP's camp bed and bedding with orders to find a place to stay, and get the bed ready pending our arrival.

HGT and GP crossing the river Yalung at Ka near Kanze by coracle

HGT and GP crossing the river Yalung at Ka near Kanze by coracle

“Having crossed the river, GP seemed very weak, so we hastily fixed up a camp bed and bedding and put him on to it. The abdominal pain slowly passed off. We tried to get some passing Tibetans or their own Washi yak drivers to carry the bed, but no one would consent to do so at any price. With only 1¾ miles to go GP thought he could manage on the pony. As time was getting on it would soon be dark. I adopted his proposal and got him on to the pony. The boy walked by his side, holding his clothing to steady him. Half way we had a 10 minute stop to rest. Then we set off again, and at 5.20 we arrived at our destination, Kanze (10,755 ft.)”.

“When we arrived, the bed was all ready and GP was soon undressed and in bed with hot water bottles. The pain in his abdomen and between his shoulder blades was very severe and he begged for a sedative. After trying various things, and getting him to take hot milk, I gave him a hypodermic. This eased the pain. He was very grateful. At a quarter to 9 he asked for the light to be put out and he would try to sleep, but he was very restless and moaning in a dull way. At 10.30 he asked for a drink of cold water. This I gave him and he apologised for being so much trouble. He then dosed and wandered in his sleep, sometimes talking in Chinese and sometimes in English. At 1 a.m. he wanted to turn on his side. I helped him over and he thanked me and talked quite rationally. A few minutes later a sudden change took place and he became unconscious, and ten minutes later he passed away, quite peacefully - resting in my arms”.

“So died a brave soldier, a remarkable traveller, and a devout Christian”.

HGT’s diagnosis was that he had died from a perforated gastric ulcer.

Day ninety-six Saturday October 20th 1923 Kanze

“The Tibetans dispose of their dead either by throwing the body into the river or by putting it out to be eaten by vultures. Kanze has a population that is almost entirely Tibetan but the Chinese traders in Kanze have a small plot of ground. which they use as a cemetery and which is reserved for special Chinese burials. I visited the magistrate and got him to promise a site for burial in that cemetery. This was important because they keep a record of the graves, and there will then be no risk of the ground being desecrated by Tibetans. Everything is being arranged as well as possible. I knew that it would have been GP's wish to be buried there, because when one of the muleteers died on the journey he said - "Wherever I die I want to be buried, and not for my body to be conveyed to some other place". So, he will rest on the borders of Tibet, and yet just inside China - the one country to which he seemed drawn, and the other where he had spent so many years".

In his journal HGT wrote:

“This has come as a big blow not only to me, but also to his Chinese and Tibetan boys - who were very fond of him".

"A good man called to rest. When my turn comes, may my end be as peaceful as his was.”

Day ninety-seven Sunday October 21st 1923 Kanze

"The funeral took place at 4 p.m., the coffin was very heavy, and was carried to the grave by about 18 Tibetans - men and women helping. There had been 6 inches of snow on Friday night and 4 inches on Saturday - so the road was very slippery and in places about 8 inches deep in mud, for the sun was warm and the snow rapidly melting. GP was laid to rest there, under the shadow of the Great Kanze Lamasery and within sight of the great snow-range forming the Ho chu lung divide".

The funeral of Brig Gen Georfe Pereira CB, CMG, DSO outside Kanze

The funeral of Brig Gen Georfe Pereira CB, CMG, DSO outside Kanze

Resting place of Brig Gen George Pereira CB, CMG, DSO at Kanze

Resting place of Brig Gen George Pereira CB, CMG, DSO at Kanze

“There was no sign of reverence about the bearers - they were laughing and joking all the way. The two boys and I followed the coffin which was very heavy. The General's sword and military cap was placed on the coffin at the grave, I read those beautiful words, "I am the Resurrection and the life, etc., " Then the Chinese boy read part of 1 Corinthians 15 and after prayer they committed the body to the grave, and then waited to see the earth filled in. A temporary wooden cross was placed over the grave”.

“As there is a Roman Catholic priest two marches away, arrangements were made with him for a more permanent memorial. After the funeral I returned to our lodging place and began to get things in order. It seemed very strange without the General, and to be alone. After careful thought, I decided to continue the journey as we had planned it, aiming to cross part of the Golok (Note Now known as Ngolok) country and reach the Yellow River either along the southern part of the bend or at Sotsong Gomba, at the bend of the river. I called the boys and asked them if they were willing to work for me as they had the General, and they both agreed".

Whilst at Kanze they were visited by a senior lama – a living Buddah.

A living Buddah (senior lama) visiting them at Kanze

A living Buddah (senior lama) visiting them at Kanze

Living Buddha and his attendant Lamas

Living Buddha and his attendant Lamas

Day ninety-eight October 22nd, 1923. Kanze

“I have been busy all morning developing the films taken on the way between Batang and Kanze. I have got through 4 rolls and have two left to develop tomorrow. In addition, I am busy over the route question; having decided to carry on the Expedition as we are about half way through. According to the accounts of the merchants etc., the road to the Golok camp is absolutely blocked so I have decided to take another route - more to the East, which is quite peaceful - and passable.

Note (according to Wikipedia): The Golok or Ngolok peoples are groups from Kham and Amdo in eastern Tibet, where their territory is referred in Tibetan as “smar kog”. They are located around the upper reaches of the Yellow River and the sacred mountain Amne Machin. They are not a homogeneous group but are composed of peoples of very different geographic origins across the Khams and Amdo region. The Goloks were renowned in both Tibet and China as ferocious fighters. Legends say they were ruled by a queen, a reincarnated goddess whose power was handed down from mother to daughter .

“I have planned to follow the Ta Chien lu road to Tao Wu (4 days), then strike North, via Nun Chang, Su Chong Somo to a river called the Peh Ho - follow this for 4 days to the Yellow River - then strike N/W to the Heh River, and from there it is reported to be 8 days march to old Taochow (Tao Chow ting). A total journey from Kanze to Tao Chow of 32 days, and another 8 days on to Lanchow. 40 days in total”. This is going slowly each day, or going a little quicker and allowing 1 day a week for rest. The local merchants have an arrangement to assist their caravans through, and I was fortunate in getting 2 of the merchants to help him. They would send one of their men who knew the route to act as guide and help to make arrangements".

"I reckon that dates should now be something as follows:"

Leave Kanze October 25th

Arrive Tao-chow November 24th

Leave Tao-chow November 26th

Arrive Lanchow December 5th

Leave Lanchow December 8th

"By the new route we ought to arrive at Lanchow at least 12 days earlier than according to the plan despatched from Batang".

"Aim to arrive Peking - date uncertain, - probably early January – will wire this from Lanchow. The mail out from this place (Kanze) is very Irregular. One left on the day we arrived, and they say there is no other due to leave a week to 8 days since the last despatch."

“I will wire this from Lanchow. The mail out from this place (Kanze) is very irregular. One left on the day we arrived, and they say there is no other due to leave a week to 8 days since the last despatch”. “Travelling by this new route I hope to arrive at Lanchow at least 12 days earlier than we had planned when leaving Batang”.

Day ninety-nine October 24th, 1923. Kanze

HGT wrote in his letter home:

“All is fixed up and we leave tomorrow morning. We have put a wooden cross on Pereira’s grave – with an inscription – This is of course temporary until we see what his relations wish – but I have written to Sir Cecil Pereira with full details and sent duplicated copies by different routes, so I feel I have done all I can.

The magistrate here has been most kind. Incidentally I have had him as a patient.

Now I must send this to the mail.

Yours,

H.G.T.”

Copyright © 2021 John Hague. All Rights Reserved

Special thanks to Mr Edward Pereira, great nephew of Brig. Gen. George Pereira for providing me with copies of his great uncle's journal.

References:

The Geographical Journal Vol. LXVII No. I

The Royal Geographical Society January 1926 Published by Edward Stanford 1926

Peking to Lhasa by Sir Francis Younghusband.

The Narrative of Journeys in the Chinese Empire Made by the Late George Pereira . Compiled by Sir Francis Younghusband from Notes and Diaries.

Published by Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1926

The Illustrated London News

No 4528 Vol 168 published on 30th Jan 1926

and

No 4529 Vol 168 published on 6th Feb 1926